Art Censorship: “He Wants an Exhibition, He Waits, He Leaves”, from Tempo.co

By Bambang Bujono, curator and art critic, for Tempo.co, December 28, 2024

The recent “shutdown” of a solo exhibition by senior Yogyakarta artist Yos Suprapto at the National Gallery of Indonesia in mid-December 2024 reminds us of the history of art censorship in Indonesia. In this context, censorship is broadly defined, encompassing not only the prohibition of artworks from public display, but also their destruction and similar acts.

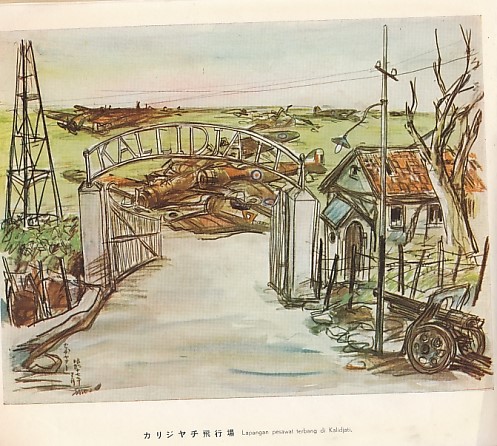

Art censorship in Indonesia can be traced back to the Japanese occupation. During that period, the Japanese established the Keimin Bunka Shidoso, or Japanese Cultural Center (PKJ), in Jakarta in April 1943. One of its activities was opening an art studio where artists could paint and sketch, guided by painters S. Sudjojono, Affandi, and Japanese artists.

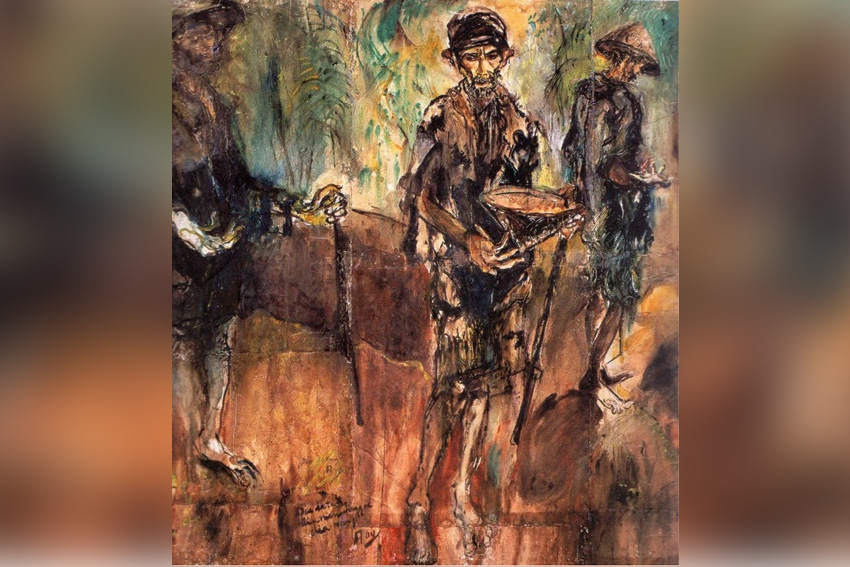

The PKJ organized at least four art exhibitions featuring works from this studio. In the final exhibition in late November 1944, the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police with a secret civilian police unit, were angered by Affandi’s painting titled “He Comes, He Waits, He Leaves.” The watercolor on paper, measuring 41 x 56 centimeters, depicted three scenes of a beggar arriving, waiting, and leaving in sequence. The Kempeitai banned the painting from the exhibition, unwilling to showcase an image of a suffering Indonesia.

The Kempeitai had been monitoring PKJ’s activities since its inception. Their scrutiny extended beyond Affandi’s painting to several sketches by Henk Ngantung, a painter born in Manado in 1921, who later became the Governor of Jakarta from 1964 to 1965. Ono Saseo, a Japanese painter and mentor at the PKJ, encouraged studio participants to create on-the-spot sketches of scenes outside the studio, introducing this method in Indonesia.

A young Henk Ngantung enthusiastically sketched Jakarta’s street scenes, which, according to Mia Bustam in her book “Sudjojono dan Aku” (2006), were filled with destitute individuals suffering from severe hunger. Bustam also recounts witnessing poet Chairil Anwar being beaten by Japanese police, crying out in pain, only to be hushed by Sudjojono, her husband, who cautioned against drawing attention.

Scenes of people in tattered clothing, semi-naked, and emaciated were commonplace in Jakarta, serving as subjects for Henk’s sketches. The Kempeitai, reportedly inspecting the PKJ’s works regularly, tore and burned these sketches. Consequently, Henk Ngantung’s sketches from the Japanese era are absent from the 1987 book “Sketsa-sketsa Henk Ngantung” published by PT Sinar Harapan. Meanwhile, Affandi’s painting of the beggar survived and is now housed in the Affandi Museum in Yogyakarta.

Independence

In the post-independence era, under Indonesia’s first leader President Sukarno—a lover and collector of art since the Japanese period—the art scene flourished. Artists established studios, and the government founded the Academy of Fine Arts in Yogyakarta in 1950. In Bandung, the Balai Pendidikan Universiter Guru Gambar was established, later becoming the Faculty of Fine Arts and Design at the Bandung Institute of Technology. During this time, art censorship was unheard of, though ideological friction among artists existed.

Following the country’s first general elections in 1955, social organizations began serving as tools for political parties to mobilize mass movements, while artists sought “homes” for protection. This led to the formation of cultural institutions affiliated with particular parties or organizations. For instance, the Indonesian National Party (PNI), led by Sukarno, established the National Cultural Institute (LKN) in 1959, headed by writer Sitor Situmorang. Nahdlatul Ulama formed the Indonesian Muslim Artists and Cultural Workers Association (Lesbumi).

The Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) was more advanced, founding the People’s Cultural Institute (Lekra) in 1950, with members including painters Basuki Resobowo, Sudjojono, Henk Ngantung, and Hendra Gunawan; writers like Pramoedya Ananta Toer and Utuy Tatang Sontani; filmmaker Bachtiar Siagian; and musician Sudharnoto, composer of “Garuda Pancasila.” However, internal divisions arose within Lekra, leading to “left” and “right” artist factions, though some remained “independent.”

The spirit of the Gelanggang Seniman Merdeka (Independent Artists Workshop), founded in 1946 by three young artists—Asrul Sani and Rivai Apin, both just 20 years old, and the 22-year-old Chairil Anwar—remained vibrant. It was a spirit rooted in breaking free from the influence of previous generations and rejecting the authority of those they viewed as hypocritical and stifling to creativity. Four years later, the group reaffirmed its position through the “Surat Kepercayaan Gelanggang” (Gelanggang Declaration of Belief), proclaiming themselves as “heirs of world culture.” They rejected ties to Indonesian cultural traditions and instead envisioned the birth of a fresh and dynamic cultural movement.

Despite these frictions, no art exhibitions were shut down or censored. For example, the 1963 art exhibition at Jakarta’s Balai Sidang, held to welcome the Games of the New Emerging Forces, faced harsh criticism from the “left” faction, labeling the artworks counter-revolutionary. However, the government did not intervene, and no artworks were suppressed or subjected to violence.

Cultural Manifesto

Nevertheless, the Manifes Kebudayaan (Cultural Manifesto) group, initiated by several artists in August 1963, faced suppression. Its members included prominent figures such as H.B. Jassin, Trisno Sumardjo, Wiratmo Soekito, Goenawan Mohamad, Soe Hok Djin, Taufiq Ismail, and Nashar.

While debates between supporters and opponents of the Cultural Manifesto were intense, they remained largely civil. However, the climate shifted dramatically in May 1964, when the president issued a decree banning the manifesto. The justification cited was that it competed with the Political Manifesto of 1964, which had been enshrined as the nation’s official ideological framework. Following this ban, manifesto supporters employed in government institutions were pressured to resign, and the distribution of their works was systematically obstructed.

New Order Regime

The putsch staged by the 30th September Movement (G30S) in 1965, attributed by some—particularly the military—to the PKI, led to the party’s dissolution. This period saw not just censorship, but the destruction and burning of artworks by artists deemed to be affiliated with the PKI. Notably, the Bumi Tarung Studio in Yogyakarta was destroyed, and when Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) and the Jakarta Arts Council (DKJ) were established in November 1968 by Governor Ali Sadikin, no “leftist” artists were included.

(A planned performance at TIM was stopped in 1969 intending to to perform “Subali-Sugriwa,” a Kecak dance drama that delved into the tragic brotherhood clash in the Ramayana epic. Officials claimed that the performance could provoke “unwanted sentiments” among the audience, as the themes of betrayal and familial conflict could be misinterpreted as allegories to Indonesia’s then-political climate, still reeling from the aftermath of the G30S insurrection.)

Over time, tensions among artists, whether inside or outside Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM), began to subside. Divisions such as “us” versus “them” gradually faded, and performances across various art forms proceeded without significant issues—though not without exceptions. One such incident occurred in 1972, during the Pesta Seni Rakyat (People’s Art Festival). A group of cak dancers from Teges, Bali, had already boarded their bus and were en route to TIM when they were abruptly stopped and prohibited from continuing by Bali’s cultural advisory body, which reported directly to the governor.

Additionally, several other performances were halted—not by TIM itself, but by government intervention.

In the visual arts sphere, controversies were minimal, until the emergence of the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru Indonesia (New Indonesian Art Movement) exhibition in 1975. Even then, the so-called contentious works primarily sparked debates between artists and art critics rather than any formal action. However, one incident of censorship by Ali Sadikin, the then-governor of Jakarta, stands out—though it turned out to be a case of misinterpretation.

This incident took place during an art exhibition for the opening of Taman Mini Indonesia Indah (Beautiful Indonesia in Mini Theme Park) in April 1975. While inspecting the exhibition before its official opening, Governor Sadikin stopped abruptly in front of a painting and, in a burst of indignation, scribbled on it with a pen, writing, “Sontoloyo!! What is this? An advertisement for Japanese goods?” He then signed his name beneath the comment.

The painting in question was Air Mancur (Fountain) by Srihadi Soedarsono. It depicted the fountain in front of the iconic Hotel Indonesia surrounded by billboards advertising Japanese products. While the advertisements were part of the scene, they were far from prominently displayed. Sadikin’s reaction stemmed from a misreading of the painting’s intent.

The Jakarta Arts Council later clarified to Governor Ali Sadikin that the painting was, in fact, a critique of the growing prevalence of Japanese goods in Indonesia. The context was tied to a larger wave of discontent that had culminated in student protests on January 15, 1974. These demonstrations, aimed at rejecting Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka’s visit—a symbol of Japan’s economic dominance in Indonesia—ended in violent riots that came to be known as the Malapetaka Limabelas Januari (Malari Tragedy).

Upon understanding the painting’s intent, Sadikin apologized to Srihadi Soedarsono. The painting, complete with Sadikin’s scribbled remarks, has since become part of Srihadi’s personal collection. The celebrated artist passed away in February 2022.

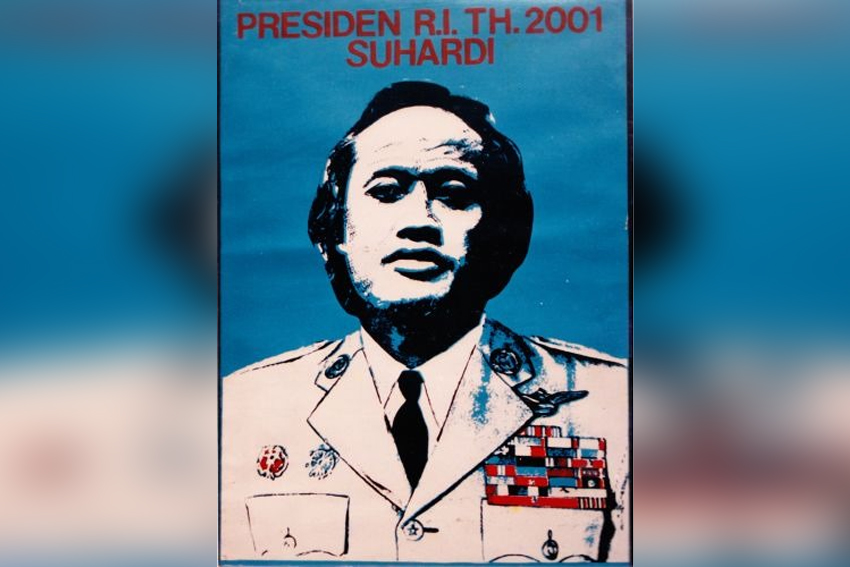

Government censorship reemerged in the late 1970s. At the Seni Rupa Seniman Muda (Young Artists Fine Art) exhibition in 1979, authorities seized a silkscreen print by artist Suhardi. The work was a self-portrait depicting himself in military uniform, accompanied by the text “President of the Republic of Indonesia, 2001, Suhardi.” The provocative nature of the artwork led not only to its confiscation, but also to Suhardi’s arrest at the Jakarta Garrison headquarters for several days.

Thanks to the intervention of Vice President Adam Malik, Suhardi was eventually released. Ironically, the artwork titled President of Indonesia 2001 gained widespread recognition and became iconic, with even the National Gallery of Indonesia acquiring a copy—though it remains unclear which edition of the print they obtained.

Marsinah

Censorship in the visual arts seemed to diminish afterward, with one notable exception: the prohibition of the Art Exhibition for Marsinah in August 1993 by the South Surabaya City Police. Organized by the Surabaya Arts Council, the exhibition was meant to honor the struggle of Marsinah, a factory worker at PT Catur Putra Surya in Sidoarjo who was abducted, tortured, and murdered on May 8, 1993.

Eight company executives, including the owner, Yudi Susanto, were arrested and sentenced to prison for their alleged involvement. However, the Surabaya High Court and the Supreme Court later acquitted the defendants, citing insufficient evidence of their involvement. This outcome fueled suspicions of security forces’ complicity in the case, leaving Marsinah’s murder unresolved and labeled a cold case or “dark number”—a crime left unsolved and shrouded in ambiguity.

The police justified banning the exhibition on the grounds of lacking a permit and touching on a politically sensitive case in East Java. However, the Surabaya Arts Council contested this, arguing that they had never been required to obtain permits for exhibitions since the 1970s, and no prior exhibitions had ever faced such scrutiny.

Reformasi Democracy Reform Movement and Current Government

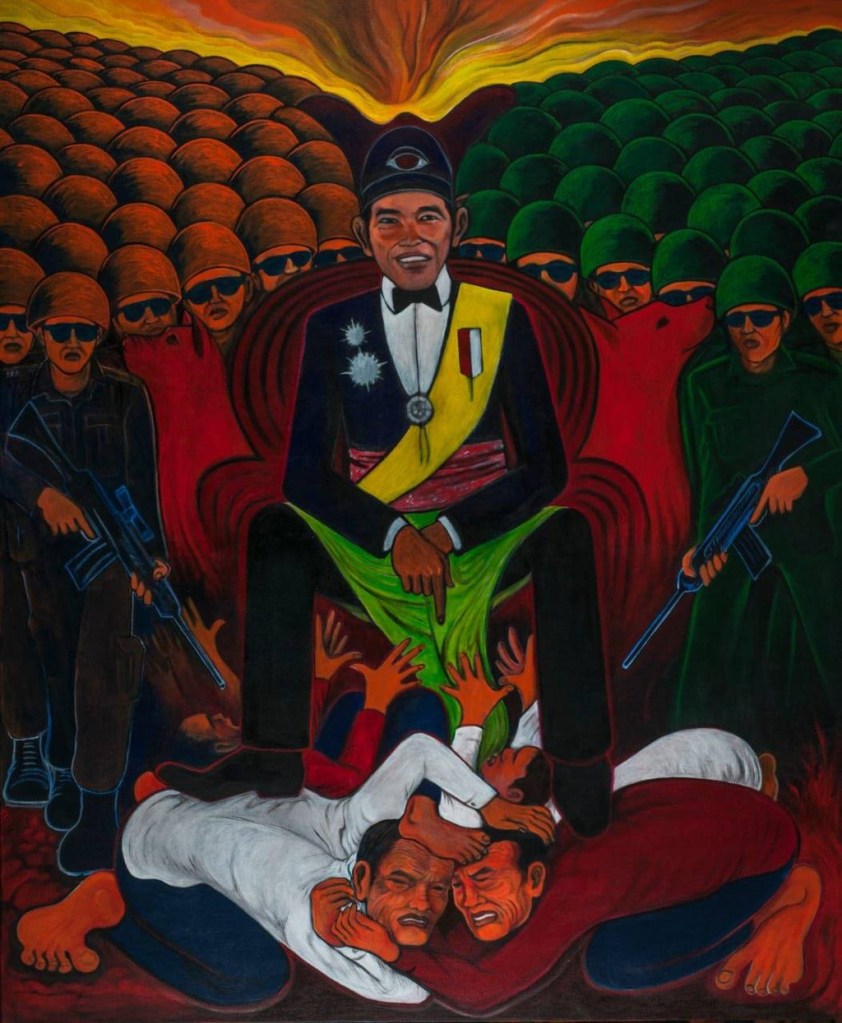

Since the success in 1998 of Indonesia’s democracy reform movement (Reformasi), the first instance of censorship in the visual arts occurred in December 2024 during President Prabowo Subianto’s government.* The National Gallery of Indonesia and the Ministry of Culture canceled the exhibition “Awakening: Land for Food Sovereignty,” which was set to feature paintings and installations by senior Yogyakarta artist Yos Suprapto. The National Gallery claimed that certain paintings did not align with the exhibition’s theme and lacked approval from curator Suwarno Wisetrotomo, who subsequently resigned in protest.

Minister of Culture Fadli Zon claimed that some of Yos’s works contained political undertones, potentially interpreted as “insults against a (certain unnamed) individual (former president).” He also referred to concerns about depictions of nudity and explicit sexual scenes, which he thought inappropriate.

While censorship of the visual arts in Indonesia remains relatively rare, it persists under various regimes. Since the Japanese occupation, the reasons for such bans have varied widely. However, a consistent theme emerges: the public is often denied access to these works, or they are swiftly removed from display. In some cases, artists themselves have faced arrest over their creations.

This article is based on reporting by Tempo.co at https://www.tempo.co/teroka/sensor-seni-rupa-hingga-zaman-prabowo-1186943.

Notes: *In 2012, Indonesian artist FX Harsono‘s poignant works addressing the 1998 anti-Chinese riots faced resistance during their showing at a private gallery in Jakarta. Harsono’s art, which highlighted the erasure of ethnic Chinese narratives in Indonesian history, was seen by some nationalist groups as “divisive.” Threats of protests and violence forced the gallery to tighten security and eventually withdraw several pieces. Another example of Harsono’s works is Gazing on collective memory 2016.

In earlier news…

Artist Yos Suprapto Exhibition at National Gallery Canceled

By Tempo.co | December 20, 2024

JAKARTA—The National Gallery of Indonesia abruptly canceled the solo exhibition of Yogyakarta-based senior artist Yos Suprapto, titled “Reawakening: Land for Food Sovereignty,” mere minutes before its scheduled opening on Thursday evening, December 19, 2024. Visitors arriving at the venue found the glass doors locked and the lights turned off, despite the exhibition being slated to run from December 20, 2024, to January 19, 2025.

Around ten minutes before the scheduled opening, Tempo Magazine received a press release from the National Gallery’s public relations team announcing the postponement. “With great regret, we inform you that the opening of Yos Suprapto’s solo exhibition ‘Reawakening: Land for Food Sovereignty,’ originally planned for this evening, December 19, 2024, in the Multipurpose Hall, has been postponed due to unavoidable technical issues,” the statement read.

Artist Blames Censorship for Cancellation

According to Yos Suprapto, the exhibition’s cancellation stemmed from a demand by curator Suwarno Wisetrotomo, appointed by the National Gallery, to remove five of the 30 paintings from the exhibition. These pieces, Yos claimed, referenced a prominent Indonesian figure. When the artist refused, he decided to cancel the exhibition entirely and return his works to Yogyakarta. “I no longer wish to work with the National Gallery or the Ministry of Culture,” Yos declared in a statement.

Although the audience could not view Yos’s works, the event continued with a speech by artist and filmmaker Eros Djarot, who expressed disappointment over the sudden cancellation. “This reflects an excessive fear on the part of the curator,” said Eros.

Curator Resigns Amid Dispute

Suwarno Wisetrotomo resigned as curator, citing disagreements over the inclusion of two specific artworks. Suwarno stated that the exhibition’s agreed-upon theme, “Reawakening: Land for Food Sovereignty,” had been well-researched and developed by Yos, including an installation featuring soil and paintings. However, he believed two paintings expressed overly blunt criticism of political power, undermining the exhibition’s intended focus.

“The works sounded like outright rebukes—too vulgar and lacking the metaphorical depth that art uses to convey perspectives,” Suwarno explained. Despite Suwarno’s objections, Yos insisted on including the pieces, leading to protracted disagreements since October. Suwarno ultimately resigned but emphasized that his decision was not meant to halt the exhibition. “As a curator, it’s my responsibility to ensure alignment between the exhibition’s theme and its content, and my perspective should matter in that process,” he said.

Artist Accuses Gallery of Censorship

Yos described escalating tensions, beginning with Suwarno’s suggestion to cover two of his paintings, Konoha I and Konoha II, with black fabric—an idea he reluctantly accepted. However, hours later, National Gallery representatives demanded that three additional works also be concealed. “I call this censorship,” Yos said on Friday, December 20, 2024.

National Gallery Defends Its Decision

Jarot Mahendra, Head of the National Gallery, explained that some works displayed in the exhibition space had bypassed the agreed-upon curation process. “Following an evaluation by the curator, these works were deemed inconsistent with the curatorial theme,” Jarot said. He added that mediation efforts between the artist and curator failed, leading the gallery to postpone the exhibition to preserve its thematic integrity.

“We aim to facilitate further communication between the artist and the curator to resolve this issue,” Jarot stated.

Artist Demands Compensation

Yos warned that the National Gallery must compensate him for the postponement, citing significant financial losses, including the costs of accommodating international guests. “I’ve incurred tens of millions of rupiah in expenses,” he said. “I’m giving them until this evening to resolve the matter; otherwise, I’ll withdraw my works and return to Yogyakarta.” Reporting by Dian Yuliastuti and Seno Joko Suyono.

This post is based on https://www.tempo.co/teroka/pameran-yos-suprapto-di-galeri-nasional-diberedel-1184010. Photo credit Kumparan.com.

In related news:

- https://indoartnow.com/artists/yos-suprapto

- https://tangsel.jawapos.com/news/2505443399/foto-foto-lima-lukisan-karya-yos-suprapto-yang-diberedel-galeri-nasional-jakarta-diduga-mirip-wajah-jokowi

- https://www.detik.com/pop/culture/d-7700624/lukisan-lukisan-yos-suprapto-di-gni-akhirnya-resmi-diturunkan

- https://m.kumparan.com/hidayat-adhiningrat1500207974176/konoha-telanjang-di-pameran-yos-suprapto-249KDqp0170/full

- https://megapolitan.kompas.com/read/2024/12/20/22160841/pameran-tunggalnya-ditunda-seniman-yos-suprapto-ada-kekhawatiran-dari

- https://www.kompas.com/tren/read/2024/12/20/144625265/profil-yos-suprapto-seniman-yang-gelar-pameran-tunggal-di-galeri-nasional

- https://www.tribunnewswiki.com/2024/12/20/yos-suprapto

- https://storiesfromindonesia.com/2017/09/03/book-review-black-december-1974/

- https://storiesfromindonesia.com/2019/09/26/visual-arts-contemporary-worlds-indonesia-at-the-nga/

- https://archive.ivaa-online.org/events/detail/14

- https://archive.ivaa-online.org/khazanahs/detail/3808

Leave a Reply