Young Jamal Becomes An Importer

A Short Story by Mochtar Lubis (1950)

“If a man thinks and uses his head, there’s nothing he can’t do,” said young Jamal. We were sitting in a restaurant. I’d run into him at a bookstore, and after he mocked me as usual for only buying detective novels and cowboy stories, he invited me to eat. He was suddenly generous—probably because I promised to read his book, “Philosophy Through the Ages,” written by some author or another, which he said he’d bring over to my house some time.

“So, how’s your plan for modern business coming along?” I asked.

Young Jamal tapped the table. Not something he usually did when he talked. A new habit. Maybe he wanted to make me notice the diamond ring on his finger. Who knew.

“I’ll get to that in a minute,” young Jamal said. “Like I just said, if someone thinks and uses his head, nothing in this world is difficult. People complain all the time—no money, no opportunities, no future, and so on. But they don’t have to be that way. They just need to think a little. Look around—so many job opportunities. Agriculture, livestock, fishing, industry, everything wide open. But our people just don’t want to work. Too lazy to work, and even lazier to think. Shame there’s just one of my brain, and I only have one pair of hands and feet each. Otherwise, there’d be nothing I couldn’t do. Look at me. When I came back down from the mountains, all I had was the clothes on my back. Not a single red cent. But look at me now. New suit, new shirt, new shoes. Diamond ring on my finger, too. Soon I’ll have my own car. I’ve already put in my application for priority allocation. How did I manage all of this? By thinking and working.”

“All true,” I said. “But what’s your new plan?”

He smiled and pulled a folded paper out of his leather bag, laying it on the table.

“This is my plan to start an import-export company. Capital: 200,000 rupiah. A limited liability company. My stake will be a fifth—40,000 rupiah. I don’t have a cent either, but I’ll make it happen. How? Don’t you remember, before I left for Jogja, I lived in that big house on the main road? While I was in Jogja, some of my family stayed there. Now I’ve put it up for lease. Easy. Someone’s already offered 15,000 for the key money. I haven’t taken it yet—holding out for more. Once I’ve got 15,000, the rest is easy.”

“How?” I asked.

“Money finds money. Haven’t figured out the details yet, but it’ll work itself out. If you want in, I’d be happy to have you. Your house would go for 10,000 rupiah. But I’ll be director. You don’t know anything about business, do you? I’ll even find someone who wants to take your house.”

“Where would I live?” I asked.

“Doesn’t matter. Stay in a smaller place for now. In three months, we’ll be able to buy a new house. I’ve checked the trading numbers—guaranteed profit. No risk. Think about it. We put in 40,000. Just from the official sales, we’ll make at least 4,000 a month. In ten months, we’ve got our money back. But if we’re smart”—and he winked—”and know how to squeeze here and there, we’ll make even more. Not much work. Just get the allocation, buy, and resell at the set price. Just go on now and think about it.”

“It’s not that I don’t trust you,” I said, “but I don’t think I’m cut out for business.”

“You’re a true peasant. Just waiting for your Republic’s office to open up again. Rather sit around doing nothing than take control of your own future. Begging for money from your family. You say you hate the NICA*, but you sure don’t mind spending their money.”

I didn’t argue. I was eating the rice he’d bought me, after all. I just nodded.

“Once I’ve organized an office, I’ll let you know. Drop by sometime,” young Jamal said, as we left the restaurant.

“Thanks,” I said. As I was about to leave, he asked where I was going. “Pasar Cikini for a while,” I said. “I’ll go too,” he said, so we rode in a rickshaw together. On the way there, he stopped at a cigarette vendor and bought American cigarettes—three rupiah a pack. The vendor didn’t have change and returned young Jamal’s money. “Do you have any small notes?” Jamal asked me. I gave him three rupiah and we continued on our way. At Prapatan Menteng, he got down. “Here’s your change,” he said, handing me a ten-rupiah note. “I don’t have any more small notes,” I said. “Ah, I’ll pay you back when I come by your house,” he said, and walked off. He took back his ten-rupiah bill. I went home and did the numbers. The cigarettes and rickshaw ride I had paid for was about the same as the meal he paid for me. If this was how Jamal did business, he might actually get rich, I thought.

A month later, I heard about Jamal again. An advertisement in the newspaper. He hadn’t come by my house, probably hoping I’d forget his three-rupiah debt. The advertisement read:

N.V. Gatotkaca Importers/Exporters

Textiles and General Merchandise

Extensive local and international connections

Still under the leadership of: Director Jamal.

And then the address of his office in Kota.

So young Jamal’s plan had worked, I thought. Half regretted not investing my house and going into business with him.

A few weeks after that, I had the chance to drop by his office. Friends were setting up a charity committee to put on a play, and they wanted the program to have advertisements from a few sponsors. Straight away I thought of young Jamal.

His office was in a big commercial building. A marble sign with gold lettering read:

N.V. GATOTKACA

Importers & Exporters

I was convinced his plan had worked. At the very least I’d get a full-page advertisement out of it—two hundred rupiah. I climbed the long staircase, reaching the second attic story. The upper floor was divided among a bunch of businesses, and finally I spotted an arrow pointing to a back corner where N.V. Gatotkaca was set up. From the street I had imagined a huge office—at least a dozen employees working under young Jamal, handling import-export deals, textiles, general merchandise, managing his vast network at home and abroad. But when I got there, I was shocked. His office was just a dingy corner in the attic. A secondhand desk, one chair for him, one for visitors. A wooden cabinet, maybe an old refrigerator repurposed as a safe. No telephone. Young Jamal was leaning back in his chair smoking. He did not look busy.

I called his name twice before he noticed me. He jumped up and smiled.

“Finally, you came,” he said. He must have seen the disappointment on my face because he quickly added, “This is temporary. We haven’t got a phone yet. No vacant office space. The plan is much bigger, but for now, it’s just me. You understand the situation. Want a drink?”

“Iced coffee, if you have it.”

“Wait here, I’ll order some,” he said, going downstairs to a Chinese café across the road. When he got back, he said, “Still don’t have an office boy.”

“New business, I get it,” I said. No point making him mad—I needed his sponsorship.

“How’s business?” I asked.

“Great. But just starting. Not as smooth as planned. Had to bring in some capital from foreigner—Arabs and Chinese. My house only made me 7,000, after bribes, you know. But I’m still director.”

I asked how much money the Arab and Chinese partners had put up. He had no intention of telling me. “Company secret,” he said. But it was easy to work it out. If his stake was 7,000, and the total capital was 40,000, they must have thrown in at least 33,000 rupiah. So what kind of director was he? But I wasn’t going to say anything, after all, I wanted to ask him to advertise.

“So, what brings you here? You didn’t come just to see me, did you?” Jamal asked. Sometimes I thought Jamal was a sharp guy. What he said often hit the mark—like when he said Indonesians were too lazy to work and even lazier to think. And now here he was again. I laughed.

“I have good news,” I said, then explained the charity committee’s plan to stage a play and how we hoped he would help.

“Ah, that,” he said, striking a regal pose as if he was about to grant an audience to one of his loyal princes. “For something like this, of course. Any time. You don’t even have to ask. You know me. Just put my name down. No need for all these questions.”

“Great,” I said. “Really appreciate it. Send over your ad copy, and we’ll run a full-page advertisement.”

“Sure,” Jamal said. I was excited. Two hundred rupiah for the charity.

Then as the office boy from the Chinese café brought in his coffee, Jamal suddenly asked, “How much is a full-page ad?”

“Two hundred rupiah.”

“Two hundred, huh?”

“Oh, hmm, good price, isn’t it.

He kind of went quiet, furrowing up his brow.

“What’s on your mind?” I asked.

“The ad copy,” he said. Finally, he tore a sheet of paper from his notebook and scribbled something on it.

“Just this,” he said, handing it to me. It read:

N.V. Gatotkaca

Still Under The Leadership of: Director Jamal.

“That’s it? A whole page for just this?” I blurted out, immediately regretting it. I had given him the opening young Jamal had been waiting for.

“Yeah, this doesn’t need a full page,” he said quickly. He grabbed the rate sheet and scanned it.

“Look, let’s just make it a sixteenth of a page. Fifteen rupiah.”

“Only fifteen? That’s all you’re donating?” I protested.

“Well, send me ten tickets,” he said. “I’ll buy them at double price. Don’t worry.”

I tried pushing him to buy a bigger ad, but he said that wasn’t necessary, insisting he would contribute in other ways. We nearly argued. As I got up to leave, he asked, “Pay now or later?”

“Now,” I said, annoyed.

Jamal turned to his wooden “safe,” spun the knob, then looked back at me.

“Cashier is closed today,” he said. “I’ll cover it myself.” He handed me fifteen rupiah.

Got no idea either just what he meant by, “cashier is closed today.” Far as I could tell he was president, director, cashier, clerk, and office boy of his company.

As I walked out, Jamal called after me, “Don’t forget to send an invitation. For four!”

And I didn’t reply.

A few months after that, I heard that young Jamal was out of business. They said his Arab and Chinese backers had pulled out, and when the textile allocation was announced young Jamal had no money to buy in. So he closed his business. Maybe it was true, maybe it wasn’t. I haven’t seen him lately. I’ll ask young Jamal next time I bump into him.

*NICA – Netherlands Indies Civil Administration (Dutch: Nederlandsch-Indische Civiele Administratie

Source: Si Djamal Djadi Importeur (Young Jamal Becomes An Importer) is a story from the short story collection of Lubis, Mochtar. Si Djamal : dan tjerita2 lain / oleh Mochtar Lubis Gapura Djakarta 1950, p. 34.

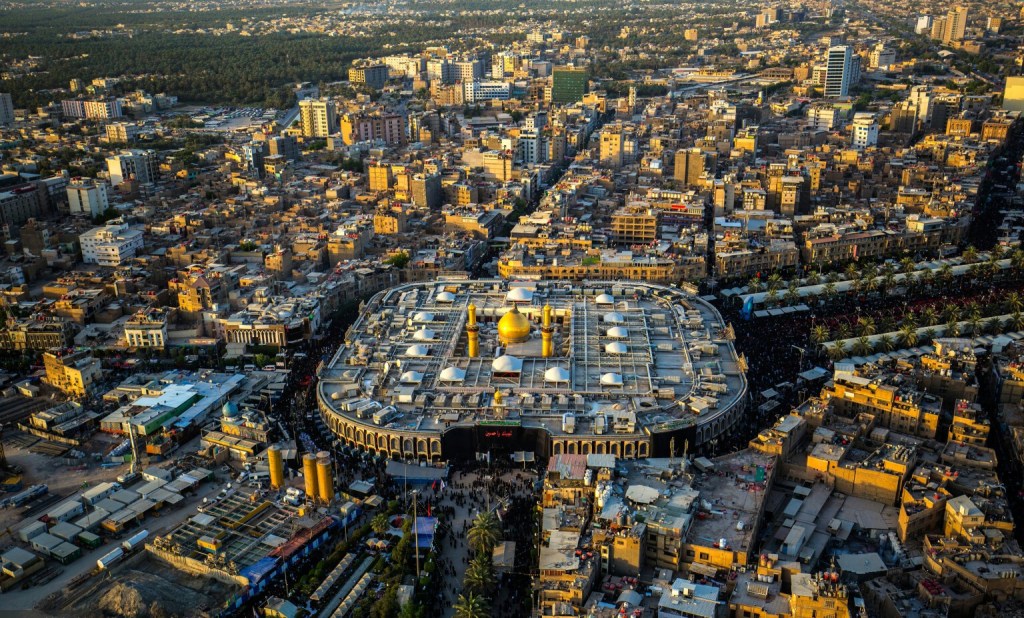

Featured image credit: Collectie / Archief: Fotocollectie Dienst voor Legercontacten Indonesië; Reportage / Serie: [DLC] Beediging; Beschrijving: Gombong: Te Gombong werden 8 KNIL-officieren, ingedeeld bij Inf. V (Andjing Nica) beedigd. Tijdens de eedsaflegging. De nieuwbenoemde officieren (de TLTS. Bolsjes, Kok en v.d. Zee) zijn de eerste naoorlogse leerlingen van de SROI te Bandoeng; Datum: 1948-02; Locatie: Nederlands-Indië; Fotograaf: Fotograaf Onbekend / DLC: Auteursrechthebbende; Permanente url: http://hdl.handle.net/10648/a5722494-0111-452f-c945-e0b2b3a86e95