Presidential Election 2024: The Return of New Order-Style Elections

By Made Supriatma for Project Multatuli, February 20, 2024

Certain people are making a lot of noise at the moment raising questions about vote-counting fraud. And even though there may have been fraud during the voting, it is unlikely to have changed the actual result of the vote count.

People are also questioning the quick count. Some accuse polling organizations of manipulating their polls to influence public opinion. I don’t know why accusations like these are appearing. As someone who studies political science I believe it is possible to estimate general election results using quick calculations, and their accuracy can be defended too.

Even so, this does not mean that the 2024 election was honest, fair and met democratic expectations and standards. I came to this conclusion after observing the nomination, campaigning and voting processes. It has to be admitted that there was fraud during both the voting and vote counting.

There are people who have taken advantage of the situation to get individual candidates up, whether in the legislative, presidential or senatorial elections. This has been widely discussed at the community level, though it won’t have a significant impact on the overall election result.

So, what is it that makes this election so tainted, and even makes it the election to date closest in style to a New Order election?

If we look at the results of the 2024 general election, people were surprised because the election was over in just one round. Not only did the candidates Gen. (Retd.) Prabowo Subianto and running mate Mr. Gibran Rakabuming Raka (President Joko Widodo’s eldest son) receive more than the 50% needed to win in one round (and avoid the need for a run-off second round election), reputable polling organizations predicted quick count results from 56 to 58%. If this was true, it would mean that Prabowo-Gibran’s vote was slightly higher than the vote received by President Joko Widodo and running mate Mr. Ma’ruf Amin in the 2019 election where they received 55.50%. At the same time, the two other candidate pairs, Mr. Anies Baswedan and Mr. Muhaimin Iskandar (endorsed first by the National Democrat Party, or Nasdem Party, of media magnate Mr. Surya Paloh) and Mr. Ganjar Pranow and Mr. Mahfud MD (endorsed by PDI-P) who were only gaining predicated votes ranging between 24-25% and 16-17% respectively.

So what happened?

Why are Prabowo-Gibran so dominant? Why are Ganjar and Mahfud projected in the preliminary results to not win a single province? Meanwhile, Anies Baswedan leads in Aceh, West Sumatra, and Jakarta.

These results are particularly poor for Ganjar and Mahfud. The pair even lost in Central Java, the province Ganjar Pranowo led for two terms as provincial governor (2013-2023). In this province in recent election, Ganjar only won in two districts, Boyolali and Wonogiri. Ganjar even lost in his hometown district, Karanganyar. The share of Ganjar-Mahfud’s vote in Central Java currently stands at only 33-34%. Meanwhile, in Yogyakarta, they only managed to achieve 28%.

The share of Ganjar’s vote in Central Java is significantly lower than in 2018 when he was elected governor for his second term. At that time, Ganjar received 58.78% of the vote. However, this achievement still pales in comparison to Joko Widodo who swept Central Java in the 2019 presidential election with 77.29%, leaving Prabowo with only 22.71%.

But there is another side to these preliminary results. The results of the vote for the provincial and regional legislatures (conducted simultaneously) indicate that the configuration of political party strength remains the same as in the 2019 elections. There are also indications (though this awaits the announcement of the official result from the General Election Commission) that dynastic candidates will dominate the legislatures at both the national and regional levels.

Presidential vote was not the same as the legislative votes

From the result of the 2024 elections, it can be concluded that the so-called coattail or down-ballot effects did not eventuate. This means that presidential choices was not the same as legislative choices. Similar to 2019, there was an assumption that the vote for the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) increased because of Joko Widodo’s candidacy. The choice of Joko Widodo was bundled with a choice for the PDI-P.

In the 2024 elections, at least in the provinces of Central Java and Yogyakarta, which I closely observed, the PDI-P vote appears to have been relatively stable. It can be expected that PDI-P will once again become the strongest party in Central Java province, with its share of the vote remaining largely unchanged.

Battleground

The 2024 elections highlight Java as the main battleground. In West Java and Banten provinces, it appears that Prabowo’s vote has not changed significantly compared to 2019. These provinces are Prabowo’s strongholds. However, the real battleground has been in Central Java and Yogyakarta provinces.

With no coattail effect, and party votes remaining stable in the legislative elections, it is clear that the Prabowo-Gibran campaign, significantly assisted by President Joko Widodo, targeted Ganjar-Mahfud. Despite public appearances, and online rhetoric suggesting a tight race between the two camps, on the ground, at the grassroots level, forces were mobilized against Ganjar-Mahfud.

“Mr. 25%”

This tactic makes sense. In various preference, or so-called electability, polls, Anies-Muhaimin’s electability rating never exceeded 22-25%. Anies can be called “Mr. 25%.” National quick count results also indicate that Anies-Muhaimin will receive around 25% of the vote.

The remaining vote share for Prabowo-Gibran and Ganjar-Mahfud was 75%. So it makes sense that the road to the Independence Palace was going to need the majority this three-quarters of the voter. It turned out that Ganjar-Mahfud was indeed the target of a Prabowo-Gibran operation, and especially by President Joko Widodo. Ganjar-Mahfud had to be completely defeated in areas where they has the potential to be strong.

Data shows that Ganjar and Mahfud significantly under-performed in North Sumatra (receiving around 12-13% of the vote; whereas Joko Widodo won with 52.3% in 2019), the entire Java region, Bali, and East Nusa Tenggara provinces. These were operational pockets for mobilizing voters for Prabowo and Gibran.

The power of incumbency

President Joko Widodo played a major role in eroding support for Ganjar and Mahfud. As a president openly supporting Prabowo-Gibran, Joko Widodo wielded the “power of incumbency” for Prabowo and Gibran his eldest son.

One of President Joko Widodo’s targets was Central Java and Yogyakarta provinces. From my records, President Widodo spent nine days in these two provinces during January 2024. He was busy distributing handouts of social welfare food packets, and inaugurating whatever he could. He traversed the Central Java region from north to south, east to west.

The bureaucracy, police and military

The power of incumbency was accompanied by the involvement of the civil bureaucracy, police, and military personnel. From a variety of interviews, it was common practice to steer civil servants towards voting for Prabowo-Gibran. Local police and military personnel kept and eye on district heads, especially those from PDI-P.

In PDI-P strongholds, campaigns were conducted discreetly with the slogan, “We are PDI-P, We are Jokowi, We are Prabowo.” This reality is confirmed by Prabowo-Gibran supporters who claim that this was a ‘silent operation’ to win for Prabowo-Gibran. It makes sense that this was conducted discreetly, accompanied by security and intelligence agencies, even though democracy usually always emphasizes transparency, and open discourse.

The effects of the power of incumbency exercised by President Widodo through social welfare food handouts, and a variety of policies such as increasing pension allowances for three months, and raising the salaries of civil servants, police, and military personnel by 12%, had a major impact.

Furthermore, the mobilization of government agencies was highly effective in building support for Prabowo-Gibran. This mobilization extended down to the village level. Policies to extend the term of village heads also had a significant impact.

Corruption as political blackmail

What was also apparent was the use of corruption investigations as political weapons. Neutral or non-supportive local officials were promptly dealt with. In November 2023, all the village heads in Karanganyar District, Ganjar Pranowo’s home town, were summoned to District Police Headquarters for questioning about allegations of the misuse of regional budget funds. Sidoarjo District Head, Mr. Harta Muhdlor, started campaigning for Prabowo-Gibran immediately after being summoned by the national Corruption Eradication Commission. The same goes for East Java Governor, Ms. Khofifah Indar Parawansa.

The results of these operations were highly effective and were even felt by PDI-P candidates in a variety of area. They did not dare to campaign for Ganjar-Mahfud, because they knew that to do so would ruin their own campaigns.

Safety First

Many of Ganjar-Mahfud’s campaign materials piled up in the homes of PDI-P candidates. A PDI-P candidate admitted to me, “What else could I do? If I campaigned for Ganjar-Mahfud, my own campaign was all over!” Elsewhere, I found PDI-P candidates quietly campaigning for Ganjar-Mahfud. “What mattered was being safe,” they said.

With such mobilization, it’s no wonder that the PDI-P vote remained relatively unaffected. So the anticipated political battle between President Widodo and PDI-P which had been predicted by many political observers did not materialize.

As we know, as well as supporting Prabowo-Gibran, President Widodo also positioned his (other) son to acquire a small party, the Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI). PSI targeted exceeding the statutory legislative threshold in order to gain seats in the legislature (requiring a minimum threshold of 4% of the national vote). However, this plan seems to have been canned because of the high risk of leading to direct confrontation with PDI-P.

Waking the sleeping bull

In 2019, Prabowo chose a strategy of direct confrontation with PDI-P and President Widodo in Central Java province. This included relocating his national campaign headquarters to President Widodo’s home town of Solo in Central Java. The result was dismal. It was like waking a “sleeping bull,” as described by one friend who wrote an article on the issue.

What were the strategic steps taken by President Widodo in not disturbing this “sleeping bull”? In my view, President Widodo wanted to reconcile with PDI-P and its chairwoman former President Megawati. He would be able to argue that he did not intend to destroy PDI-P, that he actually wanted to save it as a powerful party, that he only wanted Prabowo-Gibran to win, not to provoke PDI-P.

This strategy was crucial because after the elections the political dynamics will change. The elites will bargain and decide who gets what. With a one-round election, President Widodo’s position will undoubtedly be strong. He has won twice against Prabowo, and he can argue that Prabowo wouldn’t have won without his help. However, the problem then becomes will Prabowo accept being under (former President) Joko Widodo’s shadow? We are yet to find out the answer to this question.

One thing is clear from the 2024 elections: they are the closest election yet in style to the elections held under the New Order regime. The misuse of power and incumbency beyond the boundaries of state norms is glaringly obvious. Our democracy is indeed dying. Ironically, its killers are those chosen and honored through the democratic process.

Made Supriatma is a member of the Knowledge Council and Senior Researcher at YLBHI. This article is based on Pilpres 2024: Kembalinya Pemilu Gaya Orde Baru – Project Multatuli and is not authorized.

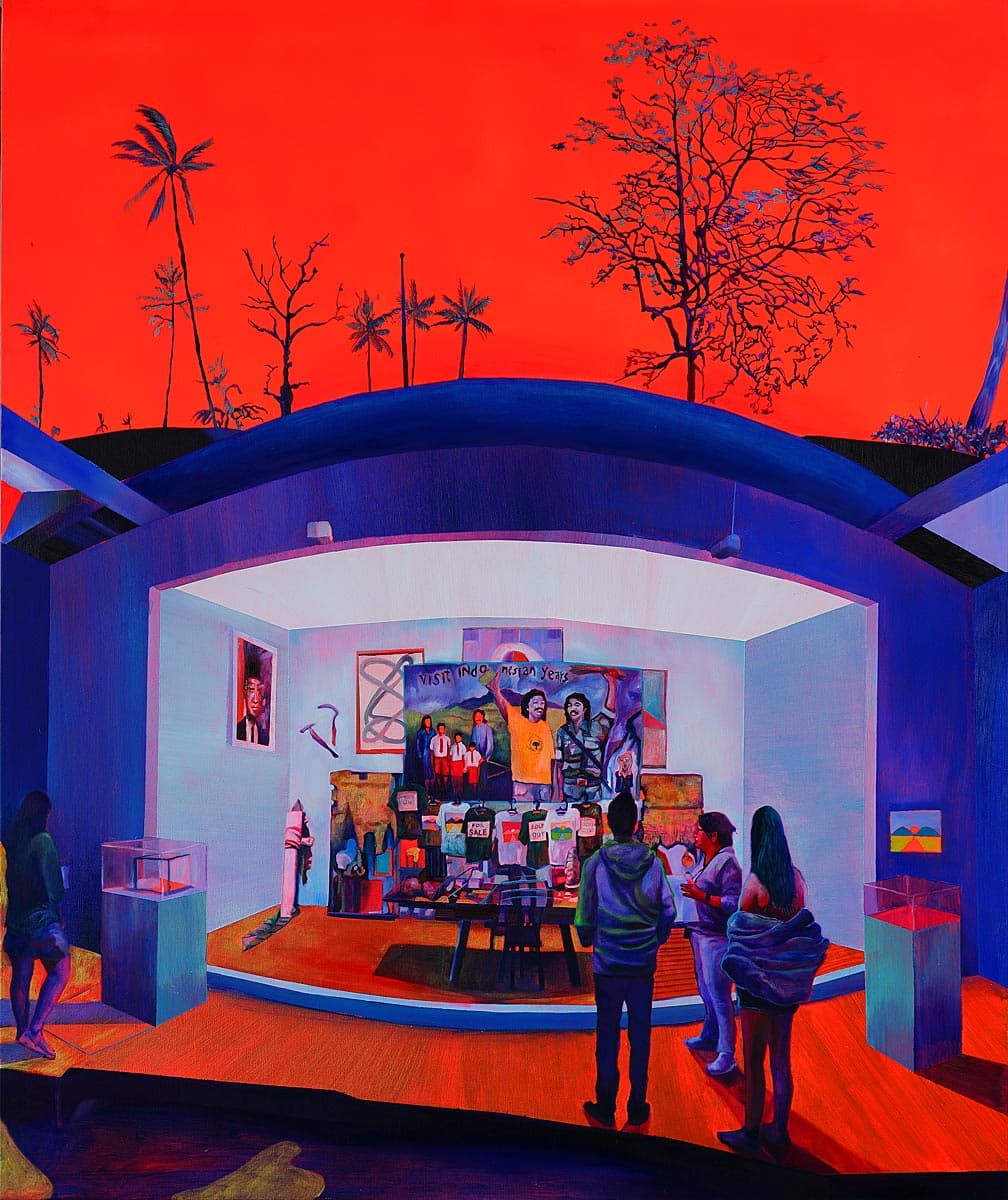

Featured image credit: The stage of earthly delight, Created by Zico Albaiquni, Medium: oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas, NGA 2018 Courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery, Singapore https://digital.nga.gov.au/archive/contemporaryworlds/works.cfm.html; https://digital.nga.gov.au/archive/contemporaryworlds/works.cfm%3Fwrkirn=329029.html

In related news:

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2025/04/21/06064971/fenomena-tentara-kembali-masuk-kampus-dejavu-orba

- https://youtu.be/AWjLiJSZgis?feature=shared

- https://x.com/andreasharsono/status/1844225839229174242

- https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1920038/zulhas-sebut-pemerintahan-prabowo-bakal-mirip-seperti-orde-baru

- https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1859245/mk-minta-penyaluran-bansos-tak-lagi-dilakukan-jelang-pemilu

- https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20240419144305-617-1088127/khofifah-yakin-putusan-mk-bakal-kuatkan-kemenangan-prabowo-gibran

- https://metro.tempo.co/read/1858533/manuver-politik-bupati-sidoarjo-tersangka-korupsi-gus-muhdlor-dari-pkb-dukung-prabowo-gibran-sampai-tak-hadir-panggilan-kpk

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/03/08/21242341/gaspol-hari-ini-adu-kuat-dua-matahari-di-kabinet-prabowo

- https://www.cnnindonesia.com/internasional/20240302073210-106-1069517/pakar-asing-prediksi-risiko-prabowo-jokowi-pecah-kongsi-usai-pemilu

- https://x.com/CNNIndonesia/status/1763747297249178007?s=20

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/02/22/11034211/temuan-komnas-ham-12-dari-14-kepala-desa-di-kecamatan-buduran-jawa-timur

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/02/21/09234511/real-count-sementara-ganjar-mahfud-tak-unggul-di-provinsi-mana-pun-tapi

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/02/21/14103961/din-syamsuddin-pimpin-pernyataan-100-tokoh-tolak-hasil-pilpres-2024-roy

- https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2024/02/21/05594361/wacana-hak-angket-usut-dugaan-kecurangan-pemilu-digulirkan-ganjar-didukung

Leave a Reply