The Man Who Hired Himself Out

A Short Story by Pramoedya Ananta Toer

I was four years old. Or at least, that’s what I remember. And I had known that family for a long time: Leman’s Grandpa and Grandma, Leman, Siah, Nyamidin, and Sidin.

If I visited their house at nine in the morning, they would still be home. They hadn’t started work yet. I’d tug at Grandpa Leman’s leg. He understood, and gave me the last of his coffee. I laughed. He laughed. Grandma Leman laughed. And when I asked, “Where’s Siah, Grandpa?” he would always answer, “Still asleep.”

“But I’m already awake.”

He always laughed at how proud I was of myself.

“Siah is a lazy kid,” he’d often say, never wanting to hurt my feelings.

“Where’s Leman, Grandma?”

“At the river — bathing.”

“Nyamidin, Grandpa?”

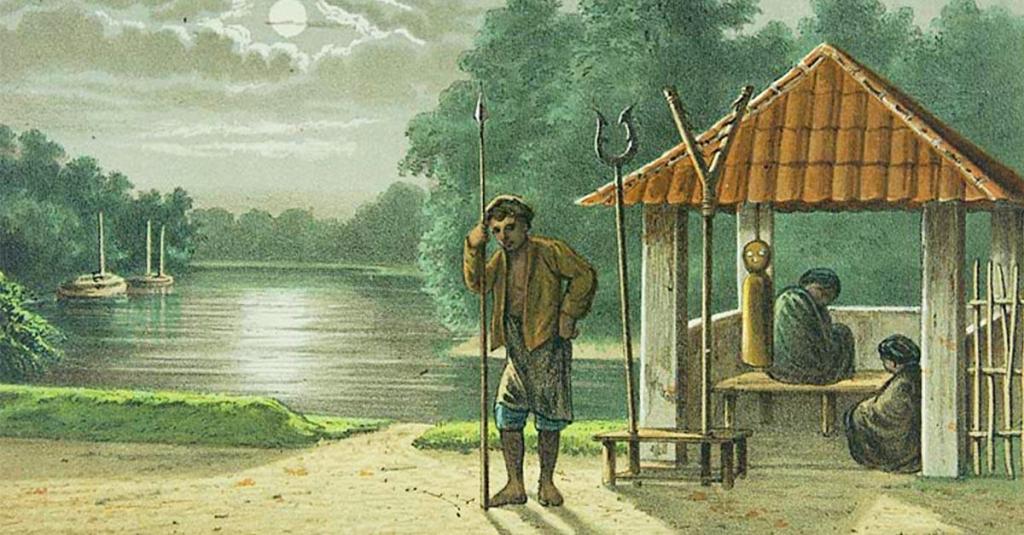

“He hasn’t come home yet. He was guarding the watch post last night. Have you seen the post near the cemetery? He sleeps there.”

“Not awake yet?”

“Probably not. He’s tired from patrolling all night.”

Sometimes, they’d give me some boiled sweet potatoes or cassava. When there wasn’t anything fun left to do, I’d run back home. I’d tell Mama about my little adventures. Almost without fail, she’d raise her finger in front of my nose. Her slightly almond eyes fixed on me. She’d say, “I’ve told you many times. You shouldn’t go there. You’re bothering them when they’re working.”

“They aren’t working.”

“They don’t work because you’re there.”

“But Siah was still asleep. The others were still asleep too.”

“That’s why you shouldn’t go there,” her finger lowered and rested in her lap. Her voice, usually firm, softened, “Laziness is a disease, like an eye infection. It can spread. If you keep going there, you’ll catch their laziness.”

I’d never heard advice like that before. And I went back again when the sun was high in the sky. I told Grandpa Leman what Mama said about laziness spreading. He calmly and honestly replied, “I am a lazy person. If I was hardworking, what would I do?” He laughed softly through his nose. “I have no rice field. No garden. Not even a hoe. I only have a machete. Every day I sharpen it.” His eyes glanced at the sharpening stone, worn deep at the center, clean and almost shiny. “If someone asks me to take over their night watch, I get two and a half cents. If I didn’t have such a sharp machete, no one would ask me to fill in for them.”

His voice had a sad music to it. I liked listening to him.

“Say it again,” I’d ask.

Grandpa Leman almost never refused my requests. He’d repeat his words slowly. Even though I didn’t fully understand all of his sentences, I could memorize them. At home, when Mama wasn’t around, I’d often repeat the old man’s words to myself. The sad music lingered, even when I spoke them.

One day, Mama said to me, “Every lazy person loves to eat,” and then, “a personality that makes trouble for everyone.” Since then, I never repeated Grandpa Leman’s words. I didn’t know why. But I felt a challenge in Mama’s words, like they were directed at me, and at Grandpa Leman.

Then, for a long time, I didn’t visit the Leman family home, until one day I went back. I asked, “Where’s Siah?”

Grandpa Leman lowered his face. Grandma Leman cleared her throat softly. Neither of them answered. Every time I visited, I’d ask. But one day, Grandpa Leman said, “Siah went — went to Palembang.”

“Is Palembang far, Grandpa?”

“Far. Across the sea. You take a ship to get there.”

“What’s she doing there, Grandma?”

“Making a living. When she comes back, she’ll bring gold coins,” Grandma Leman answered. Her face showing a look of self-mockery.

“Times are harder now,” Grandpa said, without being asked. “A lot of gentlemen have lost their positions.”

I memorized his words one by one, eager to tell Mama or Papa. I felt restless until I could deliver the news. One afternoon, while Papa was sitting on the garden bench, I went up to him, almost blurting out the news from Grandpa Leman.

But Papa spoke first: “You used to ask to go to school. Why don’t you ask anymore?” I jumped up with happily.

“Of course, I still want to go,” I hollered. “When am I going to start, Papa?”

“Tomorrow.”

The new news made me forget the news I had got from Grandpa Leman. The next day was my first day as a student—at the age of four. Now I realized how school really stole away the coffee I used to get from Grandpa Leman. Except on holidays or weekends, I had no chance to wander in the morning. At school, I made a lot of new friends, heard new stories from around the city, and saw scenes that changed every day.

When I arrived home from school, sometimes Grandpa Leman would be waiting for me in front of his house and give me a new kite that he’d made. But strangely, I could never make the kite fly, not even just for a moment. Unlike other children. Eventually, those kites became the target of my frustration. I tore them up. Broke them to pieces.

I think it was not less than six months that I didn’t visit Grandpa Leman’s house. Until that time arrived, the long holiday. With the arrival of the holidays, Mama’s ban on playing to my heart’s content was lifted.

One day during the holidays, while I was playing with my friends in the middle of the road, a horse cart pulled up out front of Grandpa Leman’s house. Without being told, all the children ran into Grandpa Leman’s house to look for new stories and maybe some snacks.

I saw Siah sitting on the bench beside a middle-aged man wearing black clothes. She was looking down. Siah smiled when she saw me, stood up from the bench, and came over.

“It’s been a long time. I missed you.” She laughed.

I saw she had two gold teeth. The seven safety pins of her kebaya were made of plate gold and connected by a gold chain.

“So now you’re rich, are you?” I asked.

In response, she gave me a sincere kiss.

“Can I have one of those pins?” I asked.

She shook her head gently. With a coaxing voice, she said, “When you grow up, you can get one yourself.” After saying that, she gave me some snacks that she’d brought.

Grandpa Leman was politely chatting with the man who also had gold teeth like Siah. I was amazed at how polite Grandpa could be. Grandma Leman was bustling in the kitchen boiling water.

Since Siah had arrived, I started to visit this house often again. Her stories about elephants, tigers, cheap people, and cheap gold fascinated me. She taught me to mimic the sounds of wild animals. At home, I retold the stories I had heard. At school, I spread all the news. And after sharing the stories, I felt relieved inside.

After the holidays, I would visit after school. More often than not, I found Siah still asleep in the afternoon. Until one day, I noticed the man with the gold teeth was no longer at Grandpa Leman’s house.

“Where is he, Grandpa?” I asked.

“Gone,” he replied unhappy.

“Where to?”

“Don’t know.”

“Siah?”

“Not back yet.”

“Did she go with him?” I asked eagerly.

He shook his head heavily.

“Will she come back, Grandpa?”

Grandma Leman appeared from the kitchen and answered, “I hope she never comes back. I hope she dies sea.”

“Which sea, Grandma?”

“The sea there over the ocean,” she replied, annoyed.

I thought, maybe Siah went to Palembang again. But I didn’t ask. I could see that the faces of the old couple were unhappy.

“I haven’t seen Leman in a long time. Where is he, Grandpa?”

Grandpa Leman sighed deeply.

He told a sad tale. “A lot of gentlemen have lost their positions now. They can’t call Leman and order him to fix the fence or the toilet anymore. If he replaces someone on guard duty, I don’t get paid. I am getting on now. So the turn to take the guard duty pay has been given to me. He went somewhere else to make a living.”

“Where, Grandpa?”

“Cimahi — he enlisted to become a soldier.”

“When he comes back, he’ll be wearing green, won’t he, Grandpa?”

“I don’t think he’ll be coming back. I don’t think he’ll remember his grandpa and grandma anymore. I think…”

“In the past, a lot of soldiers never returned,” interrupted Grandma. “The retired constable said the war in Aceh is over. Soldiers don’t have any work now, all they do is practise drills and shooting.”

I remembered the lines of police that marched every Wednesday and Saturday to the shooting range across the river. They looked so gallant, with their big bodies and rifles swinging on their backs.

“What about Nyamidin, Grandpa?”

“Now the landowners work their own fields. Money is scarce. So, he left, who knows where. No one makes wooden toys for you anymore,” he said.

“Wasn’t he happy here?”

“If anyone has some money, they’d be happy wherever they are. It’s different if you have none, and money is hard to come by.” He coughed for some reason. “It’s better not to ask anymore,” he said, lowering his head—lower and lower until it almost touched the table. His gray hair, black and white mixing, covered his face. I left, and he didn’t notice.

Of course, I told all of this to Mama and Papa. Although they were really paying close attention, they pretended not to be listening. I didn’t know why. But it didn’t make me happy.

“Have you taken a bath?” Papa asked, cutting off my news.

The question was enough to force me to the bathroom. As I washed, I looked at the walls. Suddenly, I thought, “This bathroom is much better than Grandpa Leman’s house.”

After bathing, I asked Papa, “Why is our bathroom better than Grandpa Leman’s house?”

Papa appeared to think hard. But when he answered, it was with a strange, hollow laugh. And I didn’t understand. I saw Mama suddenly deep in thought. I asked her, “Why is our bathroom better, Ma?”

She was still frowning. And when the frown disappeared, she looked at me and said, “Are you able to read now?” A question I hated.

I stood in silence. Confused. Mama got up from her seat, took my hand, and led me to the porch. Learn! And then, my ear was red from her hand. After my tears had dried, she issued a warning: “Now you can’t go there anymore. If you do…” a threat I had never heard before, “I’ll smack you with the broomstick.”

And since then, I did not go there again.

A year passed. But I was still in first grade. My body grew as slowly as my intelligence. In every game, I was still considered a hanger-on—just tagging along without full rights. One day, I played hide and seek with the other children. We hid behind Grandpa Leman’s house. Unexpectedly, I heard a man’s voice I had never heard before: “Do you want to, or not?” the man’s voice urged.

“I wouldn’t dare, sir. It’s true we are poor, but we are respectable people.”

“Five rupiah?”

“I wouldn’t dare, sir.”

“Six rupiah.”

“Seven,” the man said, “I see your machete is so sharp. One slash, and your work is done.”

“Seven and a half,” and the urging continued. “Ten rupiah, then. I can’t go any higher.”

I didn’t pay much attention to the voices. When we crawled out from hiding, I saw a gentleman coming out of Grandpa Leman’s house. He wore fine batik, shiny sandals, a Solo headdress, and a buttoned shirt with silver buttons. That too didn’t catch my attention. Two or three days later, I saw the man again. But still, my attention wasn’t roused.

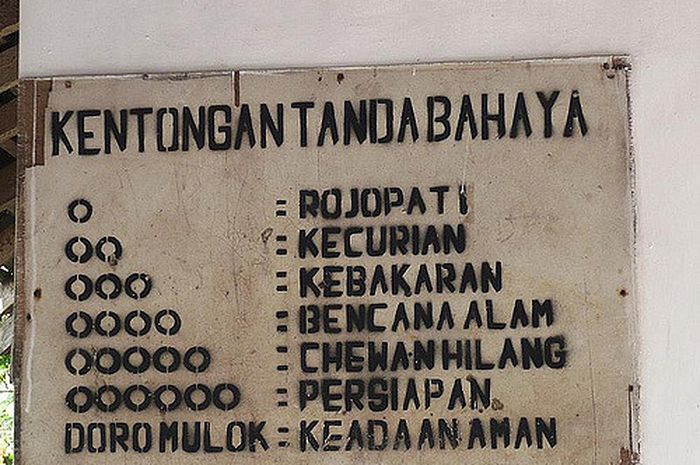

Then that night arrived. A night I will never forget. Papa and Mama were sitting on the porch with me and my little sibling. The moon was shining brightly. But suddenly clouds moved over the moon. There was darkness. Thunder started to rumble. Sometimes faint, sometimes louder. Lightning flashed now and then. We went inside to eat dinner. Outside there was the sound of the wooden guard-post warning drums, calling to each other in the distance.

“Which drum started first just now?” Mama asked.

“The one from the village here,” Papa replied.

We sat listening in silence.

“Quick continuous drumming. That means murder,” Papa said, rising from his seat. “Stay inside. I’ll be back in a while.”

Mama looked nervous. I didn’t understand what was happening. I asked her again and again, but she didn’t answer. Her eyes darted around the room, moving from one dark corner to another. The oil lamp in the middle of the table glowed peacefully. My little sibling had been asleep since seven.

A quarter-hour later, Papa returned, face tense.

“What happened?” Mama asked anxiously.

“Ah, old man Leman,” Papa replied as he sat down. “Luckily, he only used a mallet. The one he attacked was able to make it to the village hall.”

“Was it really old man Leman?” Mama asked. Papa nodded.

“What did he do to them?”

“He beat him. But thank goodness he didn’t use his machete.”

“Why did he use the mallet?” Mama asked.

“When questioned, he said, ‘My machete, sir, is the only thing that earns me a living. I can’t use that to do something wrong. So I used the mallet.’”

“What’s wrong, pa?” I ask. But papa didn’t pay any attention.

“I can’t believe the old man could do such a thing,” Mama said.

“Anything is possible. Not everyone is always in their right mind.”

We ate in silence, but the incident with old man Leman stayed on my mind. That night, the whole town felt uneasy, a feeling that seeped into the hearts of its residents.

The next morning, the news of the previous night’s attempted murder spread everywhere. Since then, old man Leman was no longer seen at his house.

People said he was locked up in prison. Every morning, I waited, hoping to see him among the prisoners hauling night soil to the river. But he never appeared. And I went to school with memories of him.

Three months later, news spread: old man Leman was sentenced to seven months hard labor in city of Malang. At home, Papa said to Mama, “You were right. He wasn’t evil. He got ten rupiah for the job from someone.”

I tried to warn them about the pressure of the gentleman who went to Grandpa Leman’s house, but they didn’t listen to my story. I had to keep it to myself. A story that raged inside me. That I needed to tell someone to ease my heart.

The news that old man Leman had tried to kill someone deeply shook what I thought about him. My memories of him often made me scared at night.

Before the old man returned home again something startling happened.

That evening, we were playing ball in the middle of the road. From a distance, I saw a figure walking with difficulty, dressed entirely in black. But the figure couldn’t distract us from our game. So, I was shocked when suddenly, the figure was standing in front of me. The bent-over figure! Up close, I saw he was shabby, hunched, supported by a stick. The mouth smiled at me. “Don’t you remember me?”

I saw the gold teeth. Siah! The memory reminded me of old man Leman. I screamed and ran home, looking back three or four times to see Siah still standing there, hunched over, watching me.

I didn’t tell anyone about my encounter that evening, even though I desperately wanted to share it. That night, I couldn’t concentrate on studying. Mama’s tugs on my ear and pinches didn’t help me focus on my lessons.

“Why are you getting dumber!” Mama shouted in frustration.

She dragged me to the bathroom, washed my feet, carried me to bed, and threw me onto it. Her voice was soothing now, “Why are you so stupid?”

But the image of Siah and the memories of old man Leman was all I could think of, more than my fear of Mama’s pinches and tugs. When I saw Mama looking sad, I finally had the courage to say, “I’m scared, Ma.”

“Of what?”

“Siah came and talked to me. I’m afraid old man Leman will attack me with a mallet me.”

Mama stroked my forehead and hair. She spoke gently, “It’s okay. Go to sleep.”

“I’m scared.”

“Do you want to sleep with me?”

I nodded. That night, I slept safely in her embrace.

The next morning, I heard that Siah’s gold jewelry had all gone. Only the gold in her teeth remained. Once, I saw her walking to the river to bathe, but she didn’t walk as she used to. It seemed as if there was an invisible cushion between her legs. Everywhere she went, she always wore the same black clothes.

“Why doesn’t Sidin ever visit his parents, Ma?” I asked Mama when the news about Siah was spreading.

“Sidin works hard. He’s bought a house now. Of course, he wouldn’t want to bother with lazy people. I don’t like working for lazy people either. And if you’re lazy, I won’t cook for you.”

Those words were tough enough for me to shut my mouth.

Time passed, day turned to day. Now, Grandma Leman was often seen leaving the house. Everyone knew she wandered to neighbors’ houses around mealtime. Siah rarely appeared except when she went down to the river to wash.

Once, as she was having lunch, Mama said to Papa, “Grandma Leman came here earlier.”

“Did you give her advice?” Papa asked.

“Yes.”

“Giving her advice is worthless. Just give her money or food and send her on her way. Not one person can hide her laziness.”

I didn’t dare contribute to the conversation.

Eventually, the seven months passed.

Grandpa Leman returned home again. He never left the house. Every day he worked hard making baskets and other goods from coconut fiber. He did not socialized with anyone any more. When people invited him to community meals, he would come, but he wouldn’t talk. As soon as the meal was over, he would leave quietly.

Once a week, he took his handmade goods to the market. Grandma Leman no longer wandered around at mealtime.

Sometimes I saw Grandpa Leman weaving outside the house. When he saw me, he wouldn’t greet me, and just continued his work. And when he returned to his task, not a single black hair remained — it was completely white.

Jakarta, 9-1951.

Toer, Pramoedya Ananta. (1994). The Man Who Hired Himself [Yang Menyewakan Diri]. From Cerita dari Blora: Kumpulan Cerita Pendek [Stories From Blora: Collection of Short Stories] (pp. 1 to 26). Jakarta: Hasta Mitra, 1994. https://archive.org/details/ceritadariblora.

Featured image credit: Lithograph of a night watchman at a riverside patrol post in a Dutch East Indies village at the end of the 19th century. (www.geheugeonvannederland.nl) https://historia.id/urban/articles/melihat-indonesia-melalui-pos-ronda-Dnow4/page/1

Leave a Reply