Sowing Memories Together

By Pujo Nugroho for Project Multatuli, January 21, 2026

The task of preserving the memory of crimes against humanity in Indonesia is a work of silence. The state does not provide a space for it, educational institutions do not teach about it, and society is shaped to distance itself from it.

On Sunday afternoon, September 21, 2025, I went on an outing with nine friends. We set out to visit three mass graves from 1965 in Tlompakan Village, Tuntang District, Semarang Regency.

Suradi and Sugiman, aged 60 and 87 respectively, joined us on our journey. Both were local residents—Suradi was a cemetery caretaker, while Sugiman was a witness to the crimes against humanity that took place six decades earlier. They shared insights about the social and political situation at the time, as well as about the massacres that led to the mass graves.

Sugiman remembers vividly. At that time, all the villagers were terrified, hiding in their homes during nights often punctuated by the sound of gunfire.

Bella, one of the young people present, was deeply impressed by Sugiman’s story, not only because of what he experienced but also due to the calmness with which he recounted it.

“What sticks in my memory most is how he recounted his 1965 experiences so calmly, maybe because he had reconciled or maybe simply because he wanted to mask his feelings,” said Bella, 22.

“It’s amazing that they survived such a dark time.”

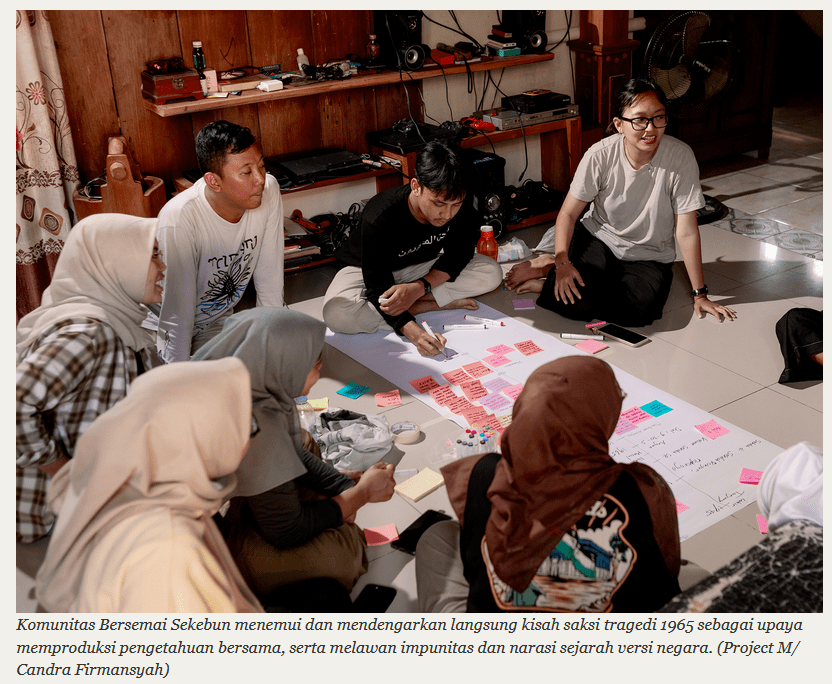

My friends and I at the group of young people in Semarang interested in learning about humanitarian issues named Growing Together (Bersemai Sekebun), every few months regularly go on trips to visit and meet with survivors or witnesses of human rights violations such as this. Throughout 2025, we went on for trips. We call our activity Visiting Flower Gardens.

Visiting Flower Gardens was inspired by Mia Bustam’s care giving practices during her time as a political prisoner during the New Order regime at Camp Plantungan, in Kendal Regency. There she carefully tended to various plants and managed the garden every day.

Caring for the garden wasn’t just a physical activity to pass the time in Camp Plantungan. It was also a way for Mia Bustam to heal and build solidarity with her fellow women political prisoners. In the flower garden, they formed emotional connections, striving to maintain their spirits while living under oppression and suffocating surveillance.

In a similar spirit, Bersemai Sekebun initiated the idea of Visiting Flower Gardens. More than just a historical tour, the activity serves as a space for gathering, building empathy, and sharing views and reflections about past events.

Memory

The hope is to foster dialogue between the younger generation and those directly involved in past narratives and unresolved human rights violations. Participants are encouraged to ask questions and reflect, understanding that memory is more than just a record. It’s a constantly evolving process that shapes how we interpret life today.

As a youth community, Bersemai Sekebun believes that inter-generational solidarity is one key to preserving memory. Public memory is not just about archives or museums, but rather about how today’s generation connects with the past honestly and openly, with a commitment to the victims.

This is crucial because the violence of 1965 has permeated every aspect of Indonesian society, affecting not only survivors and their families, but also those who had no direct connection to the events.

I don’t come from a family of survivors and initially found it challenging to understand what happened during and after 1965. I often wondered: Why is this issue so sensitive? Why is it so taboo to discuss it?

Moreover, the references I discovered before were mainly books produced under the New Order government, which tended to focus on Jakarta from a military perspective. These books failed to explain that the 1965 crimes against humanity were not just about imprisonment and mass murder, but also about the pogrom to impoverish, the destruction of local communities and knowledge, and the erasure of intellectual networks that have had lasting impacts on subsequent generations.

Everything changed after I became involved in the work of Bersemai Sekebun.

The seed of Bersemai Sekebun emerged in 2019 when four young people set out to document the narratives of 1965 survivors in Central Java. They were Adiyat Jati Wicaksono, Albertus Arga Yuda Prasetya, Alhilyatiz Zakiyah Filaily, and Muhammad Solekhan.

Their efforts resulted in a series of activities including the publication of a zine, an archival exhibition, and meetings between survivors and young people in Central Java province’s capital city Semarang. That’s when I became involved.

After meeting survivors and hearing their stories firsthand, I discovered layers of the narrative that had never been discussed in the books published under the New Order regime or in previous discussions about 1965.

Until now, the focus of discussions has often been on state responsibility and the judicial process. However, through the survivors’ stories, the violence of 1965 emerges as a deeply personal and domestic experience. This allows someone like me, who has no family ties to the victims, to feel connected.

Interdisciplinary Learning

This kind of cross-generational learning is what Bersemai Sekebun continues to strive for. We strive to create a space for survivors and young people to engage in dialogue, listen to each other, and build equal relationships so that both groups can empathize with each other’s experiences.

Survivors and Shared Knowledge

Survivors are positioned not only as sources of information but also as subjects who produce shared knowledge. They are provided a space to tell their stories and express themselves. This approach aims to ensure they feel safe and that their experiences as victims of human rights violations are acknowledged.

At the same time, young people who hear survivors’ stories firsthand gain new knowledge and perspectives on historic serious human rights violations, narratives often dominated by the state and their perpetrators. In addition to fostering a sense of shared destiny and solidarity, these gatherings help the younger generation recognize the persistent patterns of impunity that continue today.

We are not only exploring the tragedy of 1965, but also examining the state sponsored street executions, the so-called mysterious shootings (Petrus) of 1983-1985, especially after Arga and I participated in the Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR) fellowship in 2021.

Our focus is on Barutikung Village in Semarang, which has had to endure long-lasting social impacts due to the stigma attached to it being a “crime village” after the Petrus killings.

Consensual

In Barutikung Village, we encourage residents who have inherited stigma to actively participate in knowledge production activities by allowing them to choose the stories they share. This way they understand that their experiences are not simply collected, but are consciously reproduced and distributed in consensual and reflective ways.

This kind of relationship allows us and the survivors or their families to view each other’s experiences and process them together through the narratives they tell. We consistently record and reflect on any changes that arise following these conversations, both in ourselves and in the survivors.

As listeners to stories of human rights violations, we recognize our obligation to safeguard, care for, and treat these stories as powerful knowledge. Therefore, openness with survivors is crucial—not only to build trust but also as a way for us to remain compassionate.

Every story not only demands to be heard; it also demands justice.

Engaging the Younger Generation

The role of young people is crucial in efforts to end impunity.

The generation born after the Reform Democracy Movement removed the New Order regime in 1998 did not directly experience the violence of the New Order. However, they have witnessed forms of state violence that persist today, and they are increasingly consistent.

At this point, the younger generation, including us, plays a vital role in keeping memories alive and preventing similar patterns of violence from recurring.

Friendship

To reach the younger generation, Bersemai Sekebun often begins through friendships: hanging out, then slowly discussing impunity from close and personal perspectives, without a patronizing tone. We also use social media, especially Instagram, and our website to share a variety of ways of knowing.

Yasin Fajar is one of the young people we have successfully engaged through these activities. He initially saw our post on Instagram about plans for a discussion on inter-generational dialogue about the meaning of human rights. However, he only really became involved after a friend invited him to join a Visiting Flower Gardens trip. The meeting and dialogue with survivors left a profound impression on him.

Never again

“I can build knowledge about human rights violations through the personal experiences of survivors who experienced them firsthand. This knowledge serves as a foundation for ensuring these incidents never happen again,” said Yasin, 23.

As well as social media content, Bersemai Sekebun frequently uses songs, films, postcards, and stickers as mediums for campaigning on humanitarian issues. Our works have also been featured in several exhibitions and a variety of arts events. Through these activities we try to bring human rights issues closer to the everyday lives of many people.

Failed

Collective efforts like Bersemai Sekebun’s emerged because the government has failed to address numerous serious human rights violations. We believe that ongoing conversations about these violations are necessary. From these conversations, we can dismantle the government’s repressive practices and lay bear the power structures maintained for generations.

The work of preserving memory, listening to survivors, and challenging government narratives was never designed to be popular. The government does not provide space for it, educational institutions do not teach it, and society is frequently being shaped to avoid it.

Not everyone is ready to take a stand—not because they do not care, but because the structures we face are designed to keep people at a distance. This silence is no accident; it is also a political product of persistent impunity.

Official history

The small number of people involved in this kind of work reflects how power operates. The smaller the space for alternative memories, the easier it is for the government to maintain its own version of history. When few people care, it is simpler to bury old violence and allow new violence to occur.

This silence illustrates that the politics of memory is not just about the past, but also about who benefits when society forgets. Silence is a sign that the government has succeeded in creating distance between the younger generation and its history of violence.

Family

On a number of occasions, we have encountered survivors who have never even told their children or grandchildren about their experiences. We do not always understood why they chose to share their stories with us instead of their own families.

However, this made us feel that every story entrusted to us must be protected. It is this responsibility that keeps this often-silent work going. When so few people are willing to engage in this space, it becomes even more crucial to maintain it.

The work of Bersemai Sekebun takes on greater urgency in today’s political climate as the current government attempts to reshape the grand narrative of Indonesia’s national history.

Former President General Suharto and associate General Sarwo Edhie, those responsible for the wave of anti-communist violence following 1965, have instead recently been awarded the title of national heroes. This undermines reconciliation efforts and ignores the government’s moral and institutional obligations to acknowledge and correct past mistakes. It also underscores the government’s lack of seriousness in resolving cases of serious human rights violations in Indonesia.

Certainly, as the government continues to produce “official” history to cover up violence, citizens must produce knowledge to uncover it.

This memory must continue to be nurtured.

Pujo Nugroho is a community organizer at Bersemai Sekebun (Growing Together), a group of young people working in Semarang and surrounding areas to document and archive the stories of survivors of human rights violations and facilitate inter-generational learning, including through training, art and archival exhibitions, public discussions, and other creative activities. Pujo is speaking at the Festival of the Margins, Pesta Pinggiran, 24 to 25 January 2026, at the Jakarta Arts Center Taman Ismail Marzuki, Jakarta, https://projectmultatuli.org/pesping-2026/.

This post is based on https://projectmultatuli.org/bersemai-sekebun-merawat-ingatan-pelanggaran-ham-semarang/.

Leave a Reply