Reassessing Civil-Military Relations in Indonesia

By Ikhsan Yosarie for Koran Tempo, May 9, 2024

Placing military personnel in civilian roles risks undermining efforts to reform the Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI). Civil-military relations remain less than ideal.

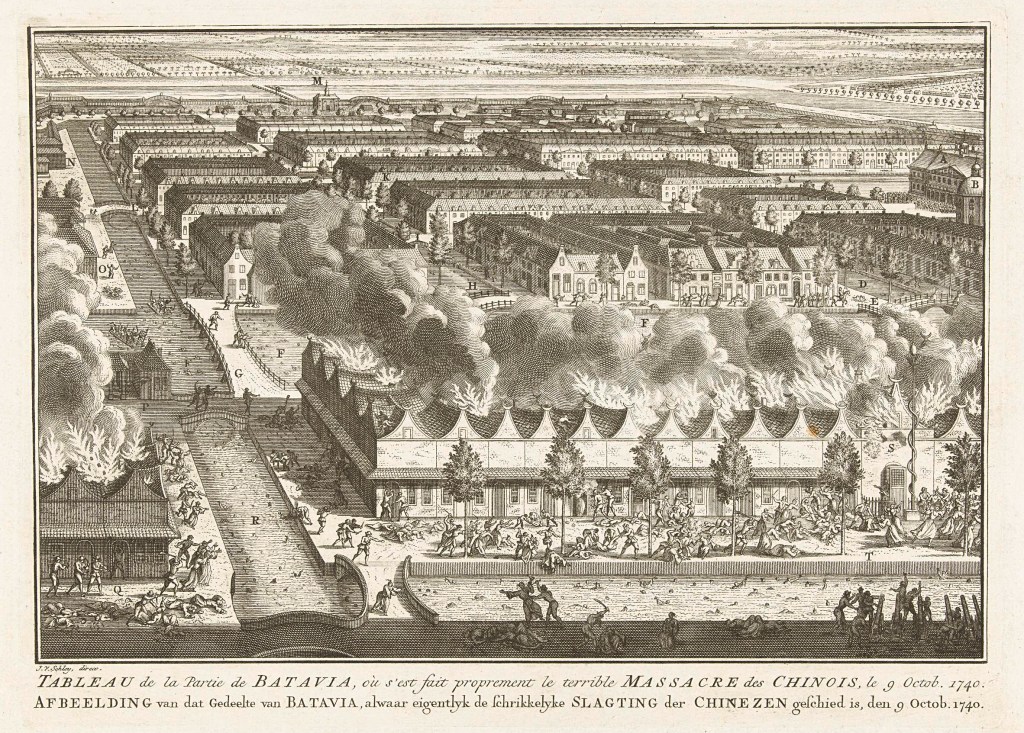

Civil-military relations represent a key topic in studies of the military and politics, particularly within Indonesia. The experience of the New Order era serves as a significant marker for the assessment of these dynamics. Not only did the military bolster the regime’s authoritarianism, but the adverse effects of less-than-ideal civil-military relations at the time led to the transformation of the military (the Indonesian Armed Forces, or ABRI, as it was known at the time) from an instrument of the state into a tool of partisan political power.

Recent discussions on achieving ideal civil-military relations have gained relevance. The urgency extends beyond the reform of TNI to the broader benefits to be gained through strengthening the democratic climate.

This topic has gained increased attention because of recent proposals to expand the number of military personnel placed in civilian roles through the recently released draft Government Regulation on State Civil Service Management (RPP Manajemen ASN). Additionally, social media has recently been in overdrive with video clips depicting violence in Papua involving military personnel.

The urgency to revisit civil-military relations stems from the perspective of Michael C. Desch (2002). He explains that most people view civil-military relations solely through the lens of coup events. Essentially, if a military coup occurs, civil-military relations are deemed poor. Conversely, if there’s no coups, relations are considered good.

However, Desch argues that a country can have poor civil-military relations even without the threat of coups. This sentiment was echoed by Samuel Huntington (1985). In the context of civil-military relations, the issue in modern nations isn’t armed rebellion, but rather the relationship between the military and politicians.

Understanding Civil-Military Relations

There is an extensive literature available for understanding civil-military relations, both in relation to the sociopolitical realities of Indonesia and more conceptually. One such study is by Yuddy Chrisnandi (2004), which delves into the state of civil-military relations during the early days of the democratic reform period after 1998 (Reformasi).

In his dissertation, Yuddy explains that civil-military relations in the early Reform days didn’t yet indicate the presence of full civilian control over the military. This is understandable given the transitional democratic struggles related to ABRI’s so-called dual defense and political function (dwifungsi). The question of whether its implementation should be corrected, gradually phased out, or entirely abolished lingered.

Conceptually, Huntington (1985) adeptly explains the typology of civil-military relations. He identifies two forms: objective civilian control, and subjective civilian control. These two forms are diametrically opposed and have different impacts.

While objective control seeks to strengthen military professionalism, subjective control aims to assert dominance over the military for specific purposes. Subjective control is associated with the particular interests of one or more civilian groups, and involves power relations among these groups.

Another impact of implementing this typology is civilian militarization or militaryization as it places some object beyond its defense role and function, narrowly cast. Various historical manifestations of this condition can be seen during the 32 years of the New Order era between 1965 and 1998.

Meanwhile, Desch (2002), as in his initial thoughts, details the factors that shape or influence civil-military relations. He posits that five factors influence these relations: threats, leadership, military organization, state structure, and society.

Through the lens of civil-military relations, several questions arise: does the placement of the military members in civilian roles, and violence involving military members, depict objective control? Has this issue reflected good civil-military relations? Both questions have rather disappointing answers. Consequently, efforts for military reform must persist.

Normalization of Violations

In public discourse on expanding the number of military officers filling greater numbers of civilian roles, or incidents of military violence, the phenomena of normalization and defense has emerged. Normalization has taken the form, first, of a stream of thought that views positively the discourse on military placements in civilian roles, because it is believed to enhance public service performance.

At the same time, this argument arises without reference to the TNI Law or military reform. Indeed, such thoughts are translated into simple questions like “what’s wrong with it?” and “where’s the violation?” The public’s limited understanding of military reform ultimately impacts the lack of public awareness for the purpose of oversight of efforts at TNI reform.

Furthermore, in the violence incidents in Papua, public criticism of human rights violations leads to another controversy. Strong criticism of the military, such as that voiced by the executive board of the University of Indonesia Student Senate (BEM UI), has elicited negative responses ranging from ridicule and condemnation, to accusations that students are siding with the so-called “armed criminal groups” in Papua.

Yet, the essence of their statement has merely been a rejection of state violence practices. Such violence blatantly violates the human rights guaranteed by the Indonesia’s constitution and by international conventions. The University of Indonesia Student Senate has merely pointed out that cases of violence are not unprecedented, including those allegedly involving state agencies, and through should prompt thorough investigation.

The negative response to the students’ criticisms is a saddening phenomenon. It shows that some elements in society side with and defend violent actions. Those who deride the student criticism compare it to previous incidents of violence perpetrated by the groups in Papua labeled by the state as “armed criminal groups”.

False logic

That’s clearly a fallacy in thinking. Comparing acts of violence doesn’t negate the principle that such violence violates human rights, regardless of the actors and victims involved. This universal norm should serve as a guiding principle, so rather than seeking defense, the public should discuss efforts to protect victims, prevent such things happening, and advance measures promoting human security in the future.

Shallow emotional thinking

Challenging students to undertake community service projects in Papua reflects shallow thinking, prioritizing emotion over rational analysis—if we want to avoid calling it childish—when addressing an issue.

If the aim of such challenges is to help students address problems or mitigate conflicts in Papua, then the suggestion is clearly misdirected. These ideas devoid of substance reflect a lack of understanding among some segments of society regarding the distinctions between roles and functions, the purpose of criticism, and what constitutes evaluation.

Disadvantages for both side

From these various phenomena, it’s evident that the typology of civil-military relations in Indonesia hasn’t fully transitioned to objective civilian control. The practice of civil-military fusion or militarizing civilian functions still holds significant potential for realization through the proposed Government Regulation on State Civil Apparatus Management (RPP Manajemen ASN). The risks are apparent; for military personnel assuming civilian roles, their professionalism and understanding of combat may shift towards bureaucratic issues, which may not align with their capabilities.

Meanwhile, for civilian institutions, a number of risks also arise. Firstly, due to leadership influenced by a militaristic mindset, civil policies adopted may lack adequate evaluation mechanisms. Secondly, as a result of military influence, public policies adopted may risk contradicting efforts towards TNI reform.

Consequently, various policies that do not support military reform may become institutionalized, despite being heavily criticized by the public. Ultimately, the public may come to accept, and even support, a range of policies or practices that run counter to efforts to reform TNI.

This article is based on https://koran.tempo.co/read/opini/488376/hubungan-sipil-militer-di-indonesia.

In earlier reporting…

The Dual Function Agenda Behind Changes to Defense Force Law

By Hendrik Yaputra for Tempo.co, May 11, 2023

JAKARTA – Chair of the Initiative Center—a non-governmental organization focusing on democracy issues—Mr. Al Araf views the plan to increase active-duty officers’ opportunities to hold civilian positions through a revision of the Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI) Law as questionable. The agenda is seen as opening the door for the return of the dual function of the (formally named) Republic of Indonesia Armed Forces (ABRI) that existed during the three-decade rule of the New Order government (1965 to 1998).

Mr. Al Araf pointed out that the substance of ABRI’s dual function involved military involvement in practical civilian politics, aside from handling national defense affairs. Military involvement in practical politics took the form of ABRI officers occupying civilian positions, whether in ministries or state institutions, the House of Representatives, or regional heads. “This, of course, would mark a regression in the course of the 1998 reform movement and the process of democratization in Indonesia, which has positioned the military as a tool for national defense,” he said on Wednesday, May 10, 2023.

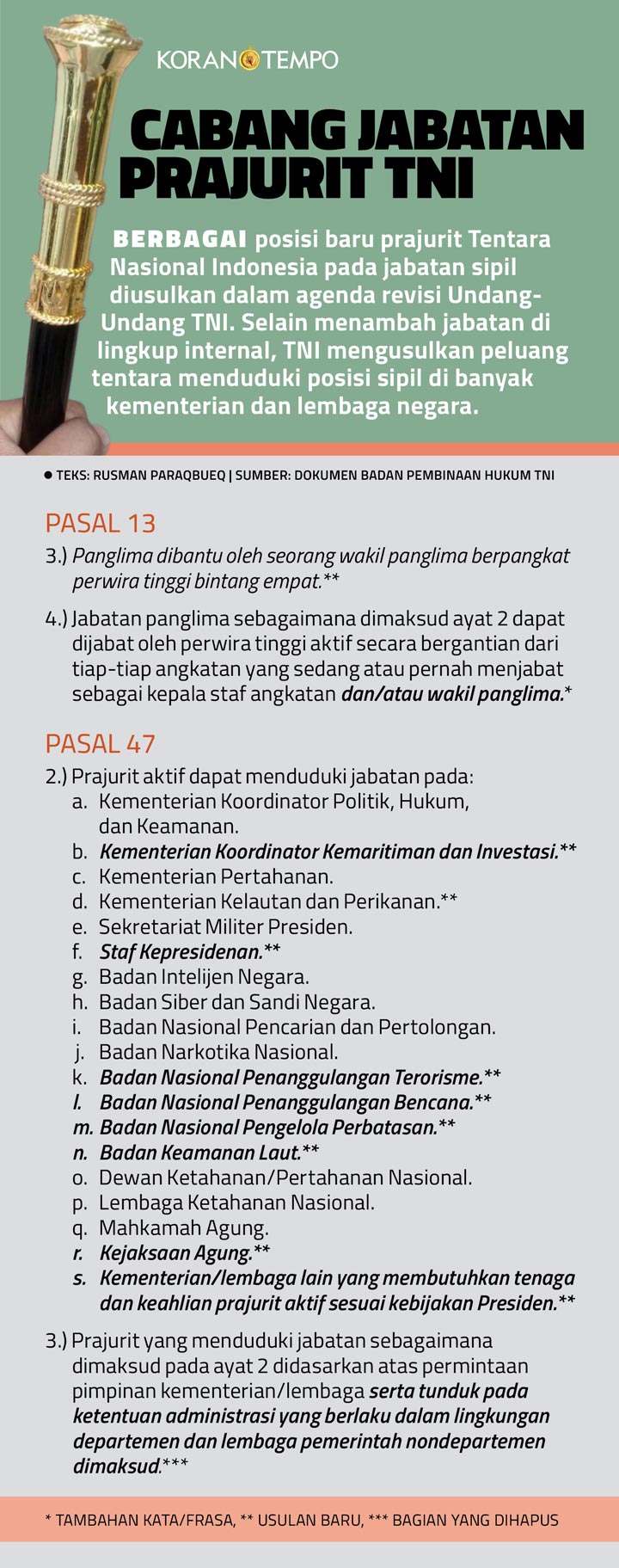

The Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI) is currently drafting a revision of Law Number 34/2004 Concerning the Indonesian National Armed Forces. According to a draft of the document from the TNI Legal Development Agency of April 2023, it is proposed to expand the range of civilian positions in ministries and state institutions that can be filled by TNI officers from 10 to 19 ministries and agencies.

The expansion of positions available to soldiers is reflected in the proposed revision of Article 47 paragraph 2 of the law. For example, soldiers could hold positions in the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) and the Attorney General’s Office. Moreover, it is proposed that the TNI would be able to hold positions in any ministry or state institution, as long as this aligned with the president’s policy.

Mr. Husein Ahmad, a researcher at the civil society organization Imparsial (Impartial), argued that placing the military outside of its function as an instrument for national defense would weaken the professionalism of the TNI. In a democratic state, he said, the primary function and duty of the military is national defense. The army, he added, is not designed to hold civilian positions. “Professionalism is built by placing the military in its original function as an instrument of national defense, not placing it in other civilian functions and positions that are not within its area of competency,” said Mr. Husein.

Mr. Ikhsan Yosarie, a researcher at the SETARA Institute for Human Rights and the Security Sector, agrees with Mr. Husein. Mr. Ikhsan believes there is currently no urgency to place active-duty soldiers in government ministries and state institutions. Typically, he said, the TNI fills civilian positions during emergencies.

According to him, the proposed points for revising the TNI Law are efforts to revive the dual function of the New Order era ABRI, which breaches People’s Consultative Assembly Resolution No. VI/2000 mandating a separation between the armed forces and the police. However, the TNI should only play a role as an instrument of national defense. “Occupying civilian positions deviates from the proper role and function of the TNI and is a cause of the stagnation in the country’s democratic foundations,” said Mr. Ikhsan.

He argued that active-duty soldiers occupying civilian positions would have difficulty making democratic decisions. This is because military culture applies a command system to its members. Additionally, ministries or state institutions typically prioritize accountability and transparency, which are not compatible with military culture. “Placing active-duty soldiers in civilian positions should happen consistently with the requirements of national defense,” he said.

Military observer Mr. Khairul Fahmi questioned the new proposals in Article 7 paragraph 2 letter b number 19 and Article 47 paragraph 2 letter s. Article 7 paragraph 2 letter b number 19 allows the TNI to carry out additional tasks determined by the president to support national development. Then Article 47 paragraph 2 letter s allows the military to serve in ministries or other institutions according to the president’s policy.

Mr. Khairul considers these two points highly dangerous because it is not known whether the ministries and other institutions referred to relate to the TNI’s area of competence or not. If the ministries and other institutions referred to are not related to the TNI’s areas of competence, it has the potential to bring the military back into politics. “That goes against the mandate of the 1998 national democratic reforms,” said Mr. Khairul.

As for the Executive Director of Imparsial, Mr. Ghufron Mabruri, he believes that expanding the space for soldiers to hold civilian positions is a measure in the direction of legally entrenching erroneous policies. Because, until now, many active-duty TNI soldiers have held civilian positions such as in the National Disaster Management Agency, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, and State-Owned Enterprises. “Clearly, these placements violate the law,” said Mr. Ghufron.

Old Plan

Over the past four years, the discourse on the placement of active-duty TNI soldiers in civilian positions has sparked controversy. In the 2019 annual TNI Leadership Meeting, then commander of the TNI, Air Chief Marshal Hadi Tjanjanto (2017 to 2021), proposed changes to the structure of the TNI and revisions to the TNI Law. He wanted positions in ministries and institutions at first- and second-tier senior executive level to be occupied by active-duty TNI with a minimum rank of colonel.

This plan was motivated by the over-abundance of high and mid-ranking officers who lacked promotions positions within the TNI. Air Chief Marshal Hadi hoped that expanding civilian positions which were available to be filled by active-duty TNI members would reduce the number of officers without positions, from 500 to 150-200.

At the time the idea sparked criticism from academics and pro-democracy and human rights activists. They believed the plan betrayed the 1998 democratic reform agenda that prioritizes civilian supremacy. They feared that placing active-duty soldiers in civilian positions would serve as a gateway to the return of the military’s New Order era dual function.

After fading into obscurity, the controversy surrounding the plan to place active-duty TNI soldiers in civilian positions resurfaced in public discussion in August last year. This time, it was Minister of Maritime Affairs and Investment Gen. (Hon.) (Retd) Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan (2016 to present) who addressed the issue. The former Commander, Army Doctrine, Education, and Training Command (1997 to 1999) stated that the plan to amend provisions in the TNI Law had been under discussion since he was Minister of Political, Legal, and Security Affairs (2015 to 2016).

According to Luhut, if active-duty TNI officers could be placed in ministries and government institutions, there would no longer be high-ranking TNI officers filling unnecessary positions, thus making the organization more efficient. Senior TNI officers would also not need to vie for positions because they could pursue careers outside the military itself. “Actually, the TNI can play a more direct role, and TNI officers don’t all have to become Army Chiefs of Staff, but they can work in government ministries,” Luhut said during the National Gathering of Retired Army Officers on August 5, 2022.

Stirring controversy once again, this discussion was eventually addressed by President Joko Widodo. “I see that the need for it is not urgent yet,” Jokowi said when answering questions from journalists during his visit to Sukoharjo district in Central Java, on August 11, 2022.

In an academic manuscript completed in 2019, the Ministry of Legal Affairs and Human Right’s National Legal Development Agency (BPHN) also outlined the numerous ministries and institutions requesting the placement of TNI officers. For example, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM), in July 2019, requested a change in the Liaison Officer Staff for Maritime Affairs (Susmar) in the Directorate General of Oil and Gas for the 2019-2021 period. There were also requests from the Maritime Security Agency (Bakamla), PT PAL (Persero), the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (KKP), the Coordinating Ministry for Human Development and Culture (PMK), and the Pancasila State Ideology Development Board (BPIP).

Also read: Op-Ed: The Armed Forces, Capital, and Politics By Danang Widoyoko

The number of TNI soldiers placed in 10 ministries and government institutions, has reached 1,481 personnel, with the highest number in the Ministry of Defense. Even before the TNI Law revision proposal, 121 active-duty personnel were placed in institutions outside the 10 ministries regulated by the TNI Law, namely the Maritime Security Agency (Bakamla), the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT), and the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB), the Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs and Investment, the Ministry of Transportation, the Coordinating Ministry for Human Development and Cultural Affairs, the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, the Ministry of Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, and the Pancasila State Ideology Development Board.

The issue has also come under the scrutiny from the Indonesian Ombudsman office. The agency responsible for supervision of government administration found many active-duty soldiers holding dual positions, serving in both the TNI and ministries or institutions while also serving as commissioners of publicly owned enterprises (SOE). The Ombudsman found 27 TNI officers working as commissioners of SOEs in 2020. The Ombudsman deemed the placement of active-duty officers as commissioners of SOEs to be a violation of Article 47 paragraph 1 of the TNI Law.

Last year the Indonesian Ombudsman again became aware of allegations of maladministration in the appointment of Major General (Retd.) Achmad Marzuki as the acting Governor of Aceh in 2022, which also drew scrutiny from the Ombudsman. Four days before Jokowi appointed him, Maj. Gen. Achmad had resigned from active duty in the military.

HQ TNI Dismisses Concerns

Head of the TNI Information Center, Rear Admiral Julius Widjojono, confirmed that the proposed changes to Article 47 paragraph 2 of the TNI Law were to accommodate various practices that had been ongoing in several ministries and institutions. “Because, when the TNI Law was enacted, these bodies did not yet exist,” said Julius.

Julius also argued that currently many active-duty officers have an understanding of national interests and possess the expertise needed by ministries or government institutions. He also argued that the spectrum of (national security) threats is no longer just military, but also non-military, such as assisting in the handling of the Covid-19 pandemic. “This is not considered to be a dual function as during the New Order era, but rather an advanced civil-military relationship,” he said.

Julius explained that the draft revision of the TNI Law is still an internal concept drafted by the TNI Legal Development Agency. The draft has been presented to TNI Commander Admiral Yudo Margono at TNI Headquarters at the end of April. “It hasn’t been accepted by the Commander yet, (but) it’s just a presentation,” said Julius. “So it hasn’t been sent to the Ministry of Defense yet.”

On the other hand, the Academic Draft of the TNI Bill prepared by the National Legal Development Agency (BPHN) of the Ministry of Legal Affairs and Human Rights outlines several reasons for the need to change the TNI Law, which so far has limited the placement of active-duty military personnel in civilian positions to only 10 ministries and government institutions. This limitation is considered inconsistent with several changes in regulations regarding nomenclature and institutions, such as the law regulating government ministries, and the presidential regulation regulating non-ministerial-level government agencies.

This article is based on https://koran.tempo.co/read/berita-utama/481975/agenda-dwifungsi-di-balik-revisi-uu-tni.

In related news:

- https://koran.tempo.co/read/nasional/487712/bahaya-tni-dan-polri-masuk-sipil

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/03/23/14380571/panglima-tni-ganti-posisi-kepala-bais-dari-letjen-rudianto-ke-mayjen-yudi

- https://majalah.tempo.co/read/nasional/171114/dwifungsi-tni-jokowi

- https://www.kompas.id/baca/polhuk/2022/01/21/naper-al-araf-dari-pertanahan-ke-pertahanan

Leave a Reply