Consolidating the Working Class Against Elitist Politics, Project Multatuli

By Amalinda Savirani for Project Multatuli, February 21, 2024

Preliminary counting in Indonesia’s February 14, 2024, legislative election indicates that the prospects for the Indonesian Labor Party to gain seats in the country’s House of Representatives are far from optimistic.

Indonesian General Election Commission figures show the Labor Party has gained 0.63% of the vote, or approximately 1.3 million votes (data as at February 20, 2024, with 58.95% counted).

Below threshold

This figure falls below the current statutory 4% vote threshold, or quota, required to gain seats in the national legislature under the current electoral law.

For a party established just three years ago, aiming to exceed the 4% mark, which would require around 7 million votes, is an ambitious target. For example, the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI), which has participated in two elections, controversially led by the youngest son of outgoing President Widodo, and with the benefit of the president’s high approval rating, is also likely to fail to win legislative seats.

At the same time the Labor Party’s efforts may offer a fresh alternative in the electoral struggle. In the interim tally, the Labor Party’s count has exceeded that of other parties founded only three years ago, such as the Ummat Party, founded by National Mandate Party (PAN) founder, and 1998 anti-New Order regime activist, Mr. Amien Rais, along with the Crescent Star Party (PBB), Garuda Party, and Nusantara Awakening Party (PKN). Also, local vote tallies in industrial regions are showing higher results than the national average, particularly in the highly urbanized and industrialized districts of Tangerang and Bekasi bordering Jakarta.

Urban working poor

The Labor Party has emerged from an alliance of worker groups covering laborers, farmers, fishermen, domestic workers, urban poor, and informal sector workers, including the army of online motorcycle taxi drivers (referred to variously as ojol, ojek or gojek).

The party’s focus has been on welfare issues affecting the working class. During its final campaign rally on February 8, banners displaying party policies such as maternity leave rights for women, pensions, abolition of outsourced labor contracting, internships, and health insurance hung around the Jakarta’s major Senayan Istora stadium.

The party’s primary focus currently is the repeal of Law No. 11/2020 Concerning Job Creation, also referred to as the Omnibus Law, which severely disadvantages workers.

Union involvement

The Labor Party’s participation in the February 14, 2024 national legislative elections marks the culmination of a long journey of union involvement in electoral politics over the past 20 years. Over this time, many union leaders have stood as legislative candidates through a variety of political parties. For example, current Labor Party leader Mr. Said Iqbal once served as a legislative candidate representing the Riau Islands province in the 2009 legislative election.

Organized labor and Prabowo’s Gerindra Party

In 2014, a “go-politics” campaign experiment by labor unions in Bekasi District resulted in two labor figures becoming members of the district legislature (DPRD). In 2019, one union leader, Mr. Obon Tabroni (G-Jabar VII), made it into the national House of Representatives standing for the Great Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) Party of the presumptive winner of the recent 2024 presidential poll Mr. Prabowo Subianto. This year, Mr. Obon is again a legislative candidate for Gerindra Party, having declined an offer to join the Labor Party. Mr. Obon sits on a number of House committees, including the House community affairs committee.

The long game

The presence of labor unions – as well as the Labor Party – in the election represents an attempt to advocate for workers’ rights which have long been overlooked by the established elite parties. Although the journey of labor unions to participate in politics has not yet yielded the result hoped for, their presence has served to consolidate progressive political power in the elections. Efforts such as these are crucial as a stepping stone to developing long-term strategies for the 2029 and 2034 elections.

Defense against injustice

The Labor Party’s presence in electoral political contests goes beyond merely efforts to break through the current statutory legislative threshold requirement. Through the Labor Party the present working class alliance has laid an initial foundation serving as a rallying point, and fostered a collective spirit to continue consolidating progressive parts of the community. Supporting progressive parties is a means of defense against injustice.

Injustice for the working class covers at least five areas.

Rights stripping Omnibus Law

Firstly, there is the passage of Law No. 11/2020 Concerning Job Creation (the so called Omnibus Law). Through this law the government pushed further neo-liberal practices in the labor market by expanding the role of outsourcing in labor hire practices, and extended Fixed-Term Employment Agreements (PKWT) from 3 to 5 years.

Growing informal sector

Secondly, Indonesia’s economic structure continues to undergo de-industrialization with the manufacturing sector’s contribution decreasing from 29% in 2014 to 19% in 2022. The service sector’s contribution to national income continues to rise reaching 52% in 2022. The majority of the service sector is informal and therefore exempt from formal labor regulations, including minimum wages and other basic workers’ rights.

Labor market mismatches

Thirdly, unemployment continues to rise. National Statistics Agency (BPS) data from August 2023 indicates there are 7.86 million unemployed individuals in Indonesia. At the same time, in 2022 Indonesia’s universities produced 1.85 million graduates, and vocational schools produced 1.63 million graduates. However, their skills do not always match the needs of the labor market.

Removal of unions from wage setting mechanisms

Fourthly, labor unions have been weakened further through the enactment of Regulation No. 78/2015 Concerning Wages, which abolished the role of labor unions and the formerly-used tripartite mechanism in the setting of wages. Minimum wage determinations no longer involve the tripartite mechanism, which included the Ministry of Labor, employer representatives, and labor unions. Rather now the current mechanism uses formulas based on national economic growth, and inflation rates, for wage fixing.

Under the tripartite mechanism, labor unions made submissions advocating wage levels based on the decent living wage (KHL) index, compiled through the monitoring of prices affecting workers’ living needs. The trend in wage increases since the enactment of Regulation No. 78/2015, around 2.4% per year, is significantly lower compared to the increases won using the tripartite mechanism that included labor unions.

Digital workers

Lastly, demographic shifts are impacting young workers (Generation Y/millennials and Generation Z), who are more likely to be engaged in the creative sectors and frequently work part-time, and or as freelancers. These jobs lack social security systems from employers. Many of them have established labor unions, including the “Sindikasi” Union.

Distrust in political parties

A portion of the public has lost faith in political parties. Political parties are seen as tools of the elite who prioritize their own interests over the interests of their voter constituents.

Cases of political party corruption have become too common, almost a daily occurrence. Political parties indeed have mechanisms to revoke their members’ mandates once they are in the legislature, but such removals often relate to internal party interests, rather than constituents’ concerns.

Cartel parties

A study indicates that post-1998 democratic reform movement (reformasi) political parties in Indonesia lack clear ideological differences and work programs. All the parties appear the same. This similarity has led some experts to describe the Indonesian party system as a system of cartel parties.

Unlike Indonesia’s first post-independence elections in 1955, which featured five ideological bases for parties—radical nationalism (represented by the Indonesian Nationalist Party, or PNI), communism (represented by the Indonesian Communist Party, or PKI), Javanese traditionalism (influencing both PKI and PNI), modern Islam (represented by Masjumi), and traditional Islam (represented by NU)—the New Order regime banned ideologies other than the official state philosophy known as The Five Principles, or Pancasila. [After wiping out the PKI in the late sixties,] the New Order regime amalgamated the party system, finally leaving only nationalism and Pancasila-aligned Islam. With the overthrow of the New Order in 1998 and the ascendancy of the Reformasi democracy reform movement, ideological variants, particularly Islamic, resurfaced, represented by the Justice Party/Prosperous Justice Party (PKS).

Nationalism in name

Nationalist ideology is often used as a shield against foreign ideological influences and is not necessarily tied to party positions on policies. When the pro-employer so-called Job Creation Law was being debated, only the Islamic Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) opposed it, staging walk outs during the legislative sessions that approved the law. Other parties, with nationalist ideologies of various types, supported the law, including the largest party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) of Megawati Sukarnoputri.

Entertainment venue tax proposal

On other policy areas, such as increases in entertainment venue taxes, parties also lack clear positions regarding their nationalist ideologies. This case became viral when popular performing artist Inul Daratista protested on her social media account. After a meeting with the Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Gen. (Hon.) (Redt.) Luhut Panjaitan, the tax increase was postponed.

Kissing the ring

The chair of the Indonesian Labor Party is often seen engaging with major political parties, including when its leaders kissed the hand of former Central Java Governor and presidential hopeful Mr. Ganjar Pranowo, endorsed by PDI-P, which at the time was still supported by President Joko Widodo.

Support the party, not its president

However, PDI-P is one of the parties that supported the enactment of the Job Creation Law. Internally, there is fragmentation among labor unions. Mr. Andi Gani Nena Wea, one of the Labor Party’s initiators, became part of Mr. Ganjar Pranowo’s campaign team, despite the Labor Party not officially endorsing any of the three presidential candidates. This situation further fuels doubts about party elites. Hence, on social media, statements such as “support the party but not its president” often appear in reference to the Labor Party.

One alternative

In short, the Labor Party was born in the context of high distrust in democratic institutions. However, at the same time what options are available for civil society in the current representative democracy? We need alternative parties with clear programs to fight against injustice. At a time when most civil society groups in Indonesia focus on moral movements that tend to be anti-electoral politics, and progressive elements continue to be disappointed at every election, the Labor Party has becomes one of the alternatives.

Notes on Labor Party Inclusivity

One noticeable aspect of the Indonesian Labor Party’s recent campaign activities has been the limited presence of women in leadership positions within the party. Almost all party leaders standing on stage are men.

In order to become a party of the future, Indonesia’s Labor Party must be inclusive and encourage women’s involvement in a variety of capacities. The requirement for 30% female candidate representation has facilitated female union members’ involvement in the Labor Party’s work.

Support organizations for the Labor Party, such as the Urban Poor Network (JRMK), also encourage marginalized groups to become candidates known as #calegpinggiran (candidates of the margins).

In this regard, the Labor Party has provided a new electoral channel for ordinary citizens and marginalized groups to become representatives. This is highly unlikely for the major parties with their hierarchical membership processes. Research on female candidates in political parties shows that the waiting time for female candidates is longer in older parties than in newer parties like the Labor Party or the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI).

Support for the Labor Party on platforms like X (Twitter) also comes from youth groups, most likely part of the younger generation dissatisfied with elite parties and seeking alternative options. They are supporters outside the traditional circles and base of the Labor Party in the manufacturing sector in industrial areas. They are freelance workers becoming increasingly aware of their rights as workers. Thus, the 2024 elections have expanded the Labor Party’s support base and serve as an asset for long-term party consolidation.

However, the expansion of Indonesia’s Labor Party also requires a commitment to prevent and combat the high incidence of violence against women in the workplace. Only by being inclusive can the Labor Party become a modern party and a reference point for Generations Y and Z.

Amalinda Savirani is a lecturer in the Department of Politics and Government at Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta.

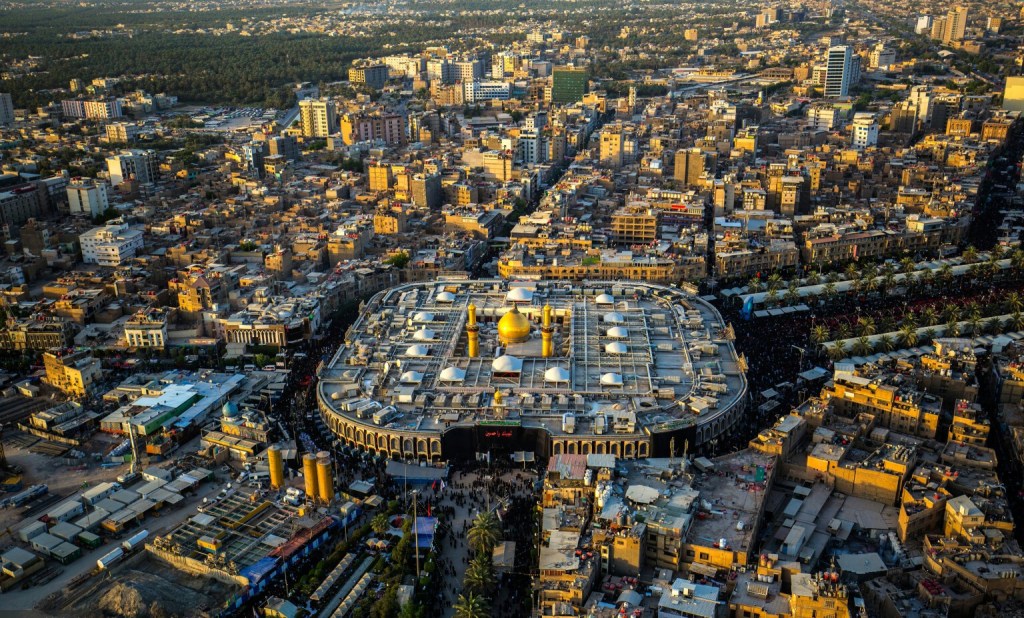

This article is based on https://projectmultatuli.org/konsolidasi-kelas-pekerja-partai-buruh-melawan-politik-elitis/. Featured image credit: Indonesian Labor Party supporters at last election campaign rally on February 8, 2024. Banners showing the party’s program hang from the ceiling of Istora Senayan stadium. The main focus of the party is repeal of Law No. 11/2020 Concerning Job Creation (the Omnibus Law) harming workers. (Labor Party archives)

In related news:

Leave a Reply