China Downstream: The Tentacles of Indonesia’s Nickel Oligarchy

By Project Multatuli & Viriya Singgih, February 2, 2024

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

“Downstreaming” (or hilirisasi) has been a key catchphrase over the 10-year tenure of Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo. Not only is the term linguistically contrived, but its associated policies often present an illusion of progress that could potentially backfire.

When President Joko Widodo was officially inaugurated in October 2014, he inherited former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s policy of banning the export of raw minerals, including nickel ore and bauxite, starting at the beginning of that year, aimed at boosting domestic processing industries.

Nearly 10 years later, after repeatedly wavering between enforcing the ban and various “relaxations” (another frequently-uttered jargon used by officials), the Widodo administration claims that nickel is a successful example of downstreaming, purportedly propelling Indonesia to “leap” into the status of a developed nation.

Nickel raw materials can be processed into various commodities, including coins, wire, stainless steel, and electric vehicle batteries. Considering the global trend towards using electric vehicles, and the pressure to reduce carbon emissions, the Widodo administration has opened doors wide for investment in order to develop domestic nickel mining and processing operations, especially given Indonesia’s abundant nickel reserves.

Nickel Reserves

The calculation of nickel resources and reserves is divided into two: ore and metal. The total nickel ore resources in Indonesia (is estimated to) reach 17.3 billion tons, with metal estimates up to 174.2 million tons, according to government data as of 2022.

At the same time, based on information from the United States Geological Survey (USGS), Indonesia’s proven nickel metal reserves reach 21 million tons, the largest in the world, alongside Australia. Both countries (together) hold 21% of global nickel reserves.

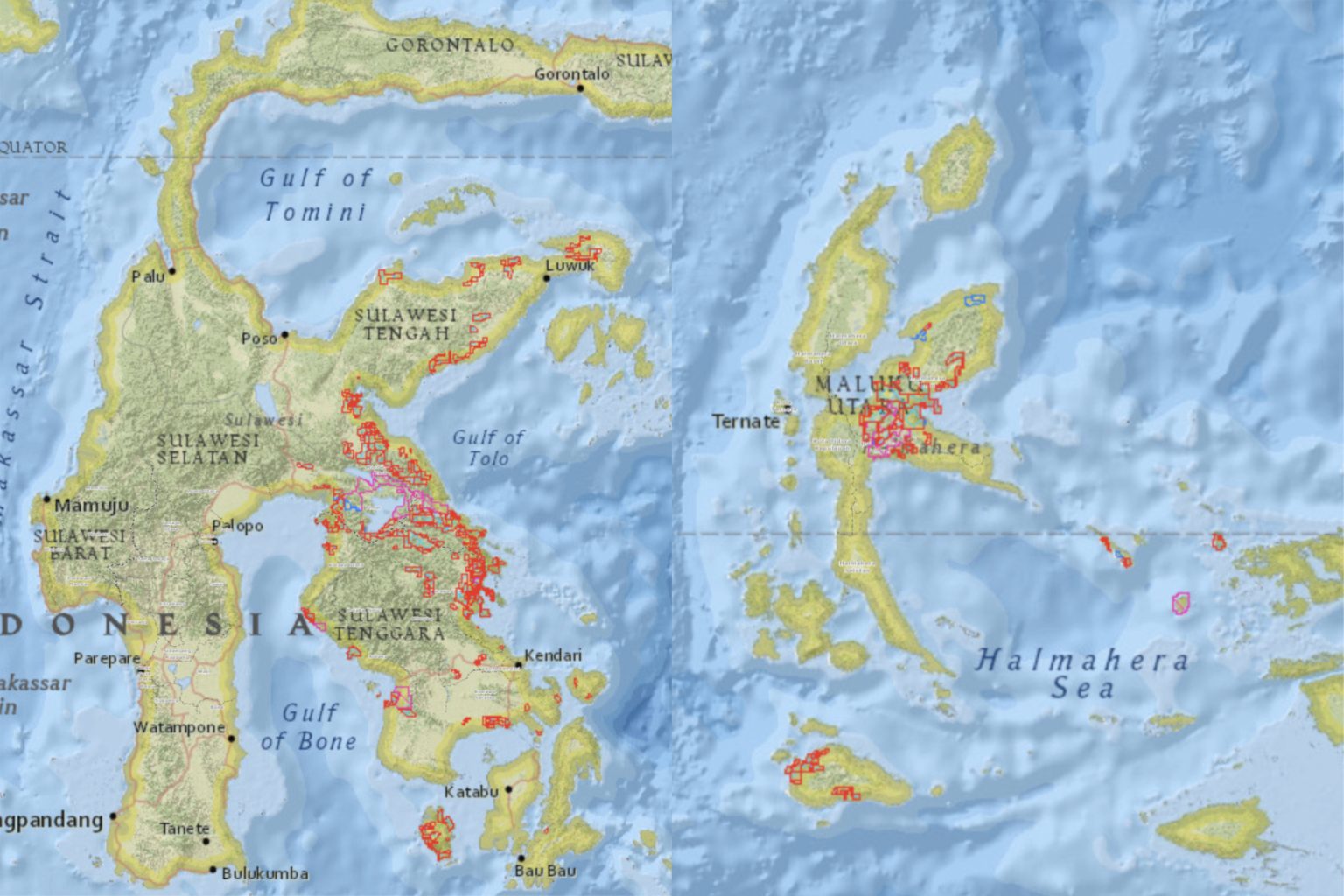

Indonesia’s nickel supply is concentrated on Sulawesi Island, with proven reserves reaching 54.7% of the total Indonesian figure. The second-largest nickel reserve repository is the Maluku Islands with 44.6%.

Observing this, investors, whether foreign or local, have flocked to these regions to mine or establish a variety of nickel processing plants.

As of 2023, there were 373 nickel mining concessions with clean and clear (CnC) status issued by the Indonesian Government, either in the form of Mining Business Licenses, or Contracts of Work. This encompasses an area totaling 960,117 hectares. Of these, 309, covering 691,929.6 hectares, are located in South, Southeast, and Central Sulawesi. Then, there are 59 concessions in North Maluku, and only one in Maluku, with a combined area of 231,486.4 hectares.

From hundreds of these data points, Project Multatuli has scrutinized four corporations, or business groups, controlling CnC concessions totaling 271,650.5 hectares, or more than 28% of Indonesia’s nickel mining land. They are PT Vale Indonesia, PT Aneka Tambang, PT Weda Bay Nickel, and the Bintangdelapan Group.

Long History

Aside from controlling massive land areas, they represent different interests, and chapters in Indonesia’s long history of nickel mining.

PT Aneka Tambang initially was the Public Management Authority of State Mining Companies (BPU Pertambun), tasked with managing all government mining companies and projects outside the oil and gas, coal, and tin sectors during President Sukarno’s first term.

PT Vale Indonesia was the second foreign investment company to enter Indonesia after PT Freeport Indonesia. It signed a Generation II Contract of Work with the government in 1968, during the authoritarian presidency of Soeharto, who vigorously attracted foreign investment to the domestic mining sector.

PT Weda Bay Nickel is the company that signed a Generation VII Contract of Work before the collapse of the Soeharto regime in May 1998 and, through various changes and policy ambiguities, whether related to mining in forest areas, or bans on raw mineral exports.

Belt and Road Initiative

The Bintangdelapan Group is a local private company that paved the way for a flood of investment, primarily from China, into Indonesia since starting to collaborate with the giant stainless steel producer Tsingshan Holding Group since October 2013. This collaboration is part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) launched just a month earlier.

The BRI aims to build an “economic belt,” or land trade routes, connecting China with various regions in Southeast Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, and Europe, as well as “maritime routes,” or sea trade routes, from coastal China to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the South Pacific region, the Middle East, East Africa, and Europe.

Through the BRI, China spreads its influence by pouring vast sums of money into infrastructure development in various countries, including for the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Train, dams, power plants, and nickel processing plants in Indonesia.

Some observers view this move as China securing political support from economically vulnerable countries in the Asia-Pacific through project debt entanglements.

As a result, Chinese and Hong Kong investments in Indonesia continue to soar. From just $1.46 billion in 2014, it peaked at $13.7 billion in 2022, before dropping to $10.8 billion a year later. Initially, China and Hong Kong only contributed 5.1% to the total foreign direct investment figure. Over a decade, their share reached 28.6%.

As a side note, Hong Kong serves as a gateway for various Chinese companies to invest overseas. Many Chinese subsidiaries there, for example, are used as vehicles to manage nickel smelter projects in Indonesia.

Initially, what was predominantly built in Indonesia were rotary kiln-electric furnace (RKEF) technology smelters to process nickel ore through heat and pressure into low-grade ferro-nickel, or nickel pig iron (NPI), which can be used as a material for stainless steel production.

EV Batteries

Later, high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) technology plants emerged, using sulfuric acid to separate nickel and cobalt compounds from laterite nickel ore. The result is a mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP) that can be further processed to make electric vehicle batteries.

There were 116 nickel smelter projects in Indonesia in 2023, including those that were operational, under construction, and in planning. Ninety-seven of them are RKEF smelters, and the remaining 19 use HPAL technology. For comparison, there were only 31 projects in 2014.

As a consequence, the need for nickel ore to be processed by the 47 operational smelters in 2023 alone reached 233.5 million tons, although at that time Indonesia’s total nickel production was only 193 million tons. Therefore, the government plans to implement a moratorium on new nickel smelter construction, especially those using RKEF technology, to maintain the supply’s lifespan.

However, the issue stemming from the proliferation of nickel mines and smelters is not just about supply. Nickel mining operations in Indonesia are said to have caused deforestation covering 78,948 hectares since 2014.

Power plant operations in the Morowali Industrial Zone in Central Sulawesi and the Weda Bay Industrial Zone in North Maluku, for example, have polluted the air, and led to spikes in cases of acute respiratory infections. Not to mention land clearance issues that have triggered horizontal social conflict, and even led to smelters being built on indigenous land.

Capital Intensive

Moreover, investments in the processing sector are capital-intensive, not labor-intensive. Typically, many workers are only needed during the initial stage of infrastructure construction. Afterwards, machines take over. Throughout 2017-2022, the poverty rate in Southeast Sulawesi, for example, remained higher than the national average.

Who truly benefits from “downstreaming”?

We delve into the history, ownership structure, and business networks of four nickel mining giants with the largest concessions in Indonesia. The information and data used come from various sources, including the limited company database of the Ministry of Law and Human Rights, the “Minerba One Data Indonesia”, and “Minerba One Map Indonesia” portals managed by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, annual and financial reports of various mining companies, research by civil society organizations, court archives, news articles, and other sources.

From this research, it is apparent that Chinese investment in the downstream nickel industry is indeed dominant. Nevertheless, local entrepreneurs are slowly emerging from the sidelines through business groups such as Adaro, Aserra, Bintang Delapan, Harita, Jhonlin, Kalla, Merdeka Copper, Rimau, and Saratoga.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5

(This article is based on https://projectmultatuli.org/cina-di-hilir-gurita-oligarki-nikel-indonesia/.)

In related news:

Leave a Reply