Will Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission Be Paralyzed During the Term of President Jokowi?

By Budiman Tanuredjo, Kompas Daily, July 4, 2017

KOMPAS, Jakarta – The right of inquiry (hak angket) is a constitutional right of Indonesia’s House of Representatives. No one can deny this. Article 20A Paragraph 2 of the 1945 Constitution explicitly regulates this right of inquiry. During Indonesia’s period of parliamentary government in the 1950s, the right of inquiry was also regulated by statute by Public Law No. 6/1954 Concerning the Right of Inquiry.

The History of House Inquiry Committees

In Indonesia’s history, the House of Representatives’ right of inquiry was first used in 1959 in a resolution by R.M. Margono Djojohadikusumo1 that the House use the right to inquire into attempts by the government to obtain foreign exchange reserves, and how the reserves were being used. As recorded by Subardjo in The Use of the Right of Inquiry by the Indonesian House of Representatives in Overseeing Government Policy, a committee of inquiry during the first cabinet of Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo (30 July 1953 to 12 August 1955) was given six months. However, this was subsequently extended twice, and the committee completed its work in March 1956, during the administration of Prime Minister Burhanuddin Harahap (12 August 1955 to 24 March 1956). Unfortunately, the fate of this committee of inquiry and its results are unclear.

During the New Order period, the House of Representatives also used the right of inquiry several times in relation to the case of the state-owned oil company Pertamina. However, efforts to shake the New Order government failed and were rejected by a plenary session of the House. The New Order government was strong enough to prevent the use of the right of inquiry, initiated by Mr. Santoso Danuseputro (PDI) and HM Syarakwie Basri (FPP).

In the Reformasi (Reform) period, the right of inquiry has also been used. However, all the targets of the right of inquiry have been the government, and this is consistent with the legislation.

Legislation on the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), House of Representatives (DPR), Regional Representatives Council (DPD) and regional legislative assemblies (DPRD) regulates the right of inquiry. Article 79 concerning the Rights of the House of Representatives provides, among other things, that the House of Representatives possesses the right of inquiry. The right of inquiry is the right of the House of Representatives to investigate the implementation of a law and/or government policy which is related to important, strategic matters, and which has a wide-spread impact on the life of the community, nation, and state which allegedly conflicts with the law. The legislation also provides that an inquiry committee must be joined by every House of Representatives’ faction.

From the standpoint of legality, the House of Representatives Committee of Inquiry into the KPK does not satisfy the requirements for legality. Historically, the right of inquiry was given to the House of Representatives to investigate government policies that conflict with the law. Whether it was the New Order government, or post-Reform governments, it has only been the current 2014-2019 House of Representatives which has innovated by using the right of inquiry for a national commission, here the KPK. The KPK is not the government. The KPK is a law enforcement agency.

The law also requires that an inquiry committee draw members from every party faction in the House of Representatives. Therefore, when the Democratic Party (DP), Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), and National Awakening Party (PKB) House factions each failed to send representatives, the jurisdictional legitimacy of the Committee of Inquiry became problematic.

Members of the public in the Healthy Indonesia Movement unfurled posters and banners in front of the offices of the KPK in Jakarta on Thursday June 15. Consisting of writers, artists, and anti-corruption activists, the crowd declared that it rejected the inquiry currently being rolled out by the House of Representatives.

From a political perspective, those who initiated the use of the right of inquiry are overwhelmingly from the parties which support the government. They are the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) House faction, the main supporter of the government of President Joko Widodo, together with the National Democratic Party (Nasdem), and the People’s Conscience Party (Partai Hanura). This coalition of government supporters is the group that has been keen to urge the use of the House right of inquiry.

House Inquiry Committee into the Corruption Eradication Commission

The actions of the current House of Representatives Inquiry Committee into the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) have become more and more absurd. The Committee of Inquiry is going on safari to Pondok Bambu and Sukamiskin prisons to meet with inmates convicted of corruption offenses. The Committee hopes to uncover evidence of how these corruption felons were mistreated by the anti-corruption commission.

“We want to look for information about anything inappropriate experienced by the prisoners while they were either witnesses, suspects or prisoners convicted in corruption cases,” said Deputy Chairman of the Inquiry Committee Rep. Risa Mariska (PDI-P-West Java), the representative for the district including Bogor and Bekasi. She said the Inquiry Committee has received information about the improper treatment of the prisoners while they were being interrogated by the KPK.

There is little doubt the Inquiry Committee will have any trouble meeting any of the many corruption prisoners. Take the former Chief Justice of Indonesia’s Constitutional Court Akil Mochtar, for example, or former Democratic Party Representative and party treasurer Mr. Muhammad Nazaruddin, former Democratic Party Representative and party secretary-general Mr. Anas Urbaningrum, former Democratic Party Representative Ms. Angelina Sondakh, former Banten province Governor Atut Chosiyah, or any number of others. It isn’t hard to guess that they will provide any amount of ammunition with which to damage the KPK as an ad hoc institution, ending eventually in the KPK being either abolished or neutralized.

Parahyangan University criminal law lecturer Agustinus Pohan believes the effort of the Inquiry Committee is an attempt by politicians to take revenge on the KPK. “Now the fight against corruption has to contend with white-collar criminals who want to prove their ability to exact payback,” Pohan said.

Earlier, Deputy Chairman of the House Inquiry Committee into the KPK, Rep. Taufiqulhadi (Nasdem-East Java) planned to call constitutional law experts to prove the legality of the Inquiry. “Some say this inquiry isn’t appropriate. Different opinions are all right, but we hope the debate stays balanced,” said the National Democratic Party2 politician, according to Kompas on 30 June 2017.

The Inquiry Committee action in calling constitutional law experts Prof. Dr. Yusril Ihza Mahendra and Prof. Jimly Asshiddiqie to appear will be a priority before it summons Rep. Miryam S. Haryani (Hanura-West Java) who has been arrested by the KPK. Ms. Miryam was named a suspect by the KPK over allegations she provided false information. Her case goes to trial soon.

The origins of the House Inquiry Committee started when the KPK leadership rejected requests from House of Representatives Commission III to make public recordings of the questioning of Rep. Miryam Haryani by KPK investigators. The KPK refused to make the recordings public before her trial. Up till now, recordings of wiretaps have always been made public during trials. Having previously appeared as a witness in the Criminal Corruption Court, Rep. Miryam retracted part of her testimony contained in the brief of evidence, giving as the reason that she was coerced by KPK investigators.

In response to Rep. Miryam retracting her testimony in the brief of evidence, senior KPK investigator Mr. Novel Baswedan was examined as a witness in the trial. Mr. Novel testified that there had been no intimidation or coercion, going so far as to claim that Rep. Miryam had been induced by certain fellow members of the House of Representatives to retract her testimony in the brief of evidence, mentioning several names, including Rep. Bambang Soesatyo (Golkar-Central Java) and Rep. Masinton Pasaribu (PDI-P-Jakarta II)3, as the members who had influenced Rep. Miryam Haryani. She denied ever having mentioned their names, and from this House Commission III requested that the KPK make the recordings public, which it refused to do.

Whether it is related or not is unknown, however, several days after testifying, Mr. Novel Baswedan was the target of an acid attack by an unknown assailant. His eyesight was damaged. He was taken to hospital, and is still receiving ongoing treatment. Police are still investigating the case, but so far the person who sprayed Mr. Novel with acid has not been identified.

After undergoing further questioning at the KPK’s Jakarta offices on Wednesday 21 June, Hanura Party politician Rep. Miryam S. Haryani’s brief of evidence was declared complete (that is, Form 21 was issued) and ready for trial in relation to the allegation she had provided false testimony during the electronic identity card (e-KTP) project implementation corruption trial.

Strong Resistance

The House of Representatives Inquiry Committee into the KPK apparently needs to find political support from constitutional law experts. Earlier, 357 academics from various universities and disciplines published an open letter rejecting the House Inquiry Committee into the KPK on a number of grounds. The 357 academics included Prof. Dr. Mahfud MD, Prof. Dr. Denny Indrayana, Prof. Dr. Rhenald Kasali, and many other prominent academics.

Calling experts in constitutional law, or calling anyone else, is clearly completely valid. The Inquiry Committee obviously has statutory authority to do this. No one denies that the House of Representatives has a right of inquiry, the right of interpellation, and the right to express opinions. However, what has, in fact, become an issue is whether it is proper for the House to exercise the right of inquiry in relation to the KPK. The KPK is a law enforcement agency and an independent authority, not part of the government. Is the use by the House of Representatives of the right of inquiry consistent with the will of the people it represents?

Resistance to the use of the House of Representatives’ right of inquiry for the KPK has indeed been strong. The open letter of the 357 academics from numerous universities and disciplines is one expression of this. These academics have very clearly framed the intention of the House of Representatives in using the right of inquiry as being to weaken the KPK. The academics have rejected the use of the House right of inquiry for the KPK.

At present, the KPK is investigating a case of alleged corruption involving the procurement of a national electronic identity card (e-KTP) involving a number of House members, including House Speaker Rep. Setya Novanto (Golkar-East Nusa Tenggara), now banned from traveling overseas. The alleged loss to the public revenue is not insubstantial.4

A Kompas poll of Monday May 8, 2017 also contained the same message. As many as 58.9 percent of respondents said the House decision to use the right of inquiry did not represent the interests of the community, while 35.6 percent thought it did represent the interests of the community. Most respondents (72.4 percent) believed the use of the House right of inquiry into the KPK was related to the KPK’s investigation into the e-KTP project corruption case.

In the virtual world, internet user Virgo Sulianti Gohardi gathered support for a petition against the right of inquiry on the site Change.org. As of midday, Friday May 30, 2017, the petition had been signed by 44,350 people. Virgo’s target for the petition was 50,000 signatures.

In terms of representation theory, the formation of the House of Representative Committee of Inquiry into the KPK really does not have social legitimacy, or it has a very low level of representation. What’s more, the Democratic Party (PD), Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) and National Awakening Party (PKB) House factions have each refused to join the Committee of Inquiry.

“The Democrats are not responsible for anything in the Inquiry Committee,” said House Deputy Speaker from the Democratic Party Rep. Agus Hermanto (DP-Central Java) at the House of Representatives building, while stressing that the Democratic Party does not agree with the House Committee of Inquiry into the KPK.

“We reject the weakening of the KPK through the inquiry. The Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) is being consistent by not sending any members, but the PKS is still critical of the KPK,” said the head of the PKS Advisory Council, Rep. Hidayat Nur Wahid (PKS-Jakarta)5. National Awakening Party (PKB) Chairman Rep. Muhaimin Iskandar (PKB-East Java) was also of the same opinion, rejecting the use of a House committee of inquiry into the KPK.

Then There is President Joko Widodo

Then there is President Joko Widodo. He has been taken hostage by party officials of his own PDI-P. President Jokowi has said he cannot interfere in the affairs of the House of Representatives, because a committee of inquiry is the business of the House. President Widodo hoped only that the KPK is further strengthened.

President Joko Widodo’s attitude towards the KPK feels different this time. When there was a conflict between the KPK and the Indonesian National Police, with the public supporting the KPK, President Widodo took a firm political position in support of the KPK. Likewise, when the KPK investigator Mr. Novel Baswedan was to be arrested, President Widodo called loudly for Mr. Novel not to be arrested. However, this time, President Widodo is like a hostage, allowing the KPK to be de-legitimized by a coalition of his own supporters in the House of Representatives.

Will the KPK be paralyzed during the term of President Joko Widodo? History will record the answer.

This article is based on: Akankah KPK Lumpuh di Era Presiden Jokowi? (Also see Melunasi Janji Kemerdekaan)

Footnotes:

- Ironically, RM Margono Djojohadikusumo was the grandfather of Prabowo Subianto. See https://tirto.id/jatuh-bangun-dinasti-djojohadikusumo-dalam-politik-indonesia-cLjy or https://doi.org/10.1177/0967828X16659728. ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nasdem_Party ↩︎

- Rep. Masinton Pasaribu (PDI-P-Jakarta II) – See https://www.dpr.go.id/blog/profil/id/1390; https://twitter.com/Masinton; https://t.co/jRsIuncUHm ↩︎

- For a detailed summary and some references to this issue see https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasus_korupsi_e-KTP#Setya_Novanto. ↩︎

- For a detailed summary and some references to this issue see https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasus_korupsi_e-KTP#Setya_Novanto. ↩︎

In related news:

- https://majalah.tempo.co/read/nasional/171233/manuver-ppp-suara-pemilu

- https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1851017/respons-puan-maharani-pkb-hingga-gerindra-soal-progres-hak-angket-pemilu-di-dpr

- https://x.com/KompasTV/status/1766056812846190779?s=20

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/03/04/11193931/survei-litbang-kompas-622-persen-responden-setuju-hak-angket-untuk-selidiki

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/03/03/19482341/jimly-asshiddiqie-hak-angket-ini-untuk-memindahkan-kemarahan-publik-ke-ruang

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/03/02/19185331/era-jokowi-tak-ada-hak-angket-jimly-10-tahun-kok-dpr-nya-memble

- https://x.com/tempodotco/status/1763481714834411588?s=20

- https://regional.kompas.com/read/2024/03/01/171350678/spanduk-tolak-kedatangan-jokowi-terpasang-di-pagar-gedung-dprd-sumsel

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/02/27/09575351/megawati-dukung-hak-angket-ubah-hasil-pemilu-mahfud-anggap-bisa-berujung

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/02/27/21101401/ramai-wacana-hak-angket-menko-polhukam-diharap-bijak-tanggapi-isu-politik

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/02/22/19552191/3-partai-koalisi-perubahan-siap-dukung-hak-angket-selidiki-dugaan-kecurangan

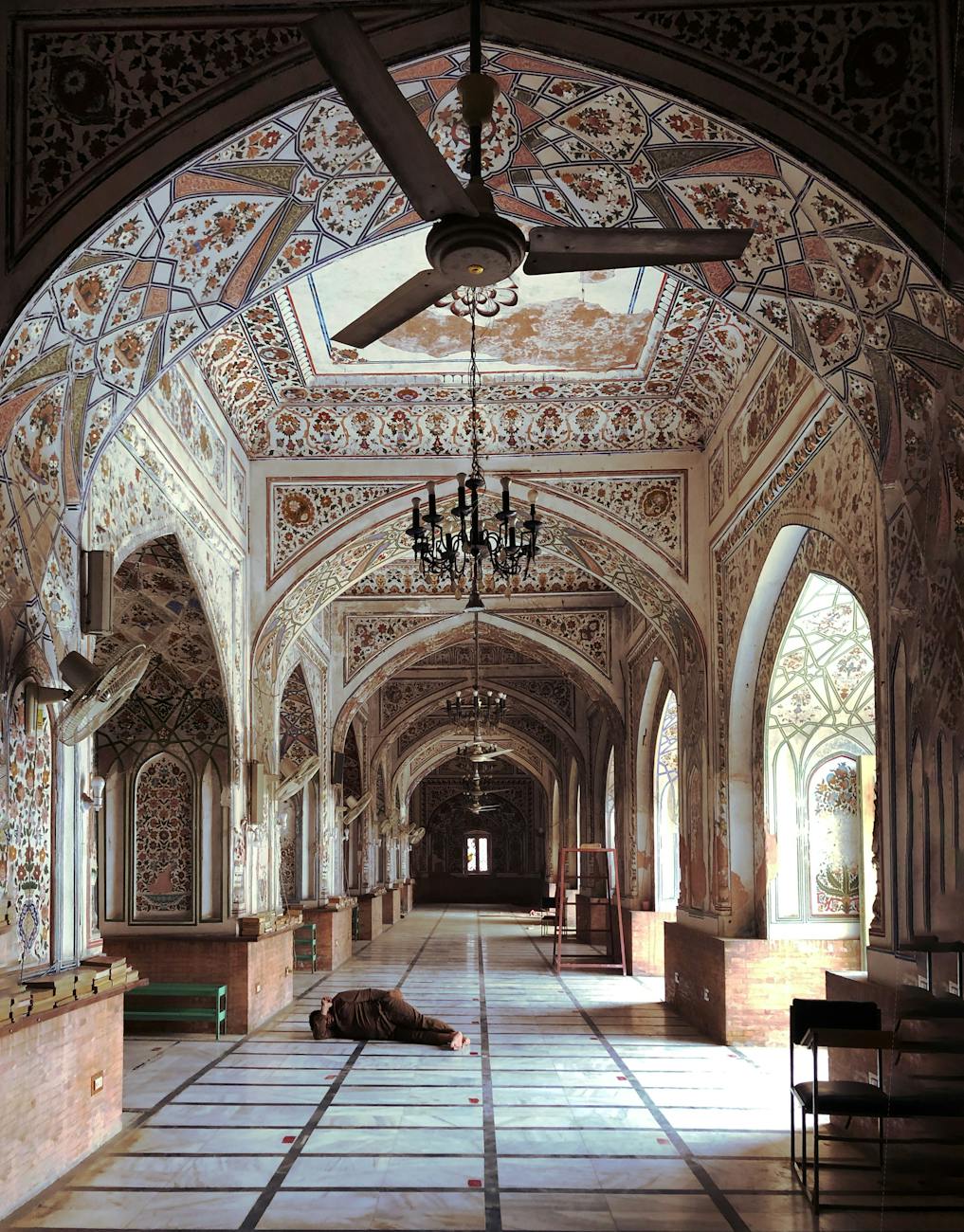

Featured image credit: Temple of hope: Door to Nirvana, Created by Entang Wiharso, 2018-2019, NGA, https://searchthecollection.nga.gov.au/object/319692

Leave a Reply