The Illusion of Trump’s Board of Peace

By A.D. Agung Sulistyo, for Tempo.co January 30, 2026

Indonesia’s decision to join President Donald Trump’s Board of Peace for Gaza is anything but neutral. It bristles with ethical problems.

This choice, made by Indonesia to participate in the Board of Peace for Gaza established by President Trump, is framed in familiar clichés: active involvement, a commitment to global stability, and a dedication to peace.

However, Indonesia’s membership in this U.S.-controlled peace forum actually presents a dilemma: stand firm in upholding the rules-based international order or participate and risk gradually diminishing the significance of the United Nations Charter.

Since World War II, peace has never stood alone as a goal in international law. It has always been accompanied by procedures, mandates, and limitations on power. Pursuing peace without a legal framework is akin to establishing a new, subtler form of domination. Consequently, the responsibility for maintaining peace is entrusted to the Security Council. This is not because the institution is perfect, but because its authority is anchored in collective representation and legitimacy.

When the White House describes the Trump Board of Peace for Gaza as an initiative aligned with UN Security Council Resolution 2803, a more fundamental question arises: Is world peace still governed by law, or is it beginning to be determined by those in power who are merely using legal language as a diplomatic facade?

A policy may appear to align with the UN’s objectives, but that does not automatically confer legal validity. A UN Security Council resolution is not a blank check. If a resolution does not explicitly establish a body—including its structure, mandate, and accountability—then legally that body does not exist.

Herein lies the tenuous nature of the White House’s claim. UN Security Council resolutions—under Chapter VII of the UN Charter—has never created new bodies through vague interpretations or ulterior motives. International organizational law recognizes the principle of express mandate which asserts that authority must be explicitly stated and cannot be assumed. Without this clarity an action is ultra vires—an action beyond the limits of legal authority.

Article 24 of the UN Charter clearly asserts that the primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security rests with the UN Security Council. This is not merely a division of administrative duties; it is a constitutional rule in the post-1945 world order. If this function were carried out by another mechanism outside the authority, oversight, and accountability of the UN Security Council, it would amount to a tacit takeover.

What we are witnessing now is a hollowing out of the UN’s functions. The Charter is still cited, and resolutions are still referenced, but crucial decisions about peace are being transferred to a forum serving the interests of the powerful. This represents a new form of defiance against international law.

Indonesia’s decision to join is clearly not a neutral step. By participating, Indonesia indirectly acknowledges that peace can be discussed outside a mutually agreed legal framework. This involvement also indirectly reinforces the notion that the UN Charter is merely one option, no longer the primary foundation for international relations.

The Indonesian government’s policy is fundamentally problematic. For years, Indonesian diplomacy has consistently emphasized multilateralism and international law—not just as rhetoric, but as a core identity maintained since the dawn of independence.

By engaging in a peace mechanism outside the UN Charter, that position becomes tenuous. How can Indonesia assert its support for a rules-based order while simultaneously normalizing peace negotiated outside the law?

International legal theorists have long warned of the dangers of hegemonic multilateralism. It may appear benign—multilateral on the surface—but it is controlled by one party. The Trump Gaza Board of Peace exemplifies this pattern clearly. The initiative originates from the United States, leadership resides with Trump, the agenda is set in Washington, membership is selectively chosen, financial contributions are the price of entry, and there is no accountability to the UN General Assembly, which is meant to be representing the international community.

If peace is determined by the party who leads, funds, and wields informal veto power, it is fair to ask: Is this a global Board of Peace or merely the Board of America dressed up to appear legitimate?

In international legal theory, the UN is often regarded as a constitutional instrument of the international community. Its Charter is no ordinary treaty; it is the lex superior, the primary framework governing the exercise of power on a global scale. When mechanisms like the Board of Peace operate outside this framework, we witness what Martti Koskenniemi describes as the fragmentation of international law.

This fragmentation is not merely an academic concern; it reflects a tangible reality. Today, one major country forms a Board of Peace. Tomorrow, another could establish a Board of Stability or a Coalition for Order and claim alignment with UN resolutions. In such a scenario, the UN Charter gradually transforms from binding law into mere symbolism—referenced but no longer respected.

Supporters of the Board of Peace will undoubtedly argue that the world needs a quick solution, claiming that the UN is too slow, complicated, and often paralyzed. This argument has some merit. However, international law does not promise speed; it offers legitimacy and accountability.

Peace without a legal framework, even if at first blush it appears stable, is always tenuous from a normative perspective. History has shown that stability without legitimacy rarely endures.

The world is indeed changing, and international law must adapt. The question is whether Indonesia is prepared to build a world where peace is maintained not by law, but by the balance of power alone.

A.D. Agung Sulistyo is a researcher specializing in transnational law and public policy. He has previously worked as a researcher at both the PARA Syndicate and the Soegeng Sarjadi Syndicate.

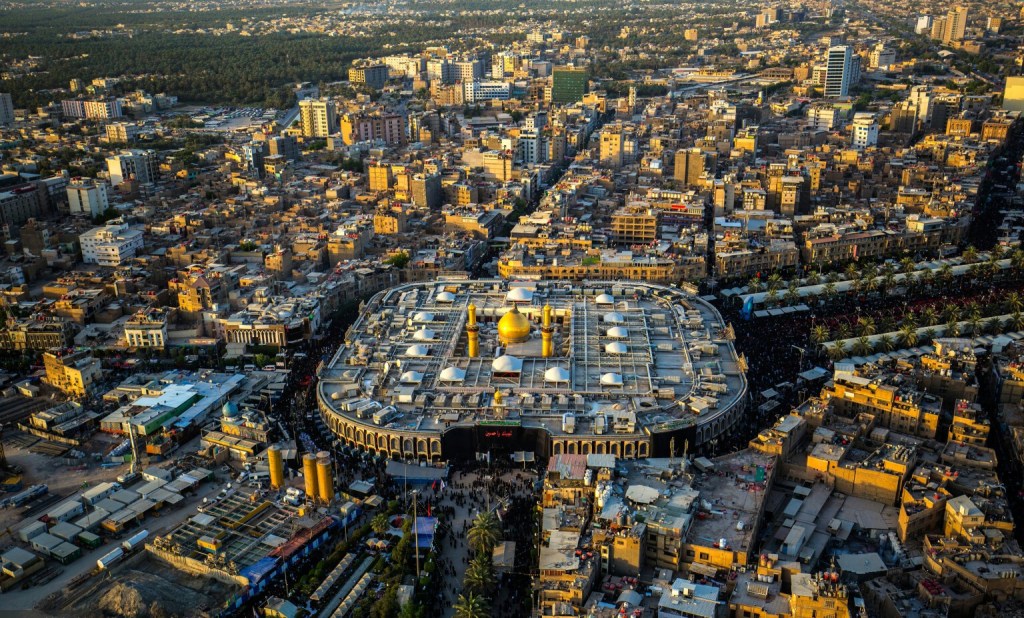

This post is based on https://www.tempo.co/kolom/ilusi-dewan-perdamaian-donald-trump-2111160. Featured image credit: Indonesian homemakers have been front and centre in protests such as this one, in Medan, North Sumatra, against Israel’s war on Gaza, in early December 2023 [Aisyah Llewellyn/Al Jazeera] https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/12/26/we-cry-for-palestine-indonesian-homemakers-mobilise-support-for-family.

- Virdika Rizky Utama. “Indonesia Should Reconsider Decision to Join Trump’s Board of Peace.” Nikkei Asia, 27 Jan. 2026, asia.nikkei.com/opinion/indonesia-should-reconsider-decision-to-join-trump-s-board-of-peace. Accessed 31 Jan. 2026.

- Hendrik Yaputra and Wibowo, E.A. (2026). Soal Dewan Perdamaian, PDIP: Indonesia Harus Bebas Aktif. [online] Tempo. Available at: https://www.tempo.co/politik/soal-dewan-perdamaian-pdip-indonesia-harus-bebas-aktif-2111541 [Accessed 31 Jan. 2026].

- https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2026/2/1/gaza-is-on-its-way-to-becoming-a-semi-protectorate-just-like-bosnia

- https://www.antaranews.com/berita/5443306/dubes-indonesia-perjuangkan-kehadiran-otoritas-palestina-di-gaza

![Indonesian homemakers have been front and centre in protests such as this one, in Medan, North Sumatra, against Israel's war on Gaza, in early December 2023 [Aisyah Llewellyn/Al Jazeera]](https://storiesfromindonesia.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/indonesian-homemakers-protest-in-medan-december-al-jazeera-aisyah-llewellyn.webp?w=770)

Leave a Reply