Young Jamal, Urban Guerrilla

A Short Story by Mochtar Lubis (1950)

Ever since Jamal quit being an importer I hadn’t seen him once. So when I joined a group of journalists covering the return of the Republican Government to Yogyakarta, I was excited to suddenly run into him at the Kepatihan Office, which Sultan Hamengkubuwono was using as the main headquarters for the restoration of the government. He had grown a beard and mustache. Jamal was the kind of man whose hair and beard grew thick. Although he now looked just like a warehouse guard I once knew called Singh, I kept that thought to myself.

Jamal was carrying a thick folder full of documents.

“So, this is where you’ve been all this time? How did you end up in Yogyakarta? How come you just disappeared?”

I peppered Jamal with questions, but he just grabbed my hand and pulled me a little way from the crowd.

“I got a call in Jakarta for a special assignment in Yogyakarta.”

“How did you make it back into Jogja?”

“Ah, that’s a secret of the struggle,” he said with a knowing smile.

“Oh,” I said.

“I got a job at the Social Affairs Office, which happened to need someone sent to Yogyakarta,” he continued, letting me in on his so-called secret. “I worked there for a month then I quit. Left the office, went underground, joined the guerrillas. Joined the urban guerrillas.”

“What exactly were you doing?” I asked. He looked at me with disdain.

“What was I doing? I was practically a guerrilla fighter. If the boys out there in the countryside were fighting with guns, I was here in the city fighting with my brains. Plenty of others did the same. There were three TNI colonels hiding in the city, not running off to the jungle, fighting here on the inside instead. Dozens of other officers—majors, captains—did the same. And the brave leaders of all the different political parties were carrying on the struggle just as I was. Don’t be so quick to mock other people, you didn’t fight in Jakarta. The only ones fighting were the leaders stuck in Bangka and the guerrillas inside and outside the cities. Even Dr. Sukiman, the Minister of Home Affairs, eventually came into the city and joined our strategy.”

“Ohh,” I said, amazed and admiring. I was the type of person who believed people all too easily.

“But,” Jamal said, laughing, “could you get me a shirt? Doesn’t have to be new, just one of your old ones will do. You understand… you know how it is! Later I’ll tell you all about our urban guerrilla tactics.”

Like I said I was the gullible sort. Hearing that he could tell me about the urban guerrilla fighting I thought this is my chance to get a scoop on the other reporters with an inside story about the resistance. Losing one shirt would be a small price to pay. I could already picture the gripping stories of subversive operations, the dozens of hidden TNI officers, the political leaders who had once shouted about defending independence now proving true to their word staying underground. This would make waves. The story of Dr. Sukiman sneaking into the city, only to be captured too soon by the Dutch and later released, missing his chance to continue the fight because of the signing of the Rum-Royen Agreement. The story of Tejasukmana. So many exciting stories. So I told Jamal to come to my room at Hotel Merdeka that evening. He rushed off, saying he had to meet Brother Tomo—you remember him, the militia leader? Said he’d just come back from guerrilla fighting too.

Then not long after Jamal left, I ran into an old friend outside the Kepatihan Office.

We caught up, swapping stories, and I found out Jamal had been living in the same house as my friend. But when I mentioned Jamal’s back-and-forth one minute working for the Republic, the next for the Netherlands civil authority, his time as an importer in Jakarta, and now his work as an urban guerrilla in Yogyakarta, my friend laughed bitterly. “He’s smart, all right, using Dr. Sukiman’s name, and the names of the Masyumi and PNI leaders, those TNI colonels,” my friend scoffed sarcastically.

“Why are you mad at him?” I asked.

“Ugh, Jamal,” he spat.

“Come on,” I said. “He’s fighting a struggle of subversive, guerrilla-style, inside the city.”

“Ha,” my friend mocked.

“But I believe him,” I argued. “Look at his worn-out clothes. Back in Jakarta, he was always dressed real sharp.” “Ha,” my friend said again. “That’s just for show. Don’t be fooled by those rags. He still has plenty of good clothes at home. He’s been profiteering all this time. When the Chinese business owners lost their nerve and evacuated to Semarang, Jamal cashed in. They sold off all their goods—store stock, sugar, furniture—dirt cheap. That’s Jamal’s idea of guerrilla fighting.” One day Dutch soldiers raided our neighborhood, searching for weapons. Three of them pushed into the house—one was a captain. The moment the captain stepped in, Jamal ran up to him and greeted him like a long-lost friend. ‘Ah, Captain! Please, come in, Captain!’

Can you believe it? He practically welcomed the guy with open arms. Before the captain could say a word, Jamal had grabbed his hand and said, ‘This is my room, Captain. Here are my books, Captain. My wardrobe, Captain. My desk drawer, Captain. Nothing under the mattress, Captain.’ And on and on. ‘This, Captain, that, Captain.’ Until the captain got so bored he left without searching the other rooms. When they were gone, we tore into him. Why had he humiliated us like that, bowing and scraping? Jamal puffed out his chest. ‘You fools! Thanks to my tactics they didn’t search the house! Who says I was scared? I tricked them!’ And he had a point. They hadn’t searched the house. So we just dropped it.”

“Maybe he was just pretending to grovel,” I suggested.

My friend looked at me with scorn.

“And listen to this,” he said. “One day a real guerrilla arrived—an actual TNI major from the countryside. He was hiding in our house while he was in the city. You know what Jamal said, and the guy had been in the house barely two hours?”

“No,” I answered, “you tell me.”

“Young Jamal called me. He pushed me to get the TNI major to leave. I told him he was crazy. We had to help our comrades. It was our duty to help our comrades who were fighting in the towns. Young Jamal was angry and continued to insist. ‘I’m not afraid of getting caught,’ he said, ‘but we have a responsibility as leaders of the people. We need to think of the huge responsibility we have. I’m thinking of your safety, your wife’s, and everyone in the house. If the Dutch find him here we’re all dead. And for what?

But I kept pushing back – Jamal, you’re crazy, I said to him. How can I kick him out of the house even if I am really scared.

You don’t need to be frightened, said young Jamal. Tell the major I’m the one who said he has to leave straight away, for the sake of all our efforts for the struggle. Tell him if he’s caught in this house, he’ll ruin my strategy, me being a guerrilla in the city. Tell him as an officer, as a leader, he should understand his responsibility to the people around him. Jamal kept insisting so I gave in and talked to the major. The TNI major was good about it, and finally he left.

“Oh,” I said.

“Yeah. And don’t believe him when he bangs on about him fighting on the same level as the struggle of Dr. Sukiman, president Sukarno, or vice-president Hatta on Bangka Island, and the dozens of other TNI colonels, majors, and captains in the cities.”

“You sure?” I asked.

“He tells the same stories to everyone,” my friend replied.

After my friend had left, I couldn’t helping thinking about young Jamal. I couldn’t decide whether Jamal was right or wrong. His arguments made so much sense.

He had a good point about his responsibility to tell the TNI major to leave. If I’d questioned him, I can just hear what he’d have said, ‘Didn’t you read the interview with Hatta by the journalists, and what Hatta said to the Working Bureau of the Central Indonesian National Committee?’ he would have said. ‘Why when Sukarno had promised all along again and again to lead the guerrilla struggle, didn’t he go out and join the guerrilla fighters when Jogja was attacked by the Dutch on 19 December last year? In order to protect the life of the president, President Sukarno! What’s the different between Sukarno and me. We are both fighting in our own ways. We’re not military men with the job of fighting. Our duty is to protect our lives so we can continue the struggle for another day. The same as Dr. Sukiman. The same as the leaders of Masyumi and the other political parties. The same as the members of the Working Bureau and the dozens of other TNI colonels, majors, and captains.”

And of course, I wouldn’t have an answer for him. If he believed what he had done was the same as what all those loud-mouthed leaders had done, then who was I to argue?

As I was writing this story, I read a speech by Mangunsarkoro from the Indonesian Nationalist Party gave to a meeting of the Working Bureau of the Central Committee. He said that his party accepted the Rum-van Royen statement as a tactical shift. Because, according to him, our struggle had entered a new phase. His words reminded me of what Jamal had once said back when he was infiltrating Jakarta.

When I questioned him about working with Netherlands civil administration, Jamal told me, ‘In this struggle we have to be able to switch tactics, to adjust our strategy to the changing situation. When it was time for bamboo spears, we used bamboo spears. When it was time to yell ‘Ready!’, we shouted. When it was time to rebel, we rebelled. When it was time to strike we went on strike. When it was time for mass action we held mass meetings. When it was time to fight we fought. And when we could fight no longer, well…we changed tactics yet again.’

Later I bumped into Jamal again at Maguwo Airfield as I was leaving for Jakarta.

“You coming?” I asked.

“Not yet,” he said, flashing that secretive smile, meaning I had to ask.

“What’s going on?”

“Received a new mission—handling the travel papers, luggage, expenses, vaccinations, and arrangements for the members of the delegation and their advisers traveling to The Hague.”

The more I thought about it the more I realized—Jamal was a very smart guy.

*NICA – Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (Dutch: Nederlandsch-Indische Civiele Administratie

Source: Si Djamal Gerilya Kota (Young Jamal, Urban Guerrilla) is a story from the short story collection of Lubis, Mochtar. Si Djamal : dan tjerita2 lain / oleh Mochtar Lubis Gapura Djakarta 1950, p. 45.

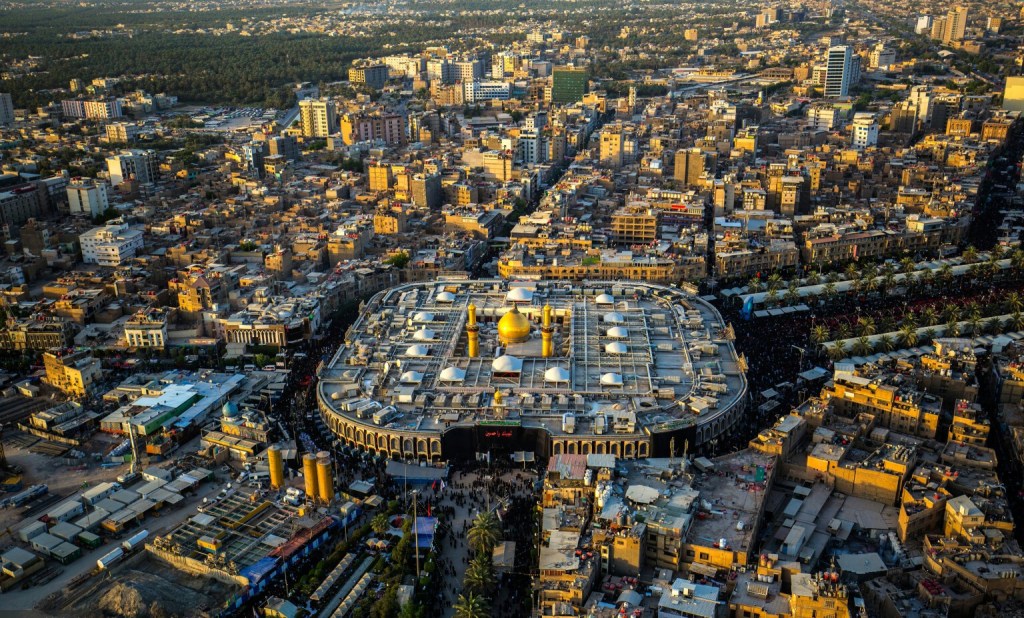

Featured image credit: Drs. Hatta, ir. Soekarno en Hadji Agoes Salim op het vliegveld van Maguwo, korte tijd na het vertrek van Djokjakarta waar ze zijn gearresteerd – http://hdl.handle.net/10648/a8c28f34-d0b4-102d-bcf8-003048976d84 – 19 December 1948