The Translator’s Death

A Short Story by Wawan Kurniawan

c.1847

He would not have swallowed the poison had yesterday’s occurrence not come to pass. A week prior, in the realm of dreams, a woman clad in crimson, her tresses falling to her shoulders, approached him upon the shore of some strange and unfamiliar sea. Ere he might glimpse her countenance, she clasped him from behind—so fierce was her embrace, he feared his bones should crumble within him.

When the crackling of ribs and the searing of pain overwhelmed his senses, he awoke.

The clock upon the wall marked the hour—three and forty-two minutes past. Naught but the ticking of its hands disturbed the solitude. He resolved to close his eyes once more, banishing all memory of the vision. Yet the ache upon his back lingered, forcing him to shift time and again upon his couch.

At last, slumber reclaimed him, and he woke at the hour of ten. Ordinarily, his days began far later, his nights squandered upon the ceaseless toil of translation, his manuscript forever aglow with unfinished pages. Yet the pain, dull and insistent, roused him early, though his sleep had already been troubled. He pondered its cause.

“Perchance my posture was ill-kept in slumber.”

“Nay, it is the hours I spend hunched over my work.”

“No—it must be that I drank too little yesternight.”

Of all these musings, never once did the dream alight in his mind.

As he wrestled with his discomfort, remembrance of his promise to Eka surfaced—Eka, the master of the press that sought to print his translation. Twice had he begged for more time, eager to refine his work, and now but six days remained ere the final hour struck. He dared not seek another extension, yet neither could he declare his labors complete.

Suppressing his agony, he hobbled to the bath, his fingers groping the cold walls for support. His gait was that of an old man bereft of his staff—one hand pressed to the stone, the other massaging his own wretched spine.

“What curse is this? Why dost Thou afflict me so, O Lord?” he lamented.

The house stood empty. Once, a feline companion had shared his solitude—a creature he named March, in honor both of his birth and of those authors he held dear. But the distance between him and the washroom now yawned like a yawning chasm.

Retreating, he sank into the embrace of a brown armchair, its soft depths granting some respite. Drawing a deep breath, he sought a position less wretched than the last, and his suffering momentarily eased.

A book lay at hand upon a small wooden table to his side. There, too, rested a thin, white-covered notebook, bereft of any adornment, and two pens, oft wielded either for his notes, or to banish his unrest, their tips drumming endlessly against the wood. He seized the book—one hundred and twenty-three pages remained to be conquered. With each leaf turned, the burden upon his back grew lighter. He surrendered himself to the comfort of his chair, his limbs lulled into calm repose.

And yet—an urgent call from within. The need to relieve himself pressed sharply, but he, loath to stir from his fragile sanctuary, resisted. The sun, hindered by a curtained window, cast but a pale glow upon the room. Still, a warmth, at once humiliating and soothing, seeped betwixt his thighs, and he shut his eyes, surrendering to the sensation.

Not until the final page was turned did he rise from his seat.

***

Having revisited his translation, he collapsed upon the floor. That very noon, upon consulting William—a physician, and friend—he had been bid avoid his bed. Sleep eluded him still, but the pain, insidious and unrelenting, left him no choice. Only upon the hard boards did his torment abate. Yet before succumbing to rest, he sought again the voice of Nadira, his betrothed.

Two days past, Nadira had returned to Selayar, where she prepared for their union, set for midyear. But she answered him not—neither voice nor written word came from her.

On the eve of her departure, the storms in Selayar had grown fierce. The winds raged, and the sea, dark and roiling, devoured all sound. The day before, she had written, warning that the tempest had worsened, that they might not speak again for some time.

He scoured the news, seeking news of Selayar. The waves battered the land, the gales unceasing. And still, silence from Nadira. Unease took hold in his breast, dread curling around his ribs like a specter’s grip. The pain of his body faded in the wake of a far graver affliction—the uncertainty, the gnawing fear. He reread their past exchanges, clinging to her words. He smiled. He laughed, alone in the empty night. And then, unaware, sleep stole him away, his hand clutching the lifeless phone.

Once more, the dream unfurled before him. Night after night, for five nights hence, the vision tormented him. At last, the veil lifted, and the memory of it burned clear within his mind. He could recall all—save the face of the woman, save the shore upon which they stood.

That night, he reached for Nadira, his fingers trembling upon the screen. He told her of the dreams, the terror that gnawed at his soul. Yet the dread within his chest refused to be quelled. He turned again to the news, but no further word came from Selayar—the storm had swallowed even the voices of the journalists.

The agony in his back, now creeping, took hold within his tailbone. His limbs failed him. He lay upon the floor, staring at the dim glow of his chamber’s light. The bulb flickered—then died. A chill gripped him, his body frozen in time. He could not move, could not scream.

And then—the light returned. And she was there once more.

The woman in red, the long-haired specter of his nightmares. But now—now, he saw her face.

Nadira.

His breath shuddered, not in terror, but in cruel confirmation. The dread that had haunted him these past days now showed its fangs. Something had happened. Something beyond the storm. Something final.

Her image melted, vanishing in a whisper of air. His body, freed from its eerie paralysis, convulsed with pain. He rose, trembling, his tailbone a searing wound.

The manuscript stood open, the translation incomplete. No word from Nadira. His anguish mounted—despair, thick as the night, smothered him. A whisper curled through his mind—a voice, urgent, unrelenting. The kitchen. The bottle. The poison.

The woman he beheld—she was Nadira. And Death had claimed her first. He, who had spent his life translating words, could not translate this terrible truth.

He staggered forward, reaching for the fatal vial. And as his fingers grazed its glass surface—I embraced him. I held him, as I had held Nadira before him, as the waves had clasped her beneath the storm. Why, oh why, had he not translated me first?

The Translator’s Death is an unauthorized experimental version of Wawan Kurniawan’s short story Kematian Seorang Penerjemah, published in the national daily newspaper Kompas on 24 March 2019. (Accessed 24 March 2025 from https://ruangsastra.com/4307/kematian-seorang-penerjemah/.)

Wawan Kurniawan, writes poetry, short stories, essays, novels, and translations. Joined the Kompas Daily short story writing class (2015), published a book of poetry entitled Persinggahan Perangai Sepi (2013) and Sajak Penghuni Surga (2017). One of his novels entitled Seratus Tahun Kebisuan (A Hundred Years of Silence) is a Unnes International Novel Writing Contest 2017 Novel of Choice. Check out https://www.instagram.com/wawankurn/

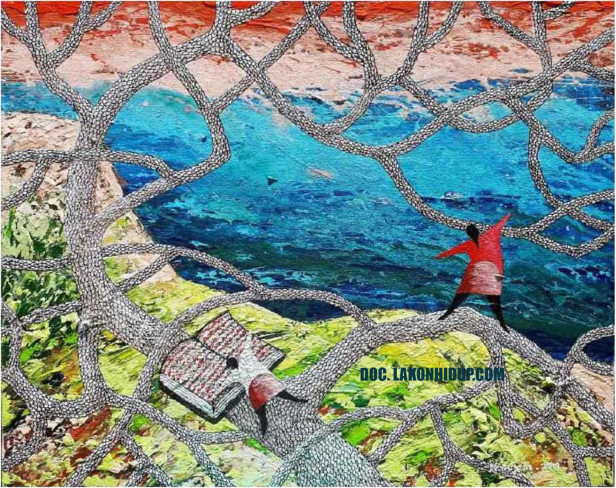

Nyoman Sujana Kenyem, born in Ubud, Bali, 9 September 1972, Nyoman studied at STSI Denpasar (1992-1998). His solo exhibitions include A Place Behind The House at Komaneka Gallery Ubud, Bali (2016), Silence of Nature, at Lovina, Bali (2015), and his solo exhibition at G13 Gallery, Kelana Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia (2013). See https://www.instagram.com/artkenyem/

Leave a Reply