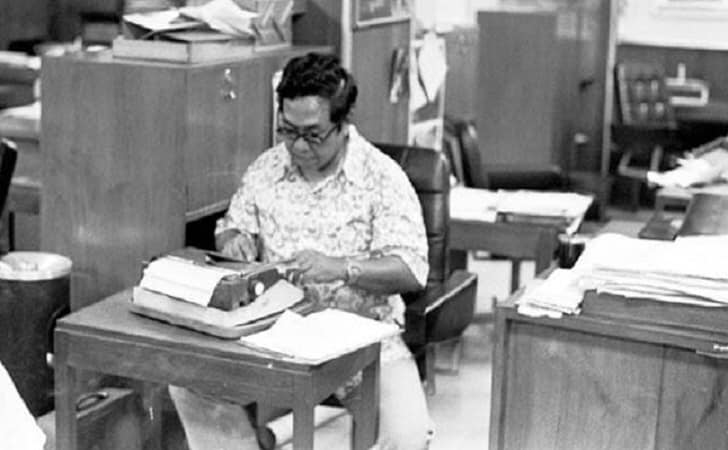

Op-Ed: Why Are They Angry?

By Abdurrahman Wahid1, Tempo Magazine, June 20, 1981

A friend asked me, why do many Islamic religious leaders get angry when they hear the term ‘fundamentalists’2 or take offense when someone discusses the ‘Islamic state’ issue?3

This is a question worth contemplating, because it points to highly complex developments in the lives of Muslims in society. It is also related to the crisis of the cultural identity of Muslims around the world, not only in our country.

Complex questions cannot be answered simply. They require deep reflection and moral courage to see the issues clearly. This involves not being carried away by anger or fears deeply concealed behind the pride in one’s own historical role, or zealously pointing the finger at the ‘other side’ in the political, cultural, and religious issues being addressed.

It also requires the ability to distinguish between areas of life that are genuinely part of the Muslim community’s ‘thought agenda,’ and those that are merely superficial issues being promoted as signs of an Islamic revival.

Self-Adoration

Muslims everywhere can be divided into two main groups: those who idealize Islam as the one and only alternative to every kind of ism and ideology, and those who accept the world ‘as it is.’

The first group believes that Islam has all the answers to humanity’s major problems. They remain only to be fully implemented, without the need to draw from others. Therefore, if one sees a need for dialogue with other beliefs, isms, or ideologies, this should be done within the context of demonstrating the superiority of Islam.

A range of “proofs” are presented – typically by offering idealistic answers that Islam has previously formulated. These answers are normally grounded in a set of idealistic assumptions: if only humanity wanted to follow the teachings of Islam (even though, in reality, they do not), if only leaders would practice Islamic morality (even though only just one person was able to), and so on.

Formal Islamic postulates are presented as responses to the crises of modern life: Quranic verses and Hadiths of the Prophet (SAW) are the only outward measure of the “degree of Islamicness” of everything that should be done.

It is not surprising that critical self-examination cannot be fully developed, because Islam is considered “already perfect.” Therefore, there is a tendency to only glorify oneself, to belittle external developments. Any developments outside of our preoccupation with the greatness of Islam then has no great value.

If external developments cannot be ignored, reasons are sought to avoid thinking deeply about them: e.g., this is a communist idea, that is a secular idea, and so on. The more external reality challenges our perspective, the greater the efforts to escape its concrete realization.

If one presents ideas to find concrete solutions (not just idealistic ones) by applying Islamic teachings to a new framework of thought derived from other isms, beliefs, and ideologies, then accusations of apostasy, disbelief, and (once again) secularism are applied to the proposal itself.

Fortress Mentality

This leads to what some observers have called a “fortress mentality”: Islam has to fence itself off tightly from the infiltration of ideas that might damage its purity. Without knowing it, this mindset actually represents an implicit acknowledgment of Islam’s weakness. Isn’t closed-mindedness only a testament to the inability to sustain one’s existence in openness? Doesn’t isolation in fact indicate a weakness in interrelating?

When this psychological disposition is accused by outsiders of containing fundamentalism, or of still entertaining the idea of an ‘Islamic state,’ clearly it provokes anger as a reaction. Isn’t it because of the fear of outside ‘negative influences’, that it then leads to suspicion of all opinions from ‘outsiders’ about themselves? Isn’t sensitivity the result of an attitude of locking the door like that?

However, the labeling as fundamentalists does not apply to all Muslims who idealize Islam and consider it the sole alternative to all the existing isms, beliefs, and ideologies.

A significant number of idealistic Muslims can accept the presence of other isms, and see the role of their religion as functioning to direct these isms for the essential needs of humanity, whether it be nationalism, socialism, and so on. There are many Muslim idealists who see the formal ideology of the state as a regulator of political relations, while Islam functions mainly in sociocultural relations. Clearly not all Muslim idealists are fundamentalists. If so, why are almost all ‘Muslim idealists’ angry at the term above, or at the notion that there still exists aspirations to establish an ‘Islamic state’ and such like?

Because they have locked themselves in a mental fortress of their own making. All labels of “external” then are regarded as applying to everyone within the fortress, as a gratuitous accusation and prejudice towards all idealistic Muslims who are inside the fort. Their method of thinking is to simplify problems with the result that the application of any name they find unsympathetic is thought of as a threat.

It has far-reaching implications indeed for the future development of Islam. Nevertheless we don’t have to be pessimistic about a mindset like that. Why? Because it will diminish naturally, when the process of maturation has impacted our way of thinking.

This is a natural law applicable to Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

Source: By Abdurrahman Wahid (aka Gus Dur), in Tempo Magazine, June 20, 1981

Mengapa Mereka Marah?

Oleh Abdurrahman Wahid (Majalah Tempo-20 Juni 1981)

Seorang kawan menanyakan, mengapa banyak pemuka agama Islam marah kalau mendengar sebutan ‘kaum fundamentalis’, atau tersinggung kalau ada yang membicarakan ‘issue negara Islam’.

Pertanyaan yang patut direnungkan, karena ia menunjuk pada perkembangan sangat kompleks dalam kehidupan bermasyarakat kaum muslimin. Juga bersangkutan dengan kemelut identitas kultural muslimin di seluruh penjuru dunia tidak hanya di negeri kita.

Pertanyaan kompleks sudah tentu tidak dapat dijawab sederhana. Membutuhkan renungan yang dalam, juga tidak kurang keberanian moral untuk melihat masalahnya dengan jernih. Dengan tidak hanyut oleh luapan marah, atau ketakutan yang disembunyikan rapat-rapat di balik kebanggaan akan peranan kesejarahan diri sendiri, atau kegairahan menudingkan jari terhadap kesalahan ‘pihak lain’ dalam percaturan politik, kultural dan keagamaan yang dihadapi.

Juga memerlukan kesanggupan untuk menelusuri mana wilayah kehidupan yang hakekatnya menjadi ‘agenda pemikiran’ kaum muslimin, dan membedakannya dari agenda semu yang kini dijajakan sebagai pertanda kebangunan kembali Islam.

Pengagungan Diri

Kaum muslimin di mana-mana terbagi dalam dua kelompok utama: mereka yang mengidealisir Islam sebagai alternatif satu-satunya terhadap segala macam isme dan ideologi, dan mereka yang menerima dunia ini ‘secara apa adanya’.

Pihak pertama menganggap Islam telah memiliki kelengkapan cukup untuk menjawab masalah-masalah utama umat manusia. Tinggal dilaksanakan ajarannya dengan tuntas, tak perlu lagi menimba dari yang lain. Karenanya, kalau dianggap perlu ada dialog dengan keyakinan, isme atau ideologi lain, haruslah ia diselenggarakan dalam kerangka menunjukkan kelebihan Islam.

Seonggok ‘pembuktian’ diajukan—umumnya dengan mengemukakan jawaban idealistis yang pernah dirumuskan Islam. Sudah tentu jawaban itu dilandaskan pada sejumlah pengandaian serba idealistis pula: kalau saja umat manusia mau mengikuti ajaran Islam (padahal kenyataannya tidak), jika para pemimpin menggunakan moralitas Islam (padahal hanya satu dia orang saja mampu), dan seterusnya.

Postulat-postulat formal Islam diajukan sebagai jawaban terhadap kemelut kehidupan masa modern: ayat-ayat Qur’an dan hadith Nabi sebagai tolak ukur lahiriah satu-satunya bagi ‘kadar keislaman’ segala sesuatu uang dikerjakan.

Tidak heran kalau sikap kritis terhadap diri sendiri tidak dapat dikembangkan sepenuhnya—terhalang oleh ‘sudah sempurnanya’ Islam sendiri. Lalu menjadi wajar juga kecenderungan untuk hanya mampu mengagungkan diri sendiri, yang memandang remeh perkembangan. Perkembangan apapun di luar keasyikan kita dengan kehebatan Islam lalu tidak memiliki nilai yang tinggi.

Kalau perkembangan di luar tidak dapat diabagikan, dicarilah alasan untuk menghindarkan pemikiran mendalam atasnya: ini buah pikir komunistis, itu ide sekuler, dan seterusnya. Semakin besar kenyataan di luar menghadang ufuk pandangan kita, semakin hebat upaya melarikan diri dari perwujudan kongkritnya.

Kalau diajukan pemikiran untuk mencari jawaban kongkrit (bukan hanya idealistis) dengan jalan menghadapkan ajaran Islam pada kerangka berpikir baru yang bersumber pada isme, keyakinan dan ideologi lain, maka cap kemurtadan, kekafiran dan (lagi-lagi) sekuler dipakaikan pada usul itu sendiri.

Mental Banteng

Timbullah apa yang kemudian dinamai sejumlah pengamat sebagai ‘mengal banteng’: Islam harus pagari rapat-rapat dari kemungkinan penyusupan gagasan yang akan merusak kemurniannya. Tanpa disadari, mental seperti itu justru pengakuan terselubung akan kelemahan Islam. Bukankah ketertutupan hanya membuktikan ketidakmampuan melestarikan keberadaan diri dalam keterbukaan? Bukankah isolasi justru menjadi petunjuk kelemahan dalam pergaulan?

Kalau kepada sikap jiwa seperti itu diajukan tuduhan oleh pihak luar akan adanya fundamentalisme, atau tentang masih adanya pemikiran mendirikan ‘negara Islam’, jelas rasa marah yang muncul sebagai reaksi. Bukankah karena ketakutannya terhadap ‘pengaruh negatif’ luar, ia lalu curiga terhadap semua pendapat ‘orang luar’ tentang dirinya? Bukankah kepekaan adalah hasil dari sikap mengunci pintu seperti itu?

Padahal penamaan sebagai kaum fundamentalis tidak ditukulan kepada semua muslim yang mengidealisir Islam dan menempatkannya sebagai alternatif tunggal bagi semua isme, keyakinan dan ideologi yang ada. Cukup besar jumlah idealis muslimin yang mampu menerima kehadiran isme-isme lain dan melihat peranan agama mereka dalam fungsi mengarahkan isme-isme itu bagi kebutuhan hakiki umat manusia, entah nasionalisme, sosialisme dan seterusnya.

Banyak sekali idealis muslimin yang melihat ideologi formal negara sebagai pengatur pergaulan politik, sedang Islam difungsikan terutama dalam pergaulan sosio-kultural. Jelas tidak semua kaum idealis muslimin fundamentalis. Kalau demikian, mengapa hampir semua ‘idealis muslim’ marah terhadap istilah di atas, atau terhadap anggapan masih adanya aspirasi mendirikan ‘negara Islam’ dan sebangsanya?

Karena mereka mengurung diri dalam benteng mental yang mereka dirikan. Semua penamaan ‘dari luar’ lalu dianggap mengenai semua warga benteng, sebagai tuduhan serampangan dan prasangka buruk terhadap semua muslimin idealis yang berada dalam benteng. Simplifikasi permasalahan adalah metode pemikiran mereka, sehingga pemberian nama apapun yang dirasakan tidak simpatik dianggap ancaman.

Memang jauh implikasinya bagi masa depan perkembangan Islam. Tapi sebenarnya kita tidak usah pesimistis dengan sikap jiwa seperti itu. Mengapa? Karena itu akan berkurang dengan sendirinya, kalau proses pendewasaan telah mempengaruhi cara berpikir.

Ini hukum alam. Berlaku baik untuk muslimin maupun yang bukan.

Footnotes:

- Abdurrahman Wahid, commonly known as Gus Dur, was born on September 4, 1940, in Jombang, Indonesia. He was the fourth president of Indonesia, serving from 1999 to 2001. A respected Islamic scholar and leader, he was the chairman of the Nahdlatul Ulama, one of Indonesia’s largest Muslim organizations. As a moderate and inclusive figure, Wahid promoted interfaith dialogue and played a pivotal role in fostering religious harmony in Indonesia. Despite health challenges, his presidency focused on political reform and decentralization. His commitment to democracy and religious tolerance left a lasting legacy, and he is remembered as a prominent figure in Indonesian and global politics. Abdurrahman Wahid passed away in 2009. ↩︎

- 1980s Tension in MUI Leadership: The Indonesian Ulema Council (Majelis Ulama Indonesia or MUI) experienced internal divisions during the early 1980s. The leadership controversy within MUI was accompanied by accusations of ‘fundamentalism.’ Different factions labeled each other as ‘fundamentalists’ in an attempt to discredit their rivals’ legitimacy and claim to represent mainstream Islamic thought. This controversy highlighted the political struggle for influence within the religious establishment.

Political Opposition Accusations: In the early 1980s, opposition groups accused the government of employing ‘dirty tricks’ by labeling them as ‘fundamentalists’ to undermine their credibility and political influence. This was particularly common during elections, where opposition candidates or parties who were perceived as posing a threat to the ruling regime were stigmatized as radical or extremist, using ‘fundamentalist’ as a pejorative term. For example, during the early 1980s, a notable example of political opponents being labeled as ‘fundamentalists’ occurred in the lead-up to the 1982 Indonesian legislative election. In this election, the Indonesian Democratic Party (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia or PDI), led by Megawati Sukarnoputri, was perceived as a potential threat to the ruling government of President Soeharto. As the election neared, certain elements within the government and the ruling Golkar party sought to undermine the PDI’s credibility by accusing it of having ‘fundamentalist’ ties. These allegations were aimed at tarnishing the PDI’s image and portraying it as a party with radical or extreme Islamic affiliations, despite the party’s diverse and moderate platform.

This ‘dirty trick’ tactic was intended to weaken the PDI’s electoral prospects and ensure the continued dominance of the ruling Golkar party. Although it is important to note that Megawati Sukarnoputri was not known for advocating Islamic fundamentalism, the political climate at the time involved the use of such tactics to discredit opponents. The 1982 legislative election took place under these politically charged circumstances.

Political Agendas vs. Religious Identity: Some political controversies arose when politicians attempted to exploit religious sentiments for their own gain. In the early 1980s, there were allegations that certain political figures used religious issues and labeled their opponents as ‘fundamentalists’ to manipulate public opinion. This tactic was a ‘dirty trick’ aimed at discrediting opponents by linking them with extremism and potentially damaging their reputations in a predominantly moderate and pluralistic society. ↩︎ - The issue of groups attempting to establish an “Islamic state” in Indonesia has deep historical roots, with examples dating back to the 1940s and 1950s. During this period, movements aimed at creating an Islamic state emerged, most notably the Darul Islam movement. The 1940s saw the rise of the Darul Islam movement, led by Kartosuwirjo, which aimed to establish an Islamic state in parts of Indonesia, particularly in West Java and South Sulawesi. This marked a significant shift towards more radical and separatist goals, with the group resorting to armed conflict to achieve its objectives. However, the Indonesian government, led by President Sukarno and later President Suharto, took firm measures to suppress the movement, and by the 1950s, it had largely been quelled. Fast forward to the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period marked by the Iranian Revolution of 1979, which resulted in the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The success of the Iranian Revolution had a profound impact on Islamist movements worldwide, including in Indonesia. Inspired by the Iranian model, Indonesian Islamist groups, such as the Indonesian Mujahideen Council (Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia or MMI), began advocating for the establishment of an Islamic state based on Sharia law.

Indonesia’s response to these movements has involved a combination of measures. The global “war on terror” in the post-9/11 era has also played a role in influencing Indonesia’s domestic strategies, aligning them with international pressures to combat extremism and terrorism. ↩︎

Leave a Reply