The Glass Wall

A Short Story by Mochtar Lubis (1950)

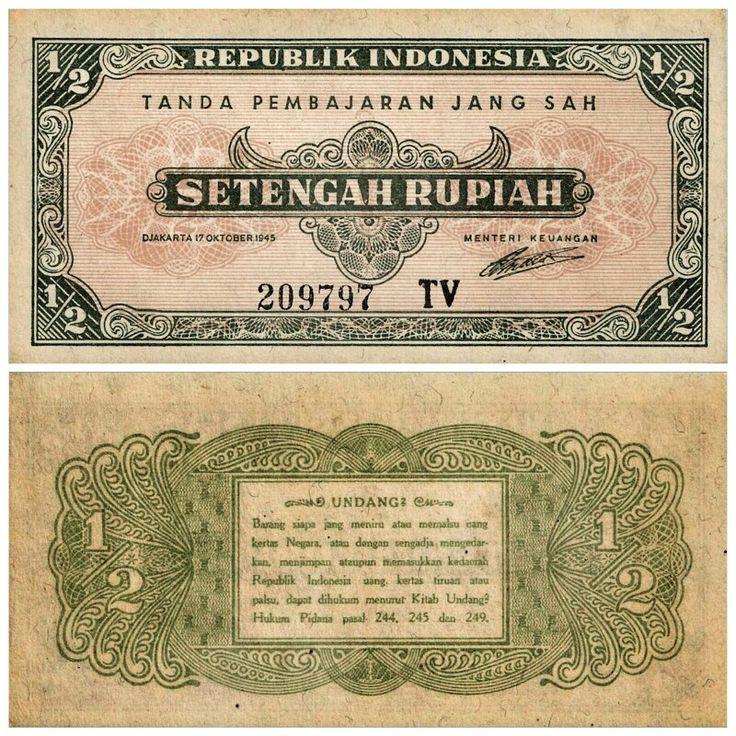

The man calls a trishaw. It is very rare actually for them to go anywhere by trishaw. They walk usually and only take the tram if it’s too far. But today Dulah feels they should go by trishaw. It’s a special day. Today, the two of them, Dulah and his wife, are going shopping for his wife. Dulah is employed as a clerk in an office, and with New Years approaching, he’s received a decent yearly bonus. They sit in the trishaw, huddled close together like newlyweds. Every now and then Dulah’s hand feels the envelope containing the money in his coat pocket. Sixty-five rupiah.

Dulah strokes his wife’s wrist. With his simple heart, Dulah loves his wife deeply. “You can choose whatever you like,” he says.

His wife pinches his thigh and laughs, saying she wants to choose a necklace, a silk blouse, a red comb, colored hair clips, a shawl, a long skirt, and new slippers. Dulah laughs. He says there isn’t enough money to buy everything, but his wife can spend all the money, and they laugh together. When the trishaw comes to a halt in front of the shops, they climb down and Dulah hands the driver a half rupiah note.

“What do you mean, only half a rupiah?” the trishaw driver grumbles.

Dulah adds another quarter.

“That’s not enough. It’s a long way! Only a quarter!” the trishaw driver insists. Normally, he would not pay any more and would rather be abused by a trishaw driver than be overcharged. But today Dulah doesn’t like the thought of their happiness being disturbed by an argument with the driver. He adds another twenty-five cents.

“Let’s look around first,” his wife says.

So, they set off browsing at the goods displayed behind the shop windows, moving from one store to another. Every now and then, as his wife sees something that catches her eye, they stop and stand close to the window. They press their faces against the window until the tips of their noses are pressed against the glass. Each time they do this, strange thoughts flash through Dulah’s mind and then disappear again. Flash past again and then vanish again. Especially when his wife says, “Hey, look at that shirt, dear. That would really suit you. And look at those business shoes!” His eyes look at the ties, shoes, jackets, shirts, trousers, and hats—reminding him of his boss at the office who comes and goes in a big car wearing the same ties, shoes, jackets, shirts, trousers, and hats that he’s looking at behind the store windows. And into his mind drift thoughts of large buildings, airplanes, steamships, another world—a glittering world full of pleasure and luxury of which he has never tasted. A few times he wanders far away with these thoughts until his wife grabs his hand, and says, “Come on, you. Let’s keep going.” Dulah turns and looks around, then gazes at the things behind the glass. The glass. The glass lies forever between him and those goods from that other world. He can see them, but he cannot touch them. They keep walking.

Then Dulah smiles. This time, he thinks, they will go in and he will be able to buy what’s behind the glass for his wife. He remembers the money and quickly puts his hand into his coat pocket. He’s relieved that the envelope of money is still there.

Then his wife pulls him into a shop. It takes a long time for them to be served by the attendant. And the person is not as respectful to them as he is to others. But Dulah and his wife do not feel the difference.

“What would you like to buy?” the attendant asks.

Dulah’s wife points to a fabric.

“Thirty rupiah per meter.”

“How much is one blouse?” Dulah’s wife asks.

“Fifty rupiah,” the salesman says.

Dulah’s wife looks at her husband in surprise. Dulah’s face turns pale when he hears the price.

“Let’s look elsewhere first, dear,” his wife says.

Dulah nods and they leave the store. But the prices are the same everywhere. Entering each store, Dulah loses track of how many they have tried—it’s always fifty rupiah, forty-five rupiah, sixty rupiah.

Finally, Dulah’s wife says, “It’s expensive inside the stores. It would be better if we bought outside, dear.” At last, they find a blouse for twenty rupiah, a shawl for ten rupiah, and a long skirt for twenty-five rupiah.

“There’s only ten rupiah left,” says Dulah.

“Never mind, dear. Let’s go home,” his wife replies. Dulah calls a trishaw. His wife gets in, and as he is about to sit down, he suddenly stands up again, and says to her, “Wait a moment.” He quickly steps back into the store.

A moment later, he comes out smiling, carrying a small package.

He sits in the trishaw beside his wife and hands her the small package. His wife opens it… There are six colored hair clips: red, yellow, white, green.

“Only one rupiah,” says Dulah.

“Oh, that’s great, dear,” his wife replies. “Thank goodness you remembered.”

Dulah laughs and puts his arms around his wife. He does not say why he suddenly went back to buy the hair clips he saw behind the shop window. Because by doing this, Dulah feels he has succeeded in penetrating the glass wall that separates him from the things behind the glass—things that remind him of the other world he has been longing for, even though he didn’t realize it.

“Let’s make it just the hair clips for now…,” Dulah thinks.

Source: Tembok Kaca (The Glass Wall) is a short story from Mochtar Lubis’s short story collection, Si Djamal: dan tjerita2 lain/ by Mochtar Lubis, Gapura, Djakarta, 1950, p. 80. Featured image credit: The shopfront of Au Bon Marché on Rijswijkstraat 20 (now Jalan Majapahit) in 1936, Photo Credit: Blog post, Jalan Majapahit 1936, by Sven Verbeek Wolthuys, January 13, 2023. LostJakarta.com, https://lostjakarta.com/2023/01/13/jalan-majapahit-1936/.

Shops on Rijswijkstraat (Majapahit Street) in Batavia, 1935

Leave a Reply