Is the Press in Southeast Asia in Danger?

By Permata Adinda, from Asumsi.co, March 21, 2021

Repression is being experienced by journalists from Al Jazeera in Malaysia to Rappler in the Philippines.

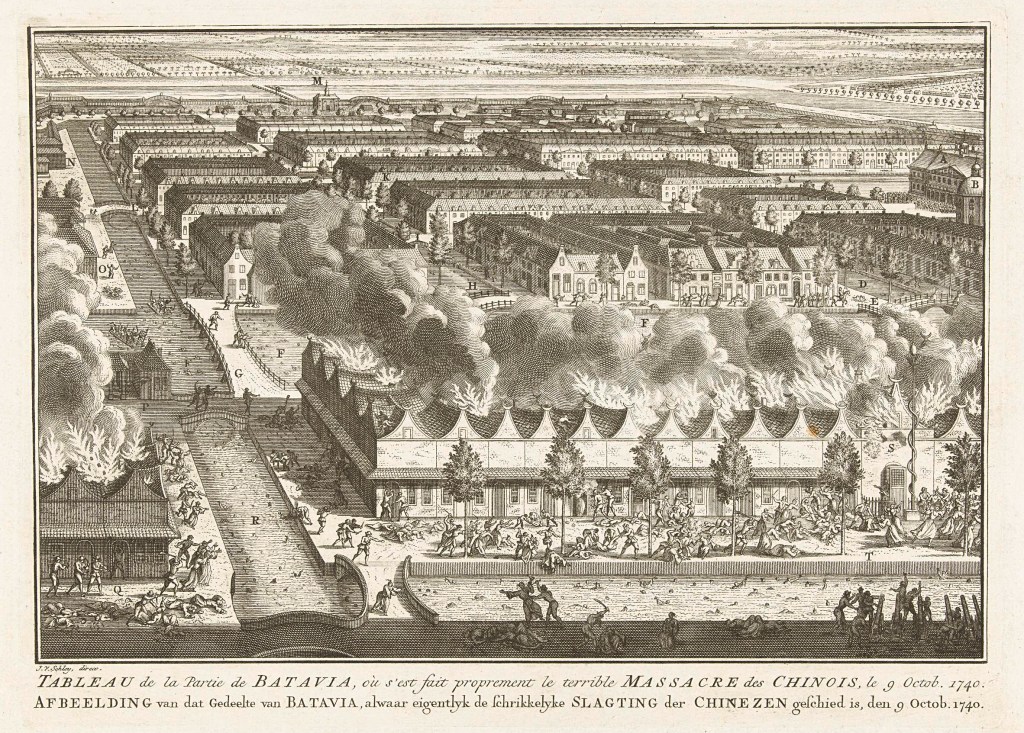

Al Jazeera’s office in Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, was raided and two computers seized by police (4/8) after the media screened a documentary highlighting the Malaysian authorities’ arrests and inhuman treatment of migrants during the pandemic.

Authorities condemned the film, judging it to be inaccurate, unfair and misleading. Malaysia’s Minister of Communications and Multimedia, Saifuddin Abdullah, said the film did not have a shooting permit which according to Al Jazeera did not require permission because it was included in the category of latest news which was always aired every week.

This documentary entitled Locked Up in Malaysia’s Lockdown is part of the 101 East Al Jazeera program. After the film was released, the editorial team members and the subjects interviewed in the film received many death threats, violence, and doxing of their personal data on social media.

One of the informants from Bangladesh, Mohamad Rayhan Kabir, was arrested on 24 July. Authorities said he would be deported and barred from entering Malaysia forever.

Responding to the repressive attitude of the government, Al Jazeera condemned the action, viewing it as an attack on press freedom. These raids are seen as a “disturbing escalation” of violent behavior by the authorities against the media, demonstrating the extent to which they can intimidate journalists.

“Al Jazeera sided with journalists and our coverage. Our staff did their job and they did nothing wrong to make them need to apologize or clarify. Journalism is not a crime,” said Al Jazeera managing editor Giles Trendle.

There has also been criticism from Amnesty International Malaysia which is urging Malaysian authorities to stop harassing Al Jazeera and to halt investigations against staff and media reporters. “Violence by the government against migrants, refugees and anyone who defends them is clearly an attempt at silencing and intimidation that must be condemned. Protect migrants. Protect freedom of expression.”

Press freedom in Southeast Asia has indeed been worrying in recent years. Reporters Without Borders reports in 2020 showed media freedom scores in all Southeast Asian countries had decreased compared to the previous year, with an average ranking of 138 out of 180 countries. Another report by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and Southeast Asia Journalist Unions (SEAJU) found that 61% of press workers in the region felt their jobs were unsafe, a figure that has increased by 11% from the previous year.

Prior to this journalist Tashny Sukumaran from the South China Morning Post in Malaysia also experienced criminalization and repressive behavior. Having also reported on the detention of refugees and illegal migrants in the red zone of COVID-19 in Malaysia, he was arrested on charges of “committing insults with the intention of provoking and destroying the peace” and was sentenced to a maximum of two years in prison.

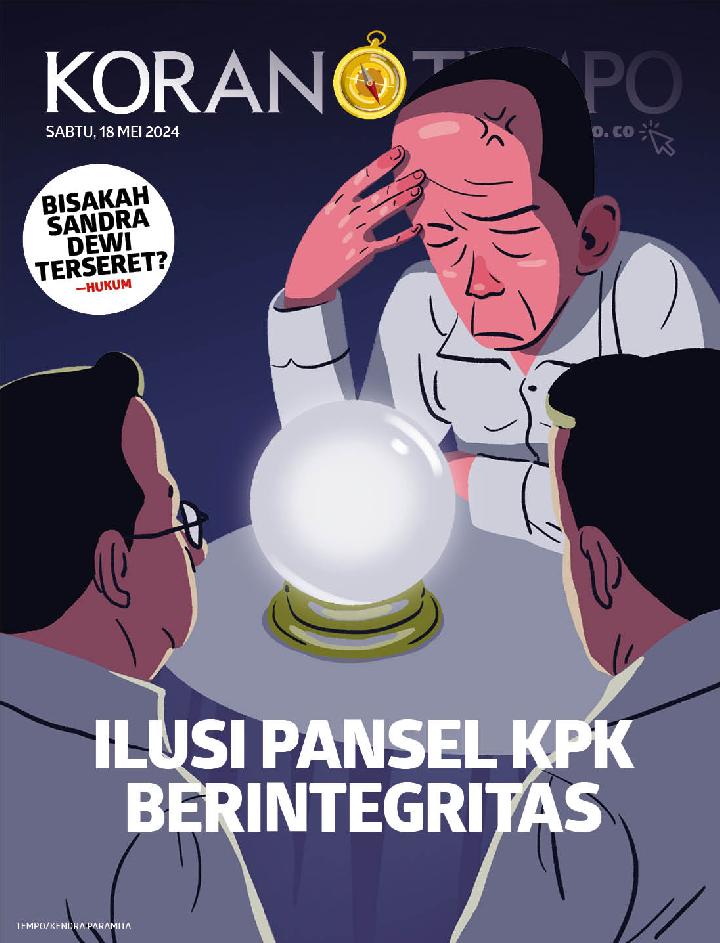

Apart from Malaysia, journalist and CEO of Rappler Maria Ressa in the Philippines was also found guilty of “cyber slander” for her articles on drug and human trafficking cases involving the chairman of the Supreme Court and a number of business people. Ressa was also ordered to pay a fine of P400,000, or equivalent to Rp. 119 million. There have also been the detention of Reuters journalists in Myanmar, the closure of several media companies in Malaysia and Cambodia, and the increasing censorship of news in Thailand.

This repressive behavior towards journalists also often acts on the pretext of “the need to fight misinformation”, and the COVID-19 pandemic has become an arena to strengthen the power of authority over the press. The Thai Prime Minister threatened to suspend or edit news deemed “untrue”. These governments also have the right to correct information which they think is problematic.

Singapore’s Protection Against Falsehood and Online Manipulation Act empowers the government to correct or release news stories. This occurred in the State Times Review after the media accused the government of covering up cases of COVID-19. Likewise, the Cambodian government has the power to prohibit the dissemination of information deemed to cause “riots, fear or chaos.”

“Journalism is a very dangerous profession today,” said Maria Ressa at Time.com. “But this profession is more important than ever. We have to survive or we will lose a lot. “