Half-Hearted Energy Transition, Built Only to Die

By Sartika Nur Shalati for Project Multatuli, March 21, 2024

MR. SULKIFLI, 45, let out a heavy sigh as he glanced at the election campaign flags of various political party that lined the village’s main road in late December 2023. In his village of Way Haru, in Lampung province on Indonesia’s Sumatra Island, residents have yet to enjoy the benefits of electricity, despite the village being founded over two hundred years. The village is only 165 miles from the nation’s capital Jakarta.

In this village, home to at least 2,700 residents of the traditional Belimbing clan, the community have committed for decades to not harming the forest in order to make a contribution to the protection of the Southern Bukit Barisan National Park (TNBBS) protected area in Lampung province.

“I no longer believe in elections, whoever becomes president, it doesn’t matter,” said Sulkifli, greeting a relative passing by his house, leading an ox cart loaded with mud.

In the past, at every election season, Sulkifli would travel around the village collecting voter data. For the three consecutive presidential elections starting in 2009, he served as a local village election committee member. He also never missed voting for one of the presidential candidate with the most community-centered campaign ideas.

Now, he rejects all invitations and the sweet promises of politicians, citing disillusionment and minimal realization. “Elections only bring empty hopes for the people. If you think about it, is there really hope for us?”

Sulkifli is one of four residents who once operated a centralized solar power plant in Way Haru Village in Bengkunat sub-district in West Pesisir Regency.

Local residents were accustomed to walking dozens of kilometers for 6 hours to transport food and fuel supplies from the nearest market. This market is located in Way Heni, Pekon Penyandingan, a mere 9 miles, which is still in the same district as Way Haru village. Access to the village is only available by motorcycle. During the dry season, the travel time is about 2 hours, but during the rainy season, it can take 2-3 times longer due to flooded and muddy roads.

Way Haru village is located within the Southern Bukit Barisan National Park (TNBBS) and is bordered by the Indian Ocean. The village’s location in the middle of a conservation area makes it difficult for the national state-owned monopoly electricity producer and distributor, PT PLN (Persero), to supply electricity, mainly hindered by land acquisition problems, permit processing issues, and environmental impact assessment requirements.

Despite numerous changes in leadership, from presidents to village heads, none have succeeded in bringing the national electricity grid into the village. Development efforts have failed due to the government’s signature top-down practices: building without communicating with the local community who are the intended beneficiaries.

Centralized Solar Power Station Fails, Owned by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM)

At the end of 2016, the centralized solar electricity generator (PLTS) built in Way Haru Village was the first opportunity for the community to enjoy electricity. There were 682 families from 280 houses who benefited from it.

At the time, the village head, Mr. Dian Setiawan, felt the excitement of the residents. They were willing to walk up to 8 hours covering a distance of 9 miles, crossing muddy roads and skirting coastline.

They carried poles, using oxen and carts to transport equipment. This illustrated how enthusiastically the residents of Way Haru welcomed the solar electricity plant that would bring life to the village. The village government donated land for the solar plant’s construction. Dian even took the initiative to dip into his own pocket to pay villagers Rp50,000 ($3.30) per day.

After its completion, Sulkifli, a junior high school graduate with additional post-school certificates, was appointed as the operator of the centralized solar electricity generator. Along with Sultoni, he went to Jakarta for three weeks of basic technical training on the operation of small solar power generators. Two others were trained in the village by operators from Jakarta during the solar power plant’s trial period, the only chance for residents to experience uninterrupted electricity for 20 days.

After the solar power station was operational, residents only paid a monthly fee of Rp10,000 ($0.60) as operational fees.

The trial period ended. The training operators left the village. Then, electricity access for residents was reduced to 12 hours, from evening to morning, with each house allocated 200 watts. Sulkifli and his three colleagues performed their duties with the knowledge gained from the training without any support. “There were no problems for several months because it was just checking cables, chargers, pressing the on-off button, and monitoring,” he said.

Months later, the operators were overwhelmed because the solar power station with a capacity of 75 kilowatt peak (kWp)—75,000 Wp—was often plagued by technical issues. Fortunately, the central operators regularly came when they received reports of damage.

Over time, the duration of the electricity flow decreased further. Only 5 hours, from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m., as the generating capacity weakened.

Various solutions were sought until nearly a year later, the solar power station’s condition deteriorated, and the central operators no longer responded, let alone came out to the village. Three operators besides Sulkifli resigned because the solar power station completely shut down. “We approached everyone, but there was no answer,” Sulkifli recalled.

Rooftop Solar Generation More Appropriate

The construction of the solar power station in Way Haru Village took two months, coinciding with Mr. Dian Setiawan’s election as village head.

Based on documents seen by Dian, the project owned by PT Industri Telekomunikasi Indonesia (Persero) (a state-owned enterprise specializing in telecommunications equipment) was worth more than Rp10 billion ($670,000). Ideally, these funds should have cover the entire project, including transportation costs, which instead used Dian’s personal funds of Rp17.4 million ($1,160).

No one expected the solar power station to end up as a skeleton. Its location on the edge of the village road across from State Elementary School No. 025 Krui. Overgrown with bushes, the stranded solar power station looked pathetic. Every month for a year after it was closed, residents and village officials cleared grass and dry leaves at the site, hoping that someday the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources would come and the solar power plant would operate again.

But, nothing happened!

The residents were puzzled. There was no mechanism for reporting damaged solar power plants. It was unclear where and to whom to complain. All the village residents could do was wait. In early 2023, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources invited village head Mr. Dian to a meeting. Explaining that after construction, the solar power plant was indeed to be handed over to the regional government or village.

The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources had previously asked West Pesisir Regency Head Mr. Agus Istiqlal for approval to transfer the responsibility of the solar power plant from the central to the local government. This effort failed because the regency head refused to sign the grant letter accepting the transfer. “The reason was that the solar power plant had to be repaired first before being given to the village government. Don’t transfer it in a damaged condition,” said Dian, quoting the regency head’s statement.

For Dian, the handover of the solar power plant in good condition must be accompanied by manuals so that residents are not confused about managing it.

Dian’s statement is in line with the thinking of West Pesisir Regency Deputy Regent Mr. A. Zulqoini Syarif. Mr. Zulqoini is a descendant of the 17th King of the traditional Belimbing clan, who is known as the Sai Batin (highest traditional leader of the clan).

Zulqoini’s reason was that providing electricity is not the responsibility of the regional government, but rather of the central government, in this case, the state-owned monopoly PT PLN.

The regency government lacked the resources to manage the centralized solar power plant and there is no budget allocation for maintenance and repairs. “If the central government pushes the matter, then it can be guaranteed that the result will be like it is now, a failure!” Mr. Zulqoini emphasized.

Coordination from the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources as the project owner to the regions and villages has been unclear since the centralized solar power plant was constructed. The Ministry only advised of the plans to construct the solar power station without making adjustments for the community’s needs.

According to village head Dian, the project’s funds would not be exhausted to purchase solar panels and batteries for each house, with capacities larger than those of the current residents. Dian considers rooftop solar generation to be more sensible than centralized solar plants. “There’s a lot of surplus funds, and residents would be able to use that power to power TVs, washing machines, and other appliances.”

Mr. Sulkifli agrees. As a former operator of the centralized solar plant and a user of rooftop solar power, he says that rooftop solar power would be more effective to build in his village because the access road to Way Haru village is inadequate.

It takes extra time and effort for people to move in and out of the village. If there are any problems, it’s difficult to respond quickly. Moreover, the telecommunications network is poor. If one solar power plant fails, the entire community is affected.

For rooftop solar power generation, the residents of Way Haru have knowledge, from installation to repair, because they have been familiar with the generator since 2000. If it breaks down, which rarely happens, the impact is small, and the repair process doesn’t require waiting for days or months.

Years passed, and without further communication after the last visit, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources issued the approval on April 3, 2023 for the assets to be dismantled, in this case, the centralized solar power station.

On the same date the dismantling work was carried out. The reason for the destruction of the solar power plant, as stated, was because its condition was severely damaged it was not suitable for renovation and relocation, and that it was not economically viable.

Among the many damaged solar power plants’ equipment that were destroyed, there were many solar panels that could still function, which were then distributed to each house with a capacity of 100 watts each. Now residents feel the benefits of the centralized solar power plant through the salvaged solar panels being operated in their own homes to power four lights.

Sunlight or Petrol More Economical?

In the 2000s, the residents of Way Haru village received assistance with solar panels, batteries, cables, and four lights, distributed in limited quantities. The priority was for village officials’ houses and public facilities. The good news was that all residents were taught how to assemble and install solar panels on their roofs. This knowledge was more valuable than just facilities brought in from by the central government.

As soon as they understood how it worked, residents rushed to buy solar panels. Sulkifli and his wife, Eli, traveled all the way to Bandar Lampung to purchase the equipment before they were available in the closer market. Although the price of Rp1.5 million ($100) for a 100-watt solar panel was considered high at the time, they still bought it. The price of a 70-ampere battery was around Rp1.5 million ($100).

With solar panels, Eli only needed to refill the battery with water to keep the power storage system running. “It’s quite economical per month. If you want, you can also connect an inverter to convert the current. But, the power runs out faster too. It has the same function as a power bank, depending on usage,” Eli explained.

After comparing, the price of diesel engines and generators was much more expensive than installing rooftop solar power generation. The price of diesel engines ranged from Rp 2.5 million ($165) to Rp5 million ($365), while the price of generators ranges from Rp2 million ($135) to Rp3 million ($270). Plus, the fuel costs Rp 12,000 ($0.90) to Rp 15,000 ($1.00) per liter.

Some residents who relied on either diesel fuel or generators were spending around Rp 60,000-Rp 75,000 ($5.00) per day for lighting, cell phone charging, laptops, and TVs.

Ms. Marzaya, the owner of the only refrigerator in Way Haru village, combined the power from a 100-watt rooftop solar power generation and diesel fuel to run a canteen business. Although she couldn’t maximize the power for the freezer to produce ice cubes due to low power, she could at least cool drinks.

The power from generators and diesel engines is actually larger than the 100-watt rooftop solar power system in each house. But if the power from the rooftop solar power and battery capacity are increased, this electricity option could be superior.

Spending more money upfront to match its capacity with the monthly (effectively) free electricity bill would be worthwhile. The government should adjust the type of energy and power generation to the community’s needs, including making rooftop solar power an option.

The calculations show that the current off-grid solar panel purchase package of 1,000 Wp is around Rp 21 million ($1,400), without monthly costs, which can be used for 10 to 20 years. This capacity can operate large electronics such as refrigerators, washing machines, and TVs.

Meanwhile, diesel engines or generators with the same capacity typically require Rp1.8 million ($120) per month worth of fuel if used fully. The annual fuel costs for a generator are equivalent to the cost of installing a rooftop solar power system with a useful life of 10 to 20 years.

Claims of Growth in Clean Energy

Way Haru village is just one example. The area that used to span three villages, has now expanded into the villages of Way Tias, Bandar Dalam, and Siring Gading. These three villages experienced the same fate as Way Haru: the solar power plant built in each village no longer works.

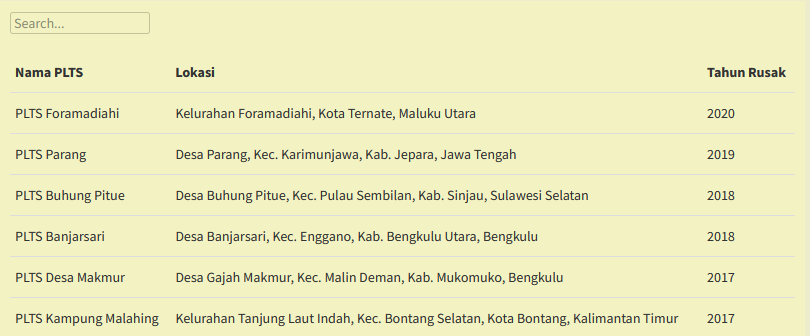

The claim of renewable energy growth reaching 13% in 2023 is questioned: does this figure include failed projects like the one in Way Haru and other locations?

Moreover, the government’s targets are very confusing. In January 2024, the National Energy Policy (KEN) document stated that the renewable energy mix (ET) target decreased from 23% to 17%-19% by 2025 and 19%-21% by 2030. Meanwhile, in the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) investment plan, the ET target is set to reach 44% by 2030. In another document, the “Energy Compact,” the ET is targeted to reach 23% by 2029.

On the other hand, the administration of President Joko Widodo targeted 100% electrification by 2022, referring to the 2021-2030 Electricity Supply Business Plan (RUPTL). However, this target has not been achieved.

The number of villages still needing electrification is about 3,095 across Indonesia through the village electricity program, which unfortunately does not include rooftop solar power systems as part of its scheme.

The reasons are (1) the capacity of rooftop solar power systems is limited according to PT PLN’s system capability; (2) the impact of rooftop solar power generators on PT PLN’s Production Costs (BPP) would place a burden on the company’s subsidy/compensation costs; and (3) there are no transactions in the rooftop solar power generation business scheme.

The case of stranded solar power generation is like a ticking time bomb, with the number estimated to increase every year if the government’s management and communication patterns do not change.

From a variety of reports, the same pattern emerges: communities are not consulted and not equipped with adequate technical capacity to address the various technical challenges of solar power generation, as well as the confusing responsibility-sharing scheme established since the project’s inception.

In Way Haru village and its surroundings, the limited electricity supply has forced most residents to revert back to petrol and diesel. This means that besides failing to illuminate the four villages in Bengkunat District, the centralized solar power plant project also failed to realize the energy transition from fuel oil to diesel energy in the region.

One of the impacts is the limitation this imposes on the economic mobility of residents. In Way Haru village, Eli aspires to follow in Ms. Marzaya’s footsteps: opening a small shop, and retailing food. However, her electricity supply is inadequate.

“Where will we get electricity if we want to use a blender, mixer, and refrigerator? We can’t use a generator or diesel because we’re afraid of making a loss,” she explains.

Moreover, the limited electricity disrupts educational activities. Ms. Endang Murjianto, principal of State Elementary School No. 025 Krui, feels this impact. Teachers charge their laptops at night, racing against battery power to complete everything they have to do: from preparing teaching materials to inputting data and grades.

For the students, life outside the village becomes inaccessible as long as electricity remains limited.

Sartika Nur Shalati is a researcher at CERAH, a non-profit organization focusing on energy transition policy agendas in Indonesia.

This article is based on https://projectmultatuli.org/transisi-energi-setengah-hati-setelah-dibangun-sudah-itu-mati/.

In related news:

Leave a Reply