Fatalities, Work Accidents, Union Suppression and Worker Criminalization: The Fate of Indonesian and Chinese Workers at the PT GNI Nickel Smelter #1

By Permata Adinda and Muammar Fikrie for Project Multatuli, May 26, 2023

SEEING HER 23-YEAR-OLD SON behind bars, separated by a small room, Mulyati couldn’t hold back the tears. On the visit the mother and son were prevented from touching. They also had to raise their voices to speak with each other.

That day the North Morowali District police station experienced a power outage that stops the police from printing visitors permits. “Please just wait, miss. The lights haven’t come on yet,” a policeman told Mulyati.

It was nearly 10.00 a.m.. If they waited any longer Mulyati worried she wouldn’t get a chance to visit Jumardin. Usually the visiting queue grew longer as the day progressed.

“Rather than waiting too long,” said Mulyati, who usually saw her son outside the holding cell.

In the cell, Umar, Jumardin’s nickname, held onto the bars. He remained silent, looking at his 40-year-old mother in tears.

“I hope I’m not in here for Ramadan,” Umar said, when asked about his activities while being detained in the cell.

Mulyati recounted how difficult it was to visit. It took her about 30 minutes to get to the police station from her home. Usually she and Umar’s younger sister rode a motorcycle borrowed from the village chief’s father. But that day the motorcycle had a flat tire. They had to find another ride.

Mulyati brought some packed meals for Umar and his friends in the detention cell. Umar often asked for rice. The portion of rice provided in the detention cell was small, and the side dishes were meager. “He says the food in there is—,” but Mulyati starts to choke up. “Just to fill him up. He always asks for rice. Real rice!”

Exactly 12 minutes after Jumardin’s name was called, a police officer approached Mulyati and told her her visiting time was up.

Mulyati said her goodbyes. She told Umar to behave in the cell.

“Hopefully you’ll be out before Ramadan. Ask to be released, okay. Who knows, maybe you’ll be free by then,” Mulyati said. Umar nodded.

Jumardin, Smelter Division Worker

On January 14, 2023, Jumardin bid farewell to go for his night shift at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (PT GNI). He has never returned.

Usually, Umar would be back home by 9 in the morning the next day. He would always let his family know if he wouldn’t be home early, or if he planned to stay overnight at a friend’s place. However, by 11 in the morning on the following day, Umar hadn’t communicated with anyone.

Mulyati grew anxious. She asked Umar’s younger sibling to call him, but they received no response.

Towards noon, a relative came to the house with news. Umar, the main provider for the family, was at the police station. Mulyati fainted.

Umar, born in 2000, was the only child of four siblings to graduate from vocational school. His three siblings only completed junior high school. His family considered Umar the hardest working and the most intelligent. They pinned their hopes on him.

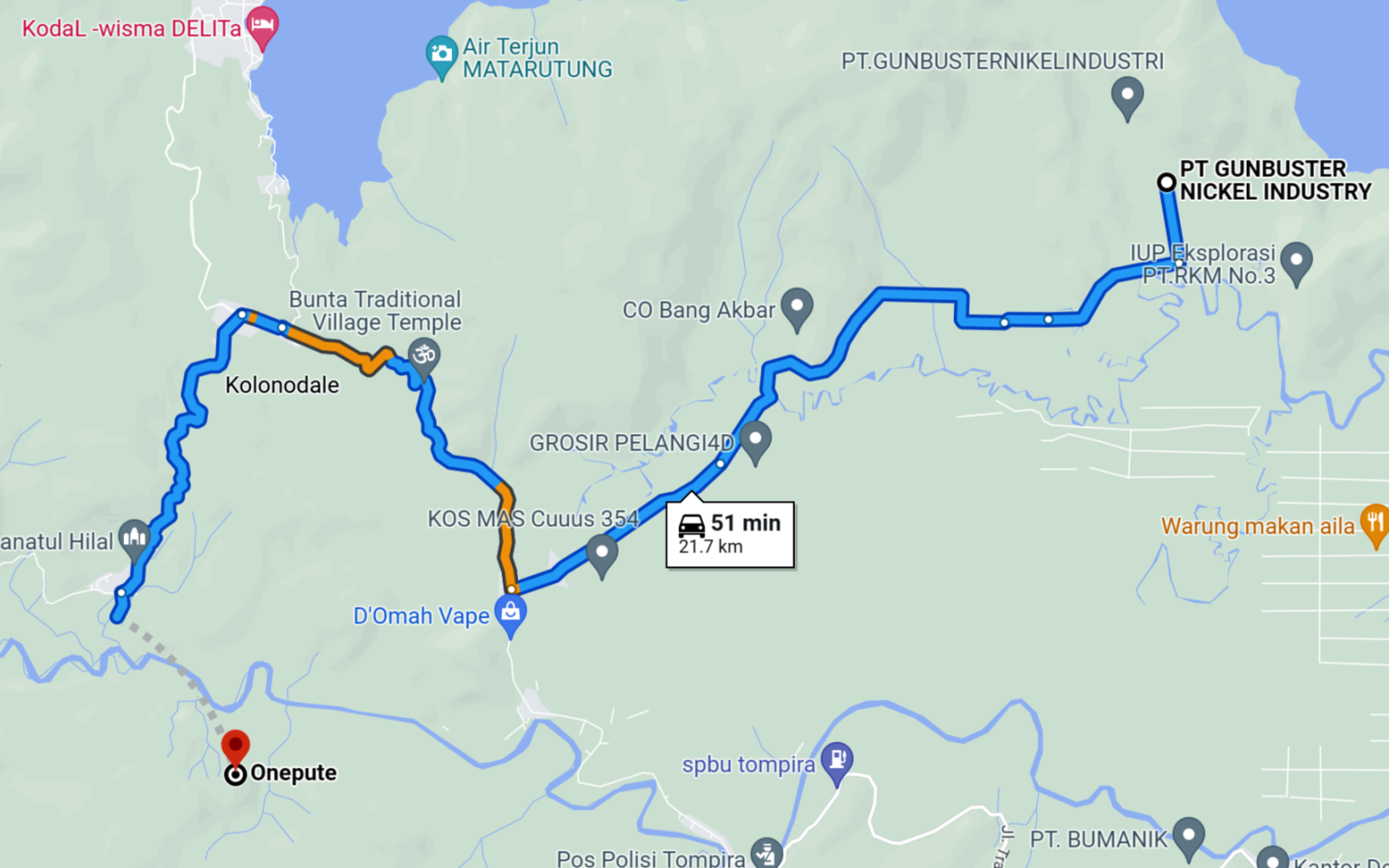

The family lives in Onepute Kampong, West Petasia Sub-district. Umar’s father, aged 60, has been unwell. He used to work as a motorcycle taxi driver, shuttling back and forth to Kolonodale, the capital of North Morowali Regency, 8 miles from the village. With time he became unable to work. His health deteriorated, and he frequently suffered from back pain.

Umar took over. After completing vocational school, he did whatever work he could find. He helped support his parents, three siblings, and a nephew.

Three years into odd jobs, Umar found out about a job opening at PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (PT GNI). Many young men from his village applied, and Umar joined them. He was accepted to work in the smelter department. His salary was Rp3,150,000 ($210)/month, plus meal and overtime allowances.

Now with no income from Umar, this family struggles to meet its daily needs.

Sometimes sympathetic neighbors send food. Occasionally Mulyati washes clothes or cooks for other families, earning Rp20-25,000($2 to $3).

Since Umar’s arrest, two installments have been missed for the motorcycle and cellphone. The motorcycle installment is Rp2.2 million($147)/month. The cellphone installment is Rp500 thousand($33)/month. Umar paid both to make work easier.

Last April, Umar’s family ran out of ways to pay for the loans. Someone else might be able to take over the motorcycle installments, but the cellphone needed to be returned. The problem is, Umar’s phone is still seized by the police. The police claim it is still “evidence”. Meanwhile, the phone shop keeps demanding payment from his family or the return of the phone.

“I’ve called the investigator,” said Yulan, Umar’s sister. “The investigator said the phone would be returned. But he said there’s still something to be analyzed on the phone. If there’s any data to be retrieved, retrieve it. But please return the phone.”

Umar’s family is the only one regularly visiting the North Morowali police station, where nickel smelter workers are detained. This family is of Bugis descent, but has long settled in North Morowali, and even speaks Mori fluently, the native language of North Morowali, making them more comfortable being referred to as native Mori.

Meanwhile, the other detainees are newcomers. Most are from South Sulawesi; from Palopo, Pinrang, or Makassar. Their families cannot afford to travel back and forth to North Morowali given the money, energy, and time involved.

Mulyati and her daughter once took Bilal, Yulan’s 5-year-old son, to visit Umar. Umar used to play with his nephew and tease him. When Umar returned from work late at night, he would wake Bilal up. Bilal missed Umar. He often asked his mother when his uncle was coming home.

“When Bilal visited, Umar didn’t want his nephew to see him. He asked to be taken outside. Umar couldn’t bear to see him,” Yulan recounted. “Meanwhile, Bilal was searching for his uncle for a long time as he had never been at home.”

“For me… for me I can’t visit Umar. It’s just… my heart isn’t ready. It’s still too painful,” Yulan said.

Bilal sat beside his mother. He had just returned from Quran-reading lessons.

“Where’s uncle?” asked Bilal.

“In jail.”

UMAR’S DAYS IN CONFINEMENT in the police cell were filled with uncertainty. His family waited for answers. How long would their child be detained at the police station? When would Umar come home? When would Umar be released?

At first the family was told that Umar would only be detained for 1 or 2 days. “We were just given that information to calm us down,” said Mulyati.

However, after two nights news came from Jakarta. National Police Chief Listyo Sigit Prabowo announced that 17 individuals had been named as suspects, including Umar. That night, the workers were transferred to the holding cells at North Morowali district police headquarters.

The Head of Public Relations of the Central Sulawesi Regional Police, Didik Supranoto, stated that investigators had charged 16 suspects with assault, punishable by up to 5 years in prison. Another worker had been charged with arson, carrying a penalty of up to 12 years in prison.

However, Umar’s family did not understand or know this information. When we met Umar’s family in March 2023, all they were trying to obtain was some certainty about when Umar could be released from custody.

In his work, Umar wasn’t one to complain easily. He rarely talked about his work situation with his family. Before aquiring his own motorcycle, Umar used to hitch rides with fellow workers to and from PT Gunbuster Nickel Industry (GNI). The distance from Onepute Kampong to the entrance of PT GNI is about 16.5 miles, or a one-hour journey by motorcycle.

“Sometimes if the friend he rides with didn’t go, he would be stuck too. So his father said, ‘Just buy a motorcycle. After all you’re the one looking for work. You can cover the cost yourself,’” Yulan recounted.

Umar only mentioned briefly that working in the smelter department was often unsafe. Because they weren’t provided with adequate personal protective equipment. When he started working, Umar wasn’t given anything except a helmet. He was only given safety shoes several months into the job. (Continued..)

This article is based on https://projectmultatuli.org/kematian-kecelakaan-kerja-pemberangusan-serikat-kriminalisasi-nasib-pekerja-indonesia-dan-tiongkok-di-industri-smelter-nikel-pt-gni/.

Featured image credit: Tropical Rainforest in Indonesia By Rhett Ayers Butler https://www.butlernature.com/2022/01/04/whats-the-outlook-for-tropical-rainforests-in-2022/

In related news:

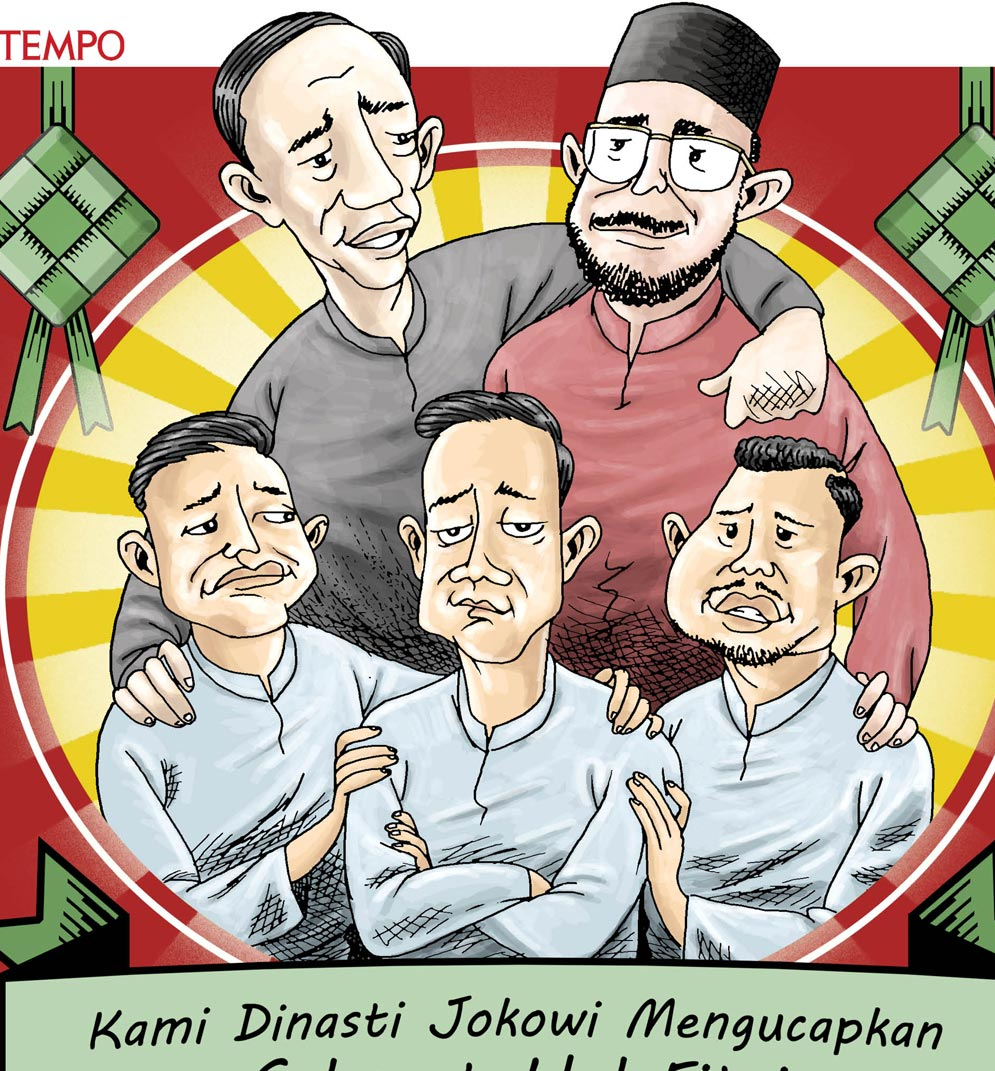

- Profile of PT GNI in North Morowali where 2 workers died during clashes

- https://www.kompas.com/tag/bentrok-pekerja?page=2

- https://www.tempo.co/search?q=GNI

- https://bisnis.tempo.co/read/1814128/perusahaan-smelter-nikel-dari-cina-ini-profil-pt-tiss-morowali-dan-pt-gni

- https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1815466/dua-kebakaran-tungku-smelter-dalam-sepekan-di-morowali-kronologi-kejadian-di-pt-itss-dan-pt-gni

- https://go.kompas.com/read/2023/01/17/093724774/riot-at-chinese-funded-nickel-plant-in-indonesia-kills-two

- https://bisnis.tempo.co/read/1460228/kembangkan-smelter-nikel-antam-gandeng-alchemist-metal-gunbuster-nickel and https://storiesfromindonesia.com/2024/02/08/elections-china-downstream-the-tentacles-of-indonesias-nickel-oligarchy-by-project-multatuli-part-3/

- https://www.thejakartapost.com/business/2021/12/29/china-backed-3b-nickel-smelter-starts-up-in-morowali.html

- https://news.metal.com/newscontent/101726334/the-third-phase-of-delong-industrial-park-in-indonesia-has-been-signed

- https://thediplomat.com/2023/01/chinese-and-indonesian-workers-clash-at-indonesian-nickel-plant/

- https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20221229122014-4-401135/pabrik-nikel-di-morowali-kebakaran-pemiliknya-asal-china

- https://money.kompas.com/read/2023/10/02/153100126/ciptakan-lingkungan-kerja-harmonis-pt-gunbuster-nickel-industry-gelar-seminar?page=all

- https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN2J60NW/

Leave a Reply